Presidential photographers are afforded access to their subjects that most journalists only dream of. Pete Souza, David Hume Kennerly, Eric Draper — all are well-known names in the photographic community for their day in, day out documentation of the White House. Part journalist, part historian and part public-relations agent, the president’s official photographer chronicles both the official and the private workings of some of the most public men in the world.

The beauty of the job is that the photographer — spending nearly every waking second with the Commander-in-Chief, photographing cabinet meetings, foreign trips and ‘off the record’ family events — needn’t decide whether a given moment is important: instead, the official photographer records everything, letting history ascribe significance to the people and instances locked away in the images of the presidential archive.

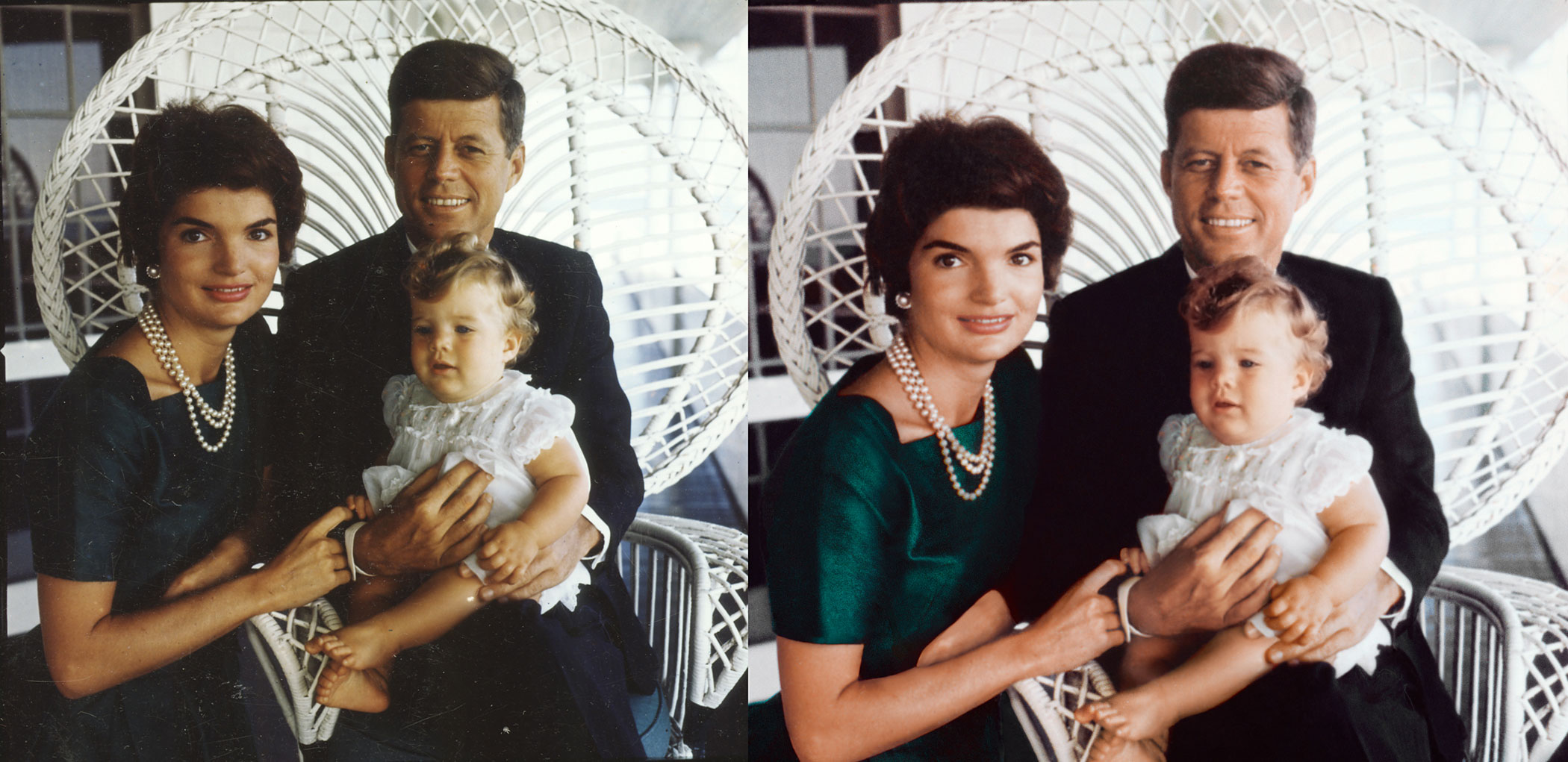

But what happens when that archive is destroyed? That’s precisely what happened to some 40,000 negatives of the Kennedy family made by Jacques Lowe. Hired two years before JFK entered office, Lowe was charged with documenting the Kennedy family. Just 28 years old when he started in 1958, Lowe chronicled Kennedy’s Senate re-election campaign, his first years as president and the family’s frequent breaks from the spotlight in Hyannis Port, Mass. and McLean, Va. His images strongly shaped and influenced the public perception of the era that would come to be known as Camelot.

“There are no words to describe how attached my father was to his Kennedy negatives,” writes Thomasina Lowe, Jacques’ daughter, in the introduction to Remembering Jack, a book published in 2003 on the 40th anniversary of JFK’s assassination. “They defined who he was as a person and as a photographer. Those images were priceless, their value beyond calculation. So he stored them in a fireproof bank vault in the World Trade Center.”

