Updated June 27, 2013

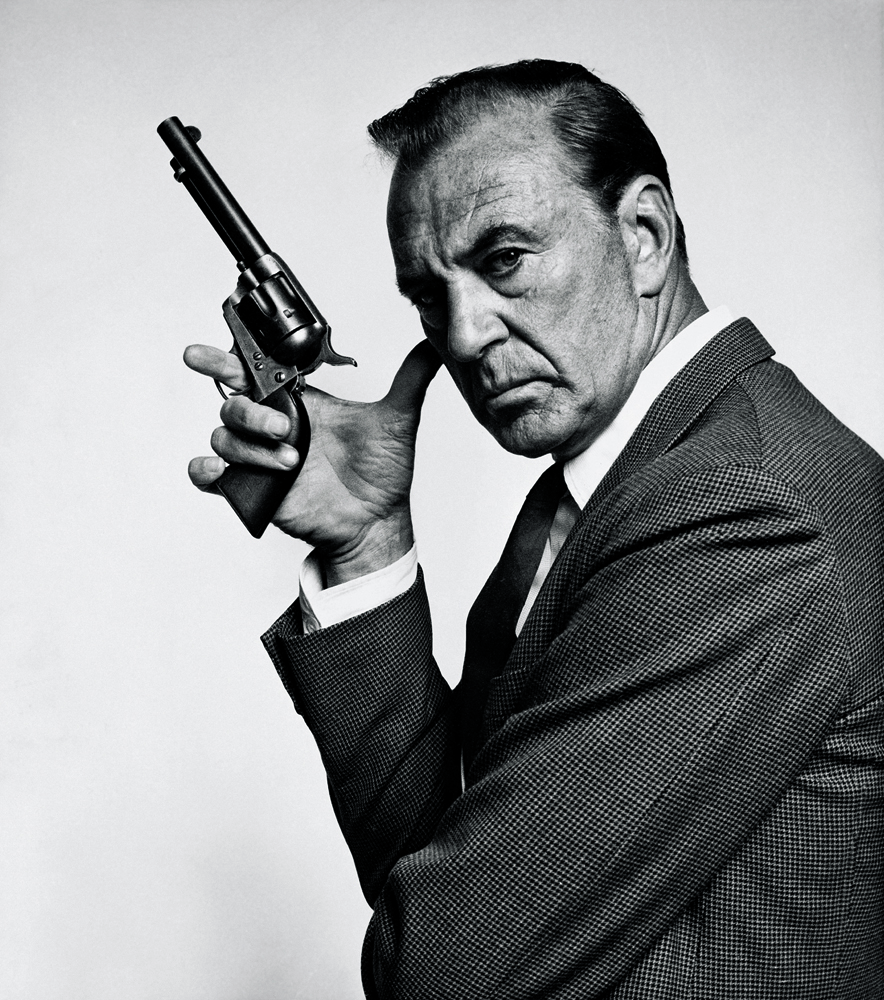

Bert Stern, known for his groundbreaking photographs from advertising’s Golden Age and his iconic portraits of Marilyn Monroe, died Tuesday at the age of 83 at his home in New York. In tribute and memoriam, LightBox presents our feature with Stern from earlier this spring, including an interview with the original ‘Mad Man’ about his inspirations and passions.

