For many Russians, March 1 was a day of mourning. The memorial service for Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who perished weeks earlier in a remote Arctic penal colony, was being held in a small church on the outskirts of Moscow. Despite the heavy police presence and in defiance of the Russian government’s warnings against unauthorized gatherings, tens of thousands of people turned out for the funeral, with many chanting “Putin is a killer!” and “No to war!” It was the largest protest Russia had seen since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine two years ago—a fitting tribute for a man best known for his ability to draw Russians onto the streets to demonstrate against Russian President Vladimir Putin’s rule. Several of those people have since faced arrest.

Thousands of miles away, in a bright conference room overlooking London’s Finsbury Square, Evgenia Kara-Murza is appalled. “It’s so grotesque, so Kafkaesque,” she tells TIME of the Kremlin’s handling of Navalny’s funeral and the crackdown on those who have tried to pay their respects. In an alternate universe, perhaps she would have been among them. The service, after all, was being held just a stone’s throw from her parents’ home in Moscow. Like the scores of people lining up around the church that day, she saw Navalny as a key leader in the fight for a free and democratic Russia—or, as he called it, “the beautiful Russia of the future.” But sitting here in London, Evgenia doesn’t have time to mourn. Later this afternoon, she will meet British Foreign Secretary David Cameron about another enemy of the Kremlin: Her husband, the prominent Russian opposition politician and journalist Vladimir Kara-Murza, who has been languishing in a Siberian penal colony since 2022.

