The holy month of Ramadan started early for Muslims in Gaza this year. In some sense, we’ve been fasting since October. But for tragic reasons.

Ramadan has a special place in every Muslim’s heart. We wait for it all year. As a small child, I remember my excitement at hanging colorful lanterns on the house. My parents taught my siblings and me to abstain from food and drink from dawn to dusk, instilling in us that the idea of fasting is to train yourself to be patient, to elevate your soul from mundane desires, and to try to free your mind from evil impulses, and do good deeds for people around us.

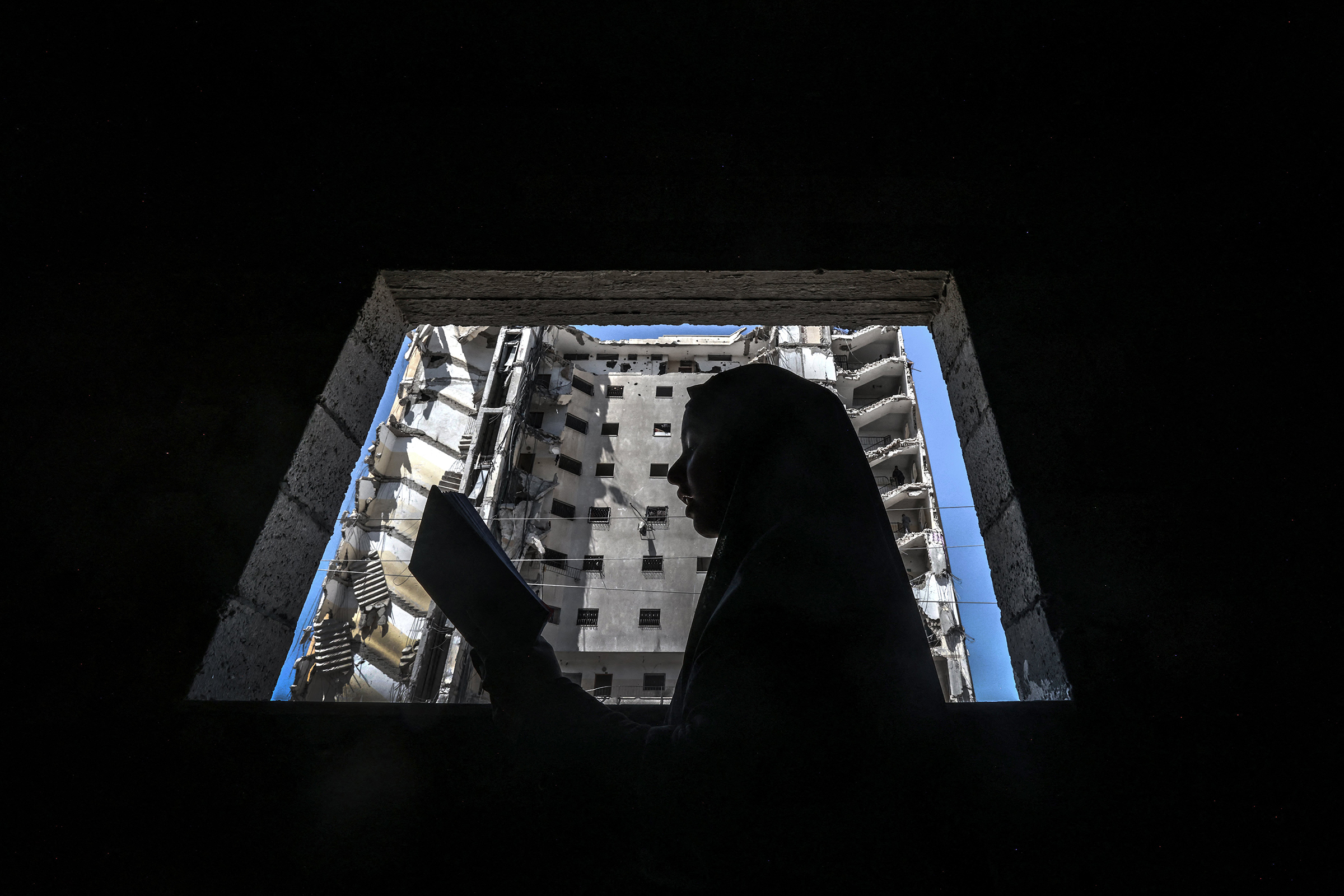

Nothing could have prepared me for Ramadan this year. I wasn’t sure I would even survive until Ramadan—at least 30,000 Palestinians in Gaza have been killed since Oct. 7, and 80% of the population has been displaced. For those of us lucky to still be alive, fleeing from place to place, we have undergone a partial fast for months, not wanting to eat the scant food of the families kind enough to shelter us, unable to find food to purchase in the markets, or to afford what can be found.

Since Ramadan last year, my life has been turned upside down. My home in Gaza City, where my children and I used to hang Ramadan lights, is now destroyed and my family scattered.

I woke Monday, the first day of fasting, an hour before dawn to prepare the pre-fast meal known as suhour. This is usually a moment of profound joy and spirituality but this year I could not hold back my tears. The mosques lie in ruins, so neighbors all around performed the call to prayer on their own initiative. Suhour consisted of stone-hard bread, which I baked from barley, corn, soy, and even bird feed that we managed to find and ground together. The sand-like taste was tempered by the fact that we were able to dip it in the olive oil that we pressed from our own olive trees before the war, which I found in my father’s deserted home in Gaza City. It pained me to not be able to offer food from a plentiful table to our neighbors, as is customary, and instructed by the Prophet Muhammad.

Read More: A Photographer Captures Death, Destruction, and Grief in Gaza

For our first meal after fasting, I had saved two small bags of pasta. Though it was infested with weevils, I managed to clean and boil the pasta, and serve it with tomato sauce for iftar. I used to partially prepare the next day’s iftar the night before, so that my fasting hours could be focused on worship. With so much scarcity, this is now a faraway dream.