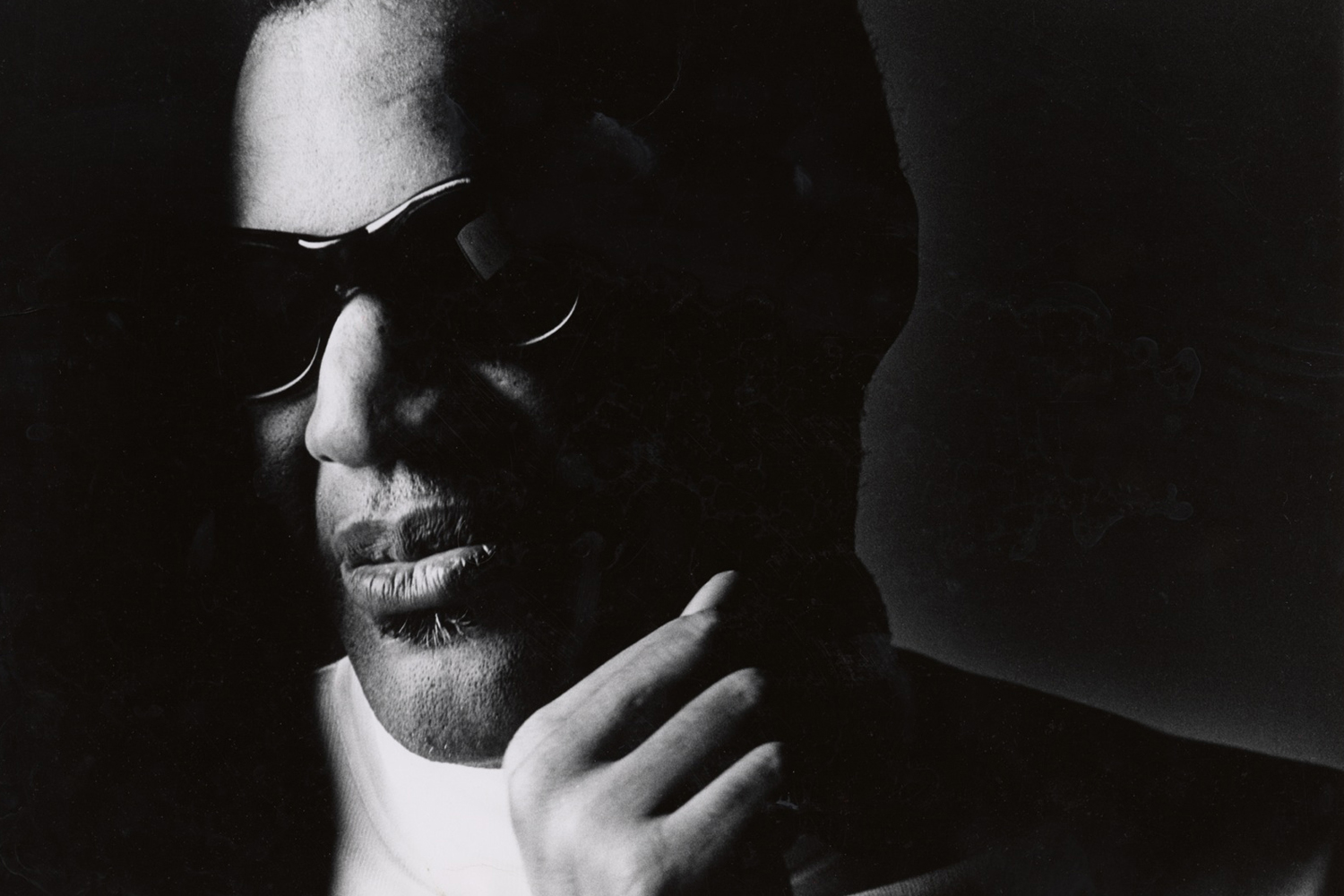

In the early 1960s, Bert Stern was one of the most successful, creative and highly paid photographers of the day. His meteoric rise had seen him produce some of the most original and remarkable images at the inception of advertising’s Golden Age, a seminal documentary film, Jazz on a Summer’s Day, and iconic portraits of some of the world’s most famous stars — including the celebrated “Last Sitting” photographs of Marilyn Monroe.

Lauded professionally, and in his private life married to a beautiful dancer, Allegra Kent, with whom he had three children, Bert Stern seemingly had it all.

As the decade drew to a close, he opened and outfitted the first photo super studio where he made photographs for prestigious editorial clients and advertising campaigns — conveyer belt style — working on as many as seven shoots a day. He also began to experiment with his own self-funded “art” projects.

But by the early Seventies Stern’s exhausting, Blow-Up-like lifestyle — fueled by amphetamines and shadowed by overhead costs—had drained him. He was hospitalized; his marriage crumbled. Broke, he left New York for Spain. He had lost virtually everything.

On the theatrical release of a remarkably candid and revealing feature-length documentary on his life, Bert Stern: Original Mad Man, TIME sat down with Stern at his New York apartment to talk about his passions (women and photography), advertising, inspiration and Marilyn.

Stern grew up in Brooklyn. At the age of 16 he started work in the mail room at Look magazine. “I loved that job,” he says — but he was destined for bigger things.

At LOOK he met Stanley Kubrick, the magazine’s youngest staff photographer. Stern and Kubrick shared “a mutual interest in beautiful women” and formed a close and lasting friendship. He also connected with art director Hershal Bramson and, although he had no formal design training, became his assistant.