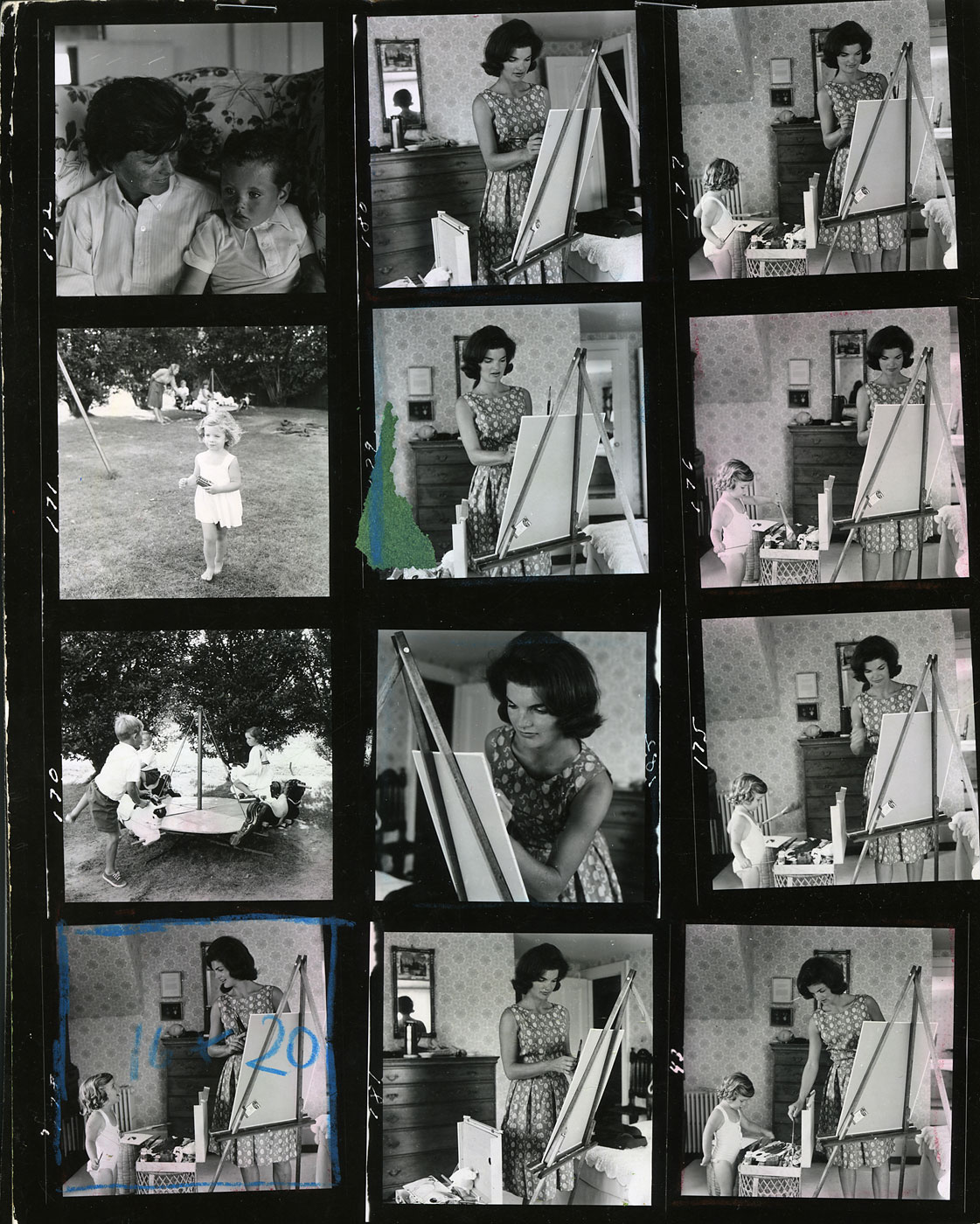

Lowe’s original negatives were destroyed on September 11th, 2001, during the terror attacks on the World Trade Center. But miraculously, some 1,500 of Lowe’s contact sheets and prints from the Kennedy file escaped destruction, stored safely at another facility in New York City.