In years past, after iftar, we would pray in the mosque and then visit our close relatives, sharing qatayef, a fried Ramadan dessert drenched in syrup. These visits would present an opportunity to forgive those who may have wronged us, strengthening our social fabric. With so many mosques destroyed, and no qatayef amid a dearth of food and essential items, I cannot celebrate with my parents, siblings, and their spouses and children. There are 20 of them all crammed into a one-bedroom apartment in Nuseirat in central Gaza.

Instead, my family and the friends we are staying with, prayed together, 16 of us packed into the small apartment in Gaza City. All of us keenly feel the absence of friends and family seeking refuge elsewhere. Though many of them are less than 10 mi. away, we are separated by Israeli tanks and soldiers who make the journey impossible, or too dangerous to attempt. But we also have extended family members killed by Israeli airstrikes, tanks, or snipers.

Yesterday, my 18-year-old daughter Rana had a crying fit. When she finally calmed down, she asked, “Mom, for how long do we have to live in this nightmare? I want to go home. I want to sleep in my bed and have my things around me.” Rana has been strong throughout, telling jokes to lift our spirits and keep us calm through the bombardments. But starting a Ramadan filled with violence and sorrow, she said, finally pushed her over the edge.

Read More: ‘Our Death Is Pending.’ Stories of Loss and Grief From Gaza

It would be easy to lose faith when inhumanity surrounds us. It may sound strange but, after surviving five months of brutal war, the start of the holy month has in some ways deepened my faith.

I wish this year that fasting was only about purifying our souls from the body’s mundane desires. But, for us Gazans, it has also meant learning to live without many people we love. I hope that they are in a better place now.

For those of us who live on, we also think of the homes and communities we have built with love and care that no longer exist. Even if, after Ramadan, the war ends, as we are all fervently praying for, everyone in Gaza knows nothing will ever be as it was again.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com