Stern left to take a position as Art Director at Mayfair magazine, before reuniting with Bramson at the newly founded Flair magazine.

While at Mayfair Stern bought a camera, learned how to develop film and make contact sheets.

“Since I was the art director of the magazine I figured I might as well shoot some of the pictures — [so] I became the Art Director and photographer.”

Stern’s trajectory was interrupted by the Korean War. In 1951 he was drafted into the U.S. Army. But Stern never made it to Korea: instead, at the recommendation of an old friend who was already stationed in Tokyo, Stern was diverted to Japan and assigned to the photo department. He learned to use a film camera and made motion pictures of news events for the army while taking stills for himself.

(LIFE.com: Bert Stern’s Celebrity Portraits of the 1960’s)

After being discharged from the service at war’s end, Stern was undecided whether to pursue art direction or still photography. Flair had closed and Bramson now worked for a small advertising agency, Lawrence C. Gumbinner. He invited Stern to experiment with him on a campaign for Smirnoff vodka. The company wanted to switch from drawings to photography. Stern shot test stills for layouts — which were approved — and when Irving Penn turned down the job Stern was awarded the campaign.

“I bought new a car from the GI Bill of Rights and drove to the white sands desert of New Mexico to photograph Hershal’s ‘Driest of the Dry’ concept.”

Stern’s first Smirnoff picture won an award. His photo career was launched.

“I liked advertising. There was an opportunity to try different ideas. And we tried to shoot pictures that had never been seen before in ads.”