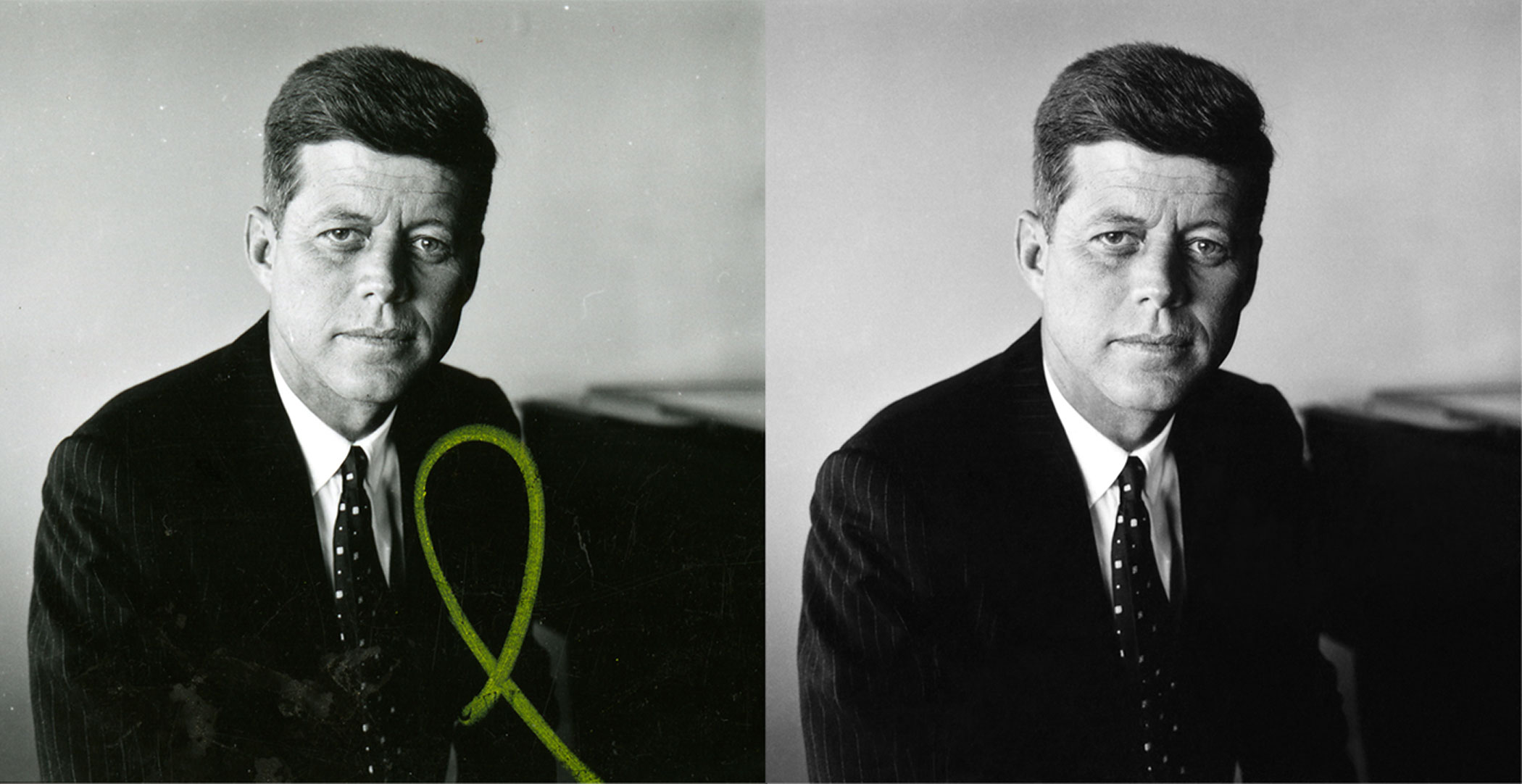

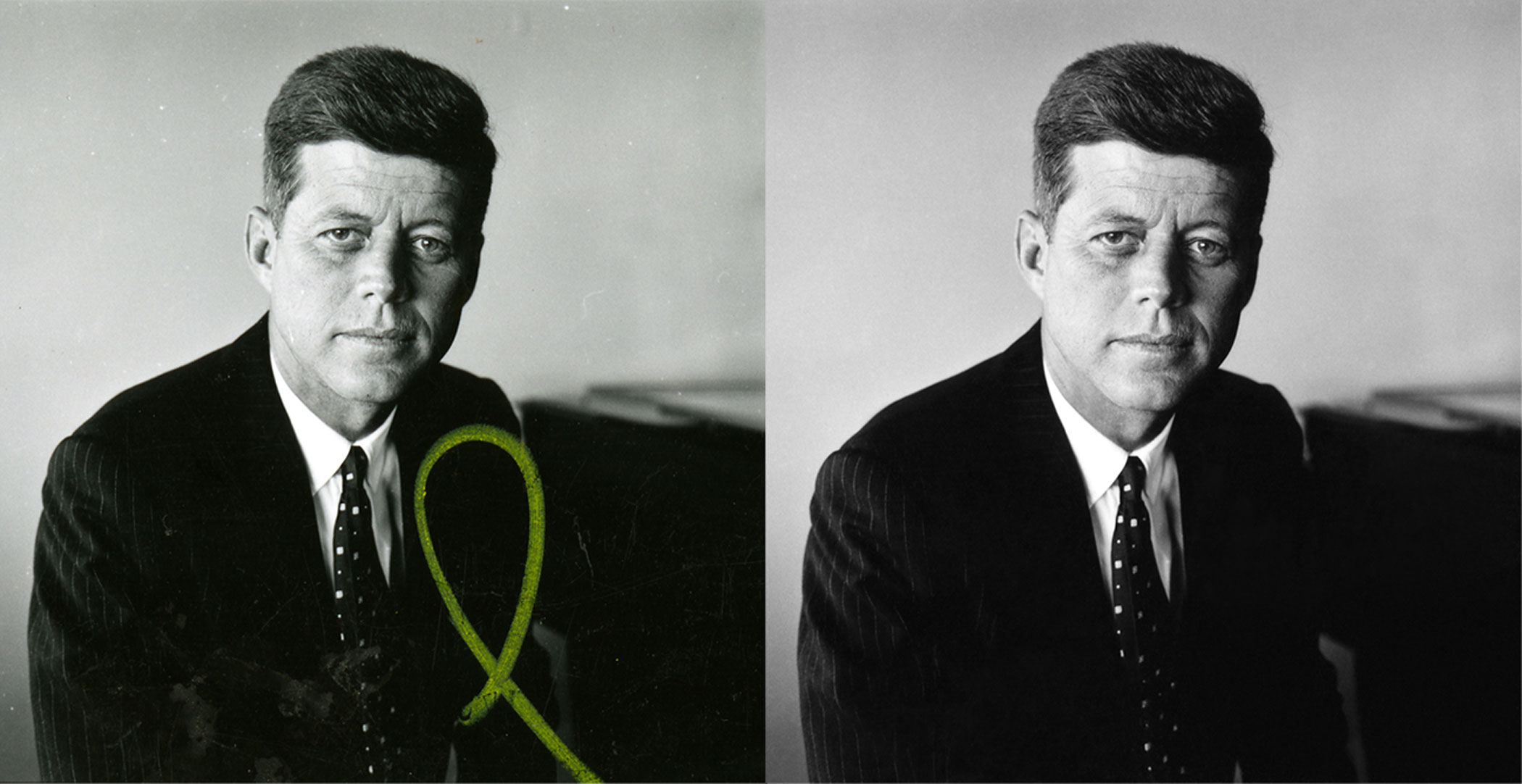

A new exhibition at the Newseum in Washington D.C. highlights 170 of the salvaged images. Restoring them to recognition, however, was far from easy: a team of seven imaging specialists spent more than 600 hours diligently bringing to life iconic images from fading contact sheets, unpolished work prints and creased proofs.

Indira Williams Babic, the senior manager of visual resources at the museum, explained her team’s exhaustive process to TIME.