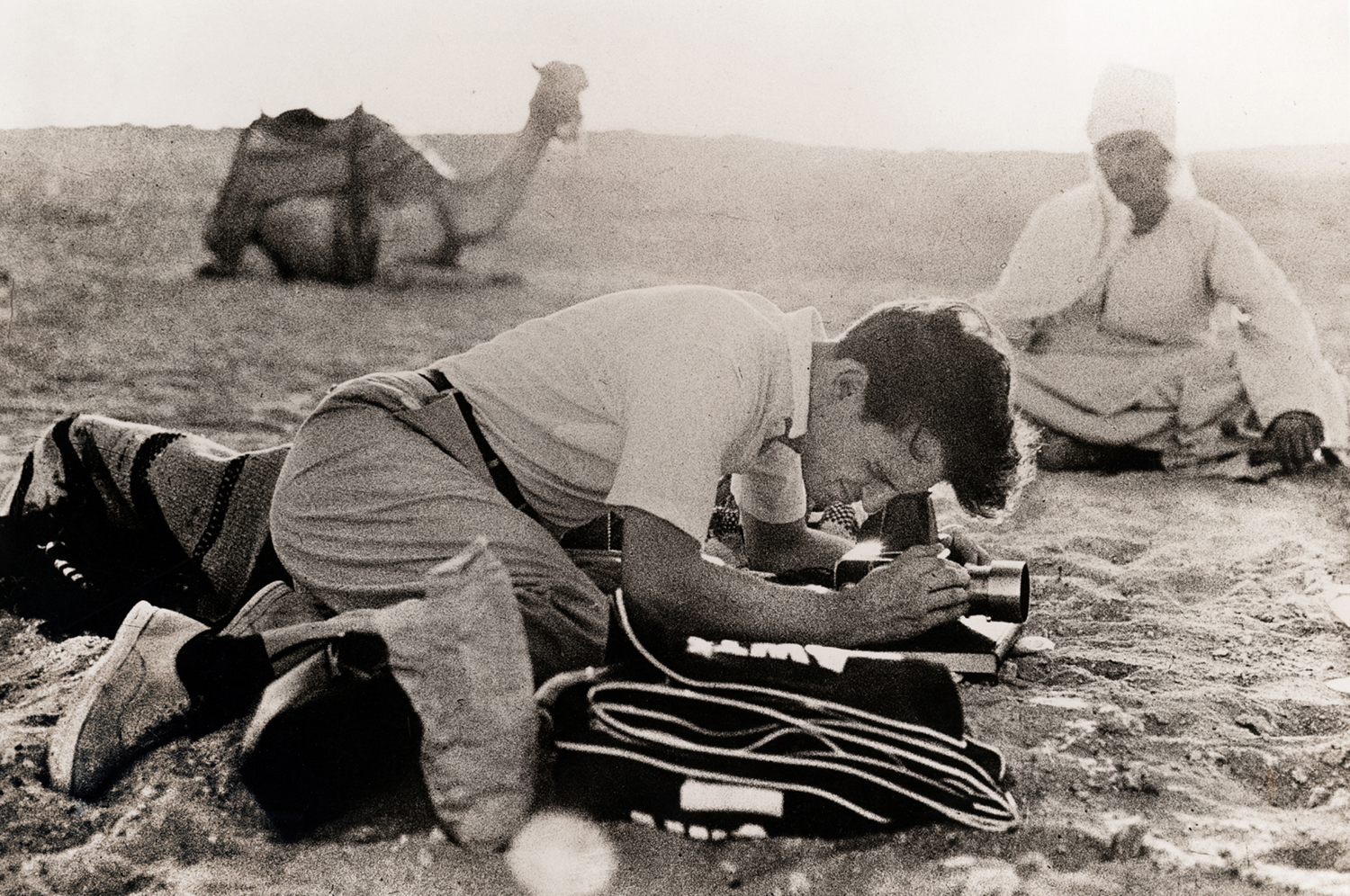

Walking on 5th avenue with a Martini glass filled with water, for inspiration, Stern noticed the Plaza hotel was inverted in the glass that acted like a lens and turned the image upside down. “I came up with the idea to photograph the Pyramid of Giza upside down in the glass — but I would have to go to Egypt to do it.”

The pyramid photograph is emblematic of Stern’s groundbreaking work and the creative explosion that marked advertising in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

In 1962, when he had begun shooting personalities as well as ads, a call from Twentieth Century Fox to photograph Elizabeth Taylor on the set of Cleopatra took Stern to Rome. Stern was afforded the freedom to do whatever he wanted to do. “I didn’t shoot set pictures,” he told TIME. “I tended to want to shoot portraits. Richard Burton — who I had already shot in my studio in New York — was playing Marc Anthony and they [Taylor and Burton] began an affair. I became friends with the two of them and began to hang out with them off set — I would shoot more candid, fun pictures.”

For Stern, taking photographs was like making love — an intense, emotional experience. “I fell in love with everybody I photographed,” he says today.

Around the same time as the Cleopatra shoot Stern received a call from Glamour with an offer to shoot for them. “I really had my heart set on working for Vogue,” he says, but made a deal with the art director. “If I shot for Glamour I could shoot for Vogue.”

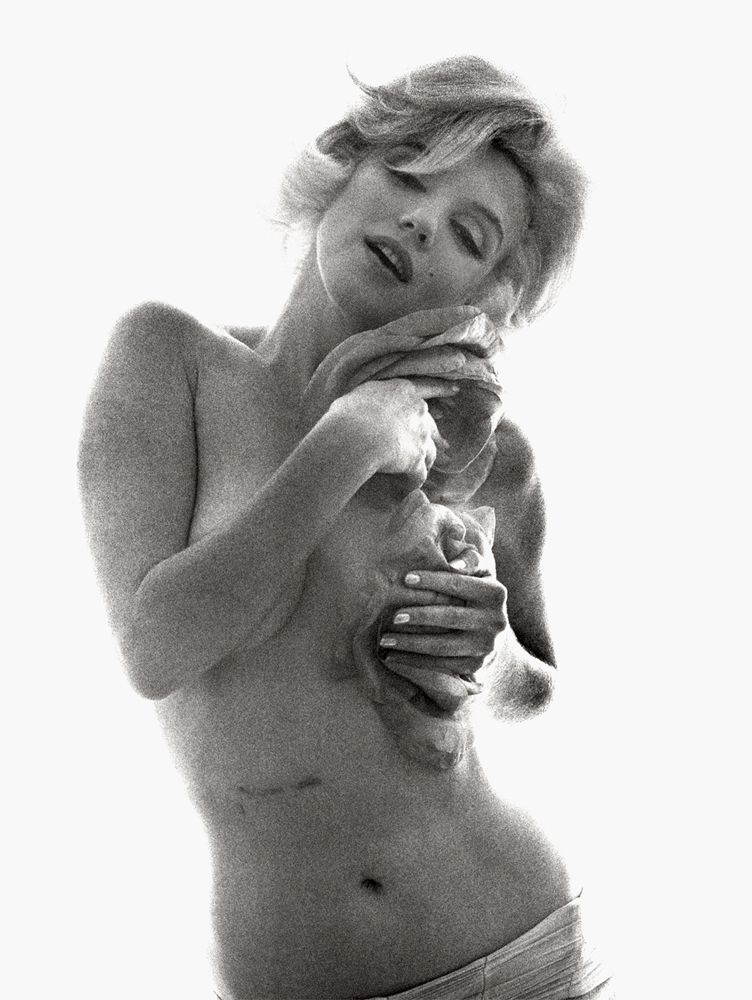

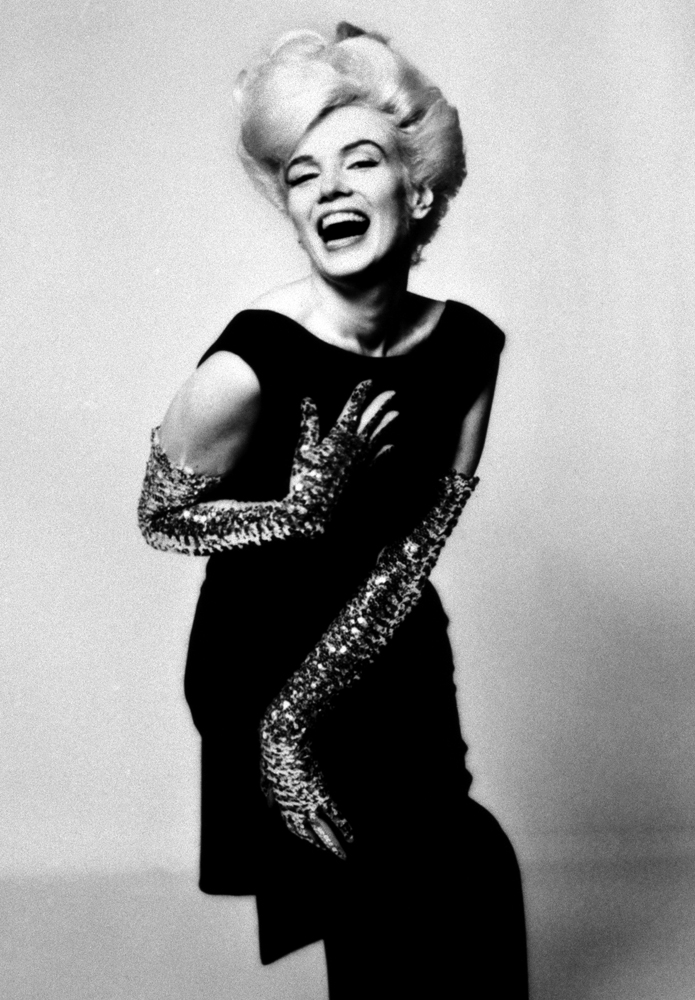

“At Vogue I had signed a contract [that stipulated] I had a certain amount of pages where I could do whatever I wanted. I realized Marilyn Monroe had never been photographed for Vogue. I didn’t want to shoot fashion so they sent me to the accessories department and gave me a little suitcase with scarves and jewelry. I thought we’d adapt one of the large suites at the Bel-Air Hotel.”

As Stern writes in The Last Sitting: “There were two Bert Sterns. One was the Bert Stern who had been accused of playing it close to the edge… Who had married his first wife with his fingers crossed…who thought his second, real marriage was over six months after it began…who had an appointment with blond destiny. That Bert Stern would gamble everything he had for a night with Marilyn Monroe. The other was Bert Stern, husband father, provider photographer who was going to get the picture, get out of there, go home to his wife and baby, and live happily ever after.”

“After I set up the studio [at the Bel-Air] the front desk rang ‘Miss Monroe is here’ I decided to go down and meet her. I met her [for the first time] on the pathway to the suite. She was alone wearing a scarf and green slacks and a sweater. She had no make up on. I said ‘You’re beautiful,’ and she said, ‘What a nice thing to say.’”

“[In the suite] she looked at what was there and asked about makeup. I said I didn’t think we needed any makeup, but how about a little eyeliner? She picked up one of the scarves, which was chiffon, you could see through it. She looked [at it] and said, ‘Do you want to do nudes?’ So it was her idea.” The photographs were taken during a 12-hour session, which ran through the night until dawn. “She was very easy to work with.”

“I brought the film back to New York and showed them to the the art director, Alexander Lieberman, at Vogue, who thought they were wonderful.” Shortly after Stern received a phone call telling him they loved the pictures so much they wanted him to go back and shoot some fashion.