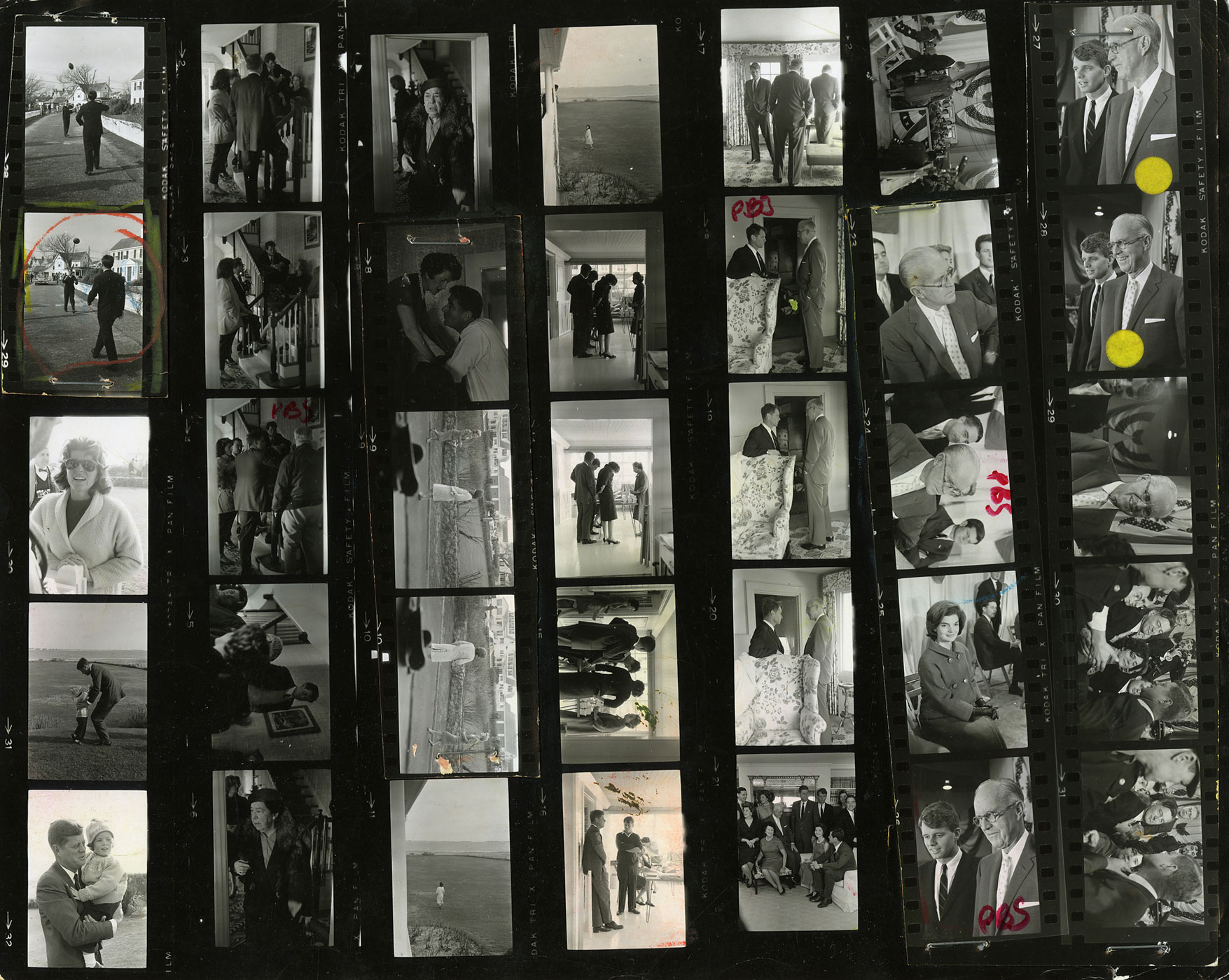

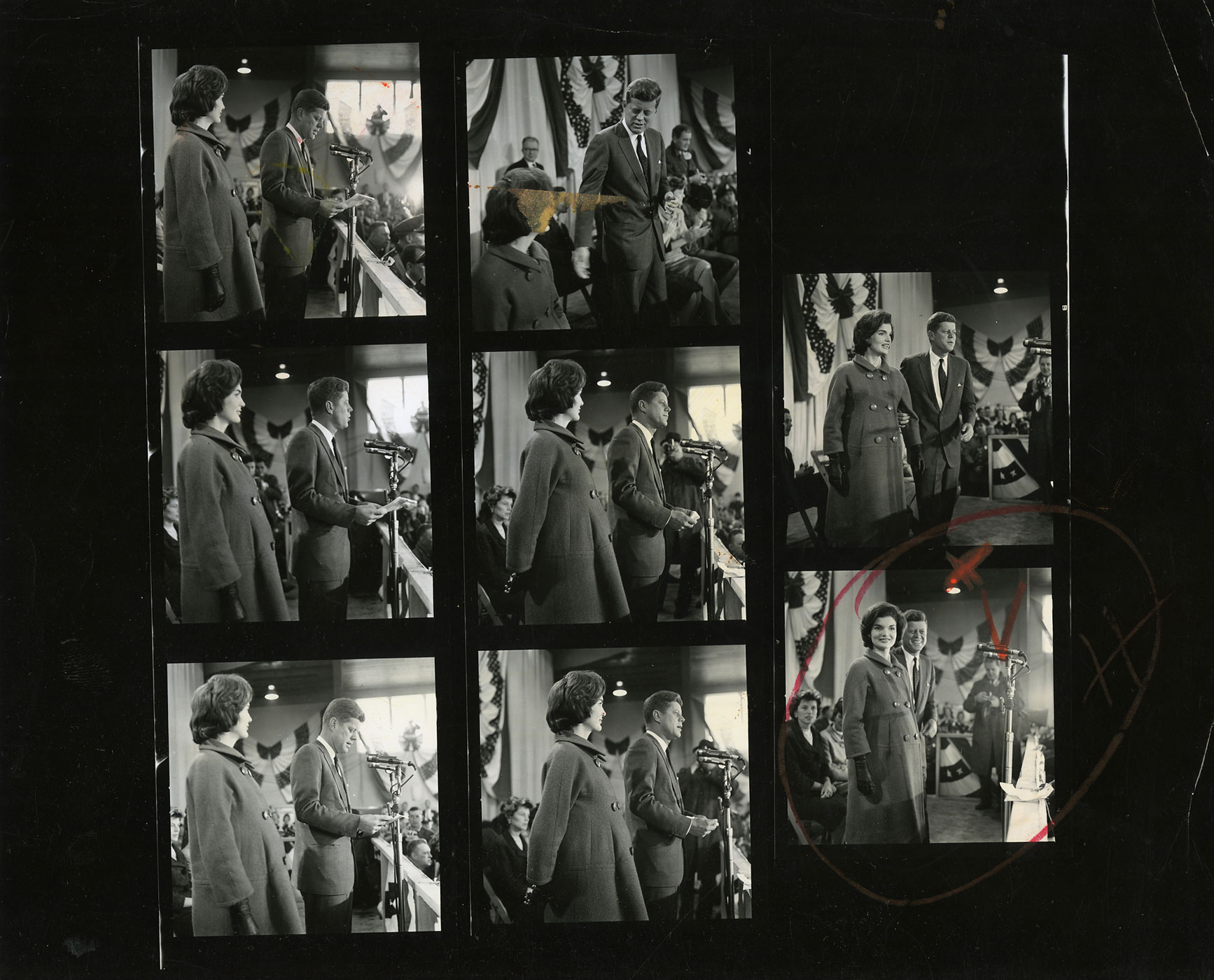

“There wasn’t anything first-generation that we could work off of,” she said. “We pored through around 40,000 images, give or take.” Pairing down the initial selection to around 1,000 images, Babic then sorted the photographs into smaller groups by content or location.

After this initial inventory, the Newseum’s design team began to figure out what the show would look like. These decisions dictated the specific restoration challenges ahead, e.g, if the design team wanted 60-inch prints from a 1-inch contact proof covered in pen markings and scratches.

“You know it’s going to be incredibly challenging,” Babic explains, “not to make it look artsy and beautiful, but the way it was supposed to look. We’re a news museum, so at the top of the list, we have to respect the photojournalist and his vision. We’ll make it big, make it beautiful, but make it real — that was the tough part.”