Stern returned to LA and photographed Marilyn for two more days. This time it was much bigger production with a fashion editor and Stern found it difficult to make the same spontaneous pictures. But once Marilyn tired of dressing up Stern got everyone else out of the room, leaving he and Marilyn alone — to make more photos with his original intent. The images from that assignment remain some of the most iconic and intimate celebrity portraits ever made.

Stern submitted his pictures — this time shot in black and white, as opposed to the earlier color pictures — and Vogue made the layout with the second sitting only, none of the color nudes were used. “They called me up to see the layouts,” Stern recalls. “There was something haunting about them. That Monday, she died.”

Vogue had sent Marilyn the photos from the first day for approval—it was not usual practice but for Marilyn they had made an exception. “A lot of the pictures she had put markings on with magic marker, directly onto the transparency [to indicate images that didn’t reflect her own self-image]. I thought it was interesting but I didn’t think I would use them. Then the art director Herb Lubalin heard about [the crossed out frames] and said they would like to use them in a new magazine they were starting, called Eros. They talked to her PR people and they had no objections.”

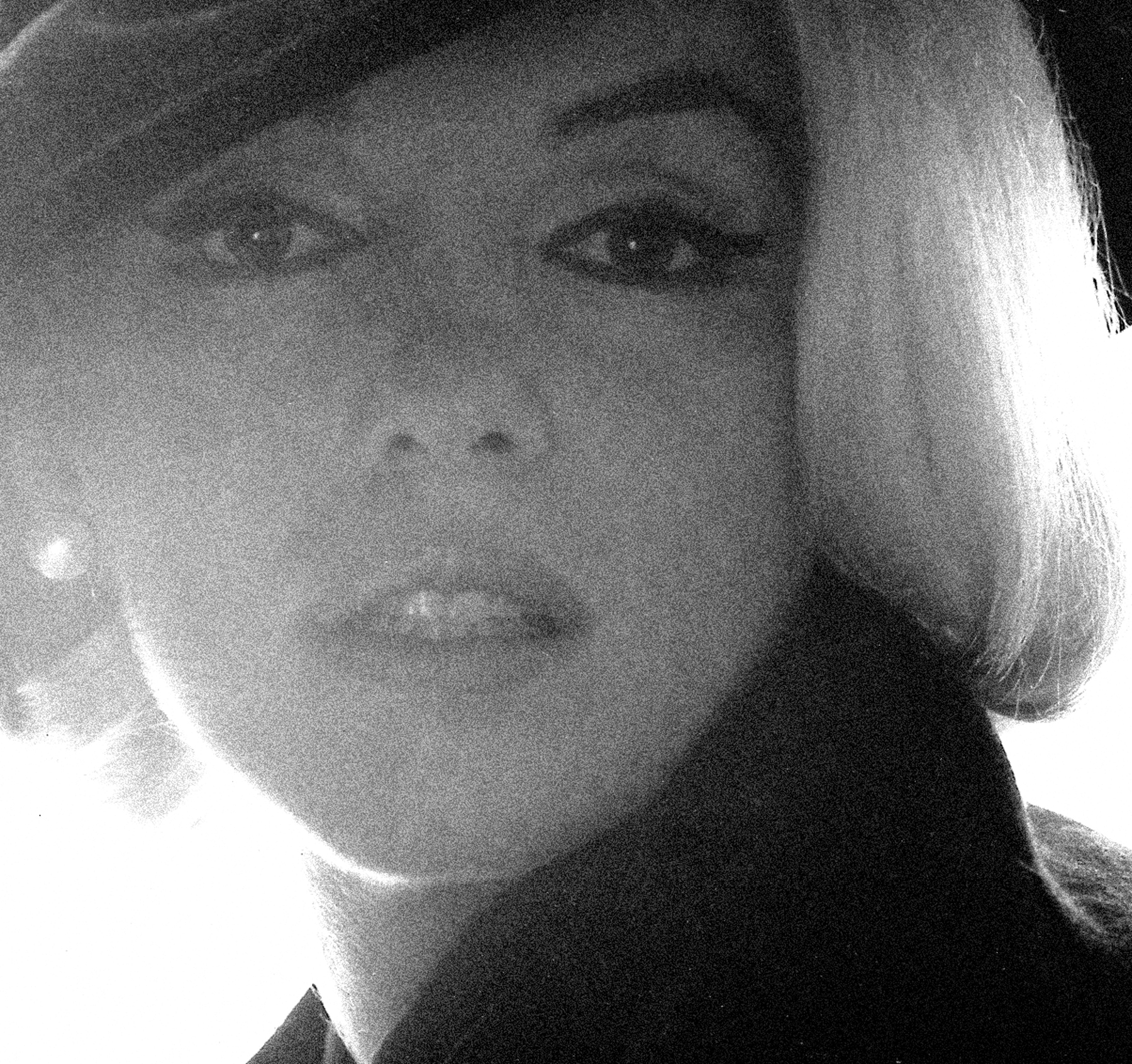

The same year, 1962, also saw the release of Lolita, directed by his old friend Stanley Kubrick. He asked Stern to take some publicity shots for the film. Stern took then 13-year-old actress Sue Lyon and her mother to a five-and- dime store in Sag Harbor, on eastern Long Island, to make the pictures. “I walked into the store and saw all these sun heart-shaped sunglasses and candy canes and other fun stuff that became the props for the shoot. I had not seen the movie but I underlined passages in Nabakov’s book that would make picture ideas. I always work with words that become pictures.”

Stern, it seemed, could do no wrong. “I was having a great time. Life was all work, work was all life.” But by the late Sixties, things began to unravel.

As Stern writes in The Last Sitting: “The Sixties were the best and craziest decade, not only of America’s life but of mine. Those were the years of the jukebox, and the big sound, and the big bucks, and the swimming pool, and the three children, and the townhouse, and the houseboy, and the black library with the Picasso over the door, Dr Feelgood, and the crystal blue Stingray, airplane trips to Fire Island, and the fantasy house with the wishing well, the herb garden, and the eight-foot tall roses Allegra grew while I photographed American beauties in New York”.

His marriage collapsed, as did his health and his finances. “I was broke. I shipped everything I owned into a twenty-foot container and went to Spain to stay with a friend.” His marriage was irreparably damaged, but he returned to New York and set to work, trying to rebuild his life.

Inspired by the PDR (Physicians Desk Reference) he conceived The Pill Book — a photographic compilation of different pills which he shot as simple still lifes. The book, of which there are now more than 18 million copies in print, put Stern back on track, and by the late 1970s he was photographing portraits and fashion again.

In 1982, the twentieth anniversary of Monroe’s death, Stern published the The Last Sitting, a comprehensive edit of his Marilyn pictures, the overwhelming majority of which had not been seen. Vogue ran a 12-page story and this time included some of the images that Marilyn herself had crossed off.

A year later a friend introduced Stern to Shannah Laumeister, a 13-year-old girl he photographed, after which he simply filed away the photos. Four years later, they reconnected for a second shoot. Over the past three decades the two have built a close bond. “Our whole relationship has been sourced through a camera … and has grown closer and closer [until we know] each other’s souls,” Laumeister told TIME.

Six years ago, Laumeister turned the tables — and her camera — on Stern and began to make a documentary of his life.

The resulting film, Bert Stern: Original Mad Man, is a candid and revealing portrait of the photographer — in Laumeister’s words, it’s “an imperfect movie … dealing with the controversial nature of who people are. We are all contradictory, and if you turn a camera on anyone’s life they’ll have plenty of reason to hide.”

Laumeister and Stern’s relationship — one of muse and mentor — is intimate and complex, and this unconventional film reflects that. “I wanted to try to keep it that way [intimate, just the two of us], because I felt that would make it special. It mirrored how he got such great pictures — he got everyone out of the room so he could get that personal connection” with his subjects, Laumeister says.

A 50-picture exhibit at Staley-Wise, curated by Laumeister, will coincide with the film’s release.

“He took the quintessential pictures of Marilyn Monroe,” Laumeister says, “and that work can sometimes trump [everything else he’s done]. There are so many more photos, even of Marilyn, and the show is representative of his wider work and ideas.”

As a new season of Mad Men premieres, it’s perfectly fitting that the original mad man, Bert Stern, is receiving the accolades that his remarkable life and career deserve.

Bert Stern was a New York-based photographer famous for his ‘Last Sitting’ photographs of Marilyn Monroe and his groundbreaking advertising photography.

‘Bert Stern: Original Mad Man’ opened in New York on April 5, 2013. A gallery show coinciding with the film opened on April 4 at the Staley-Wise Gallery, New York.

Phil Bicker is a senior photo editor at TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com