Many of the contact sheets were marked with scratches and printing notes. Babic points to the paradox of finding one of Lowe’s particularly-recognizable images amongst the thousands: the best photographs frequently had the worst damage. More often than not, the iconic frames on the contact sheets were covered with the photographer’s writing or surrounded by an excited scribbled circle. Every inch of stray pen mark could add numerous days to the restorationist’s workload.

Babic described the process as a dance — restoring the recognizable frames that the public expects from Lowe while also remaining realistic about what could be salvaged from the limited sizes of the original proofs.

And even after the team “restored” an image, the team often wasn’t satisfied. In some cases, they started the process over — even after hours of work — when the quality of restoration didn’t feel quite right. “You can click on white specks only so many times…but we didn’t give up,” Babic jokes.

Restoring from contact sheets also had this unique advantage: the images immediately surrounding the iconic frame often provided important historical details that the team could use as references. Rather than guessing about a detail that might have been obscured on a well-known image, the team was able to verify objects hidden beneath a scratch or a pen mark by comparing the picture to other, nearby frames.

Thus, more than a decade after the single most horrific and memorable day in modern American history, and just over 50 years after the short, legendary JFK presidency, important pictures that might have been lost to history have, in a sense, been pulled from the ashes.

Creating Camelot: The Kennedy Photography of Jacques Lowe is on view at the Newseum in Washington D.C. from April 12 through January 5, 2014.

Vaughn Wallace is the producer of LightBox. Follow him on Twitter @vaughnwallace.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com