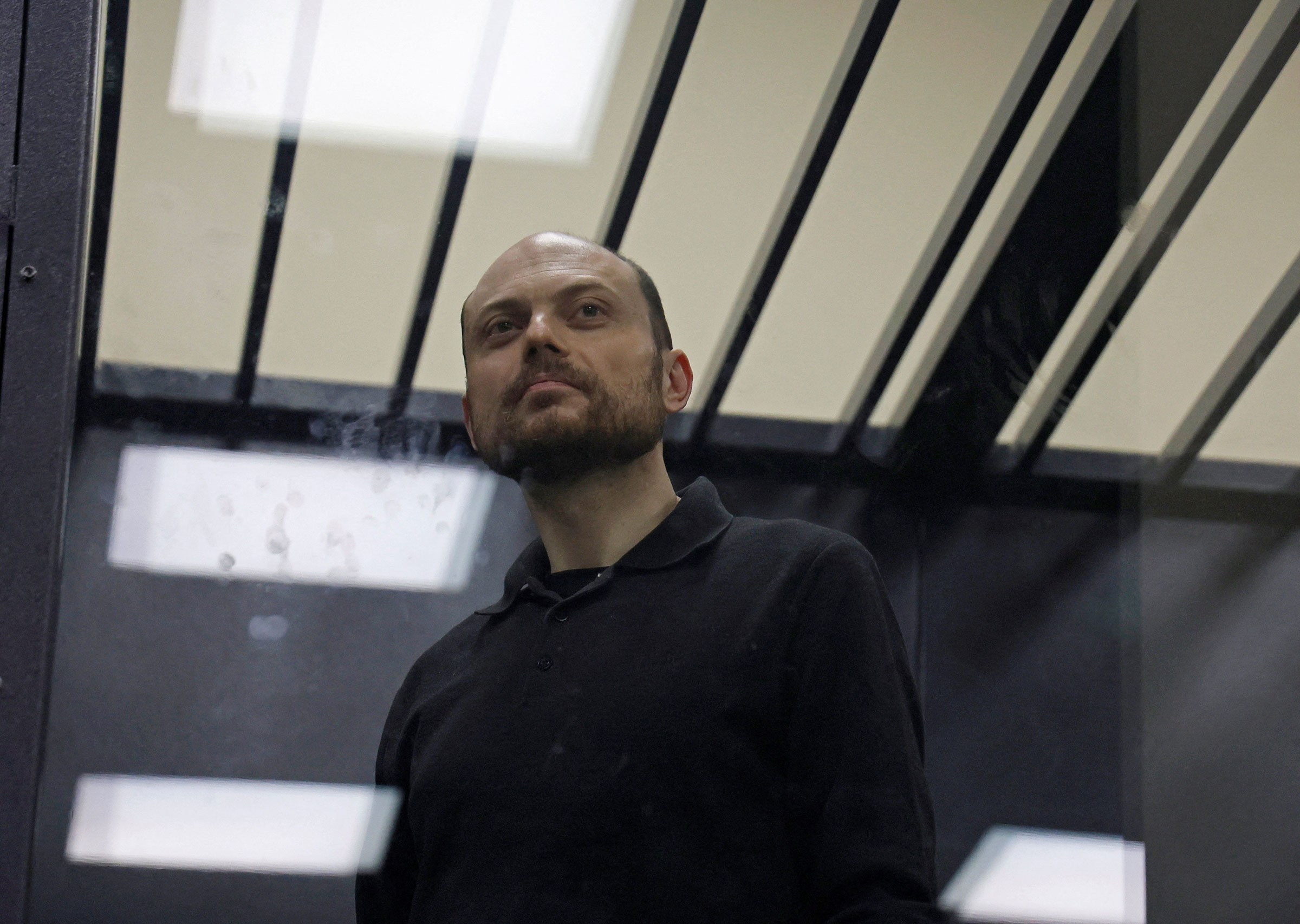

With Navalny dead, Vladimir is now Russia’s most high-profile political prisoner—and perhaps its most vulnerable too. Back-to-back assassination attempts have deteriorated his health, and many now fear that if Navalny could be killed (the Kremlin claims the 47-year-old died of natural causes; his family and most other observers say the responsibility for his death lies squarely with Putin), Vladimir could be next.

Though Evgenia’s meeting with Cameron was scheduled weeks in advance, Navalny’s death has injected greater urgency into her appeals for the U.K. and other countries to take quicker and more proactive steps to free political prisoners like her husband—efforts that, at least in Britain, have been derided by both the families of those detained and British lawmaker alike as woefully inadequate. Just days after news of Navalny’s death broke, a U.K. Foreign Office minister ruled out the possibility of a prisoner swap to secure the release of Vladimir, a dual Russian-British national. But if there’s any lessons to be taken from Navalny’s death, it’s that “just saying that we do not engage is not acceptable anymore,” Evgenia says. “We see that whether governments engage or not, the number of hostages and political prisoners is on the rise.”

More specifically, Evgenia wants the U.K. government to establish a dedicated office to deal with its arbitrarily detained citizens abroad akin to the U.S.’s Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs. She also wants Western countries to automatically deploy punitive measures laid out in the Global Magnitsky Act, a sanctions regime adopted by the U.S. and other countries to target human rights violators and corrupt actors. Vladimir was one of the key campaigners behind the legislation, which was adopted by the U.S. in 2012. Still, Evgenia says she had to campaign for months for the U.S. to sanction those involved in his detention. “Such instruments should be used automatically,” she says, snapping her fingers, “without anyone having to campaign for it for months and years.”

Read More: The Fight to Free Evan Gershkovich

As Russia prepares to hold its presidential election this week, Putin is all but guaranteed to secure an absolute victory. With the electoral system heavily skewed in his favor and all significant opponents disqualified, jailed, or dead, the vote itself is almost entirely pro forma. Still, the Russian opposition lives on—not just in would-be leaders behind bars such as Vladimir, but in the spouses like Evgenia who take up their advocacy when they’re no longer able to do it themselves.

“She basically stepped into his shoes and took over from his work as a member of the Russian opposition, speaking not just about his situation, but about the situation of other political prisoners,” Bill Browder, a British American anti-corruption campaigner and close friend of the Kara-Murza family, tells TIME. “She feels it’s her duty to be the best possible representative of him when he’s unable to represent himself.”

When TIME first sat down with Evgenia last year, on the sidelines of the 15th Annual Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy, she stressed that unlike many of the other attendees, she was no politician. “I never wanted to be a public figure,” she said at the time. “I never wanted to be a public speaker.” Yet there she was, delivering speeches and giving interviews about the plight of political prisoners, the need for Magnitsky sanctions, and the importance of supporting Ukraine against Russia’s ongoing invasion. Since taking up the mantle of her husband’s activism following his arrest in Moscow in April 2022 for criticizing the war in Ukraine, she spends most of her days traveling the world to meet with foreign dignitaries, testify before committees, accept awards, and talk to journalists—all in a bid to bring her husband, and the scores of other political prisoners in Russia, home.

Though being away from her family isn’t easy, Evgenia is used to a nomadic lifestyle. While she was born on the Kuril Islands in Russia’s far east, her father’s coast guard career took her family all over the Soviet Union during her childhood, from Sevastopol to St. Petersburg to Tallinn in modern-day Estonia. The frequent travel “made me a bit of a cosmopolitan,” she says. “I can build my nest anywhere—I just need the people I love around me, and I build my nest around the people I love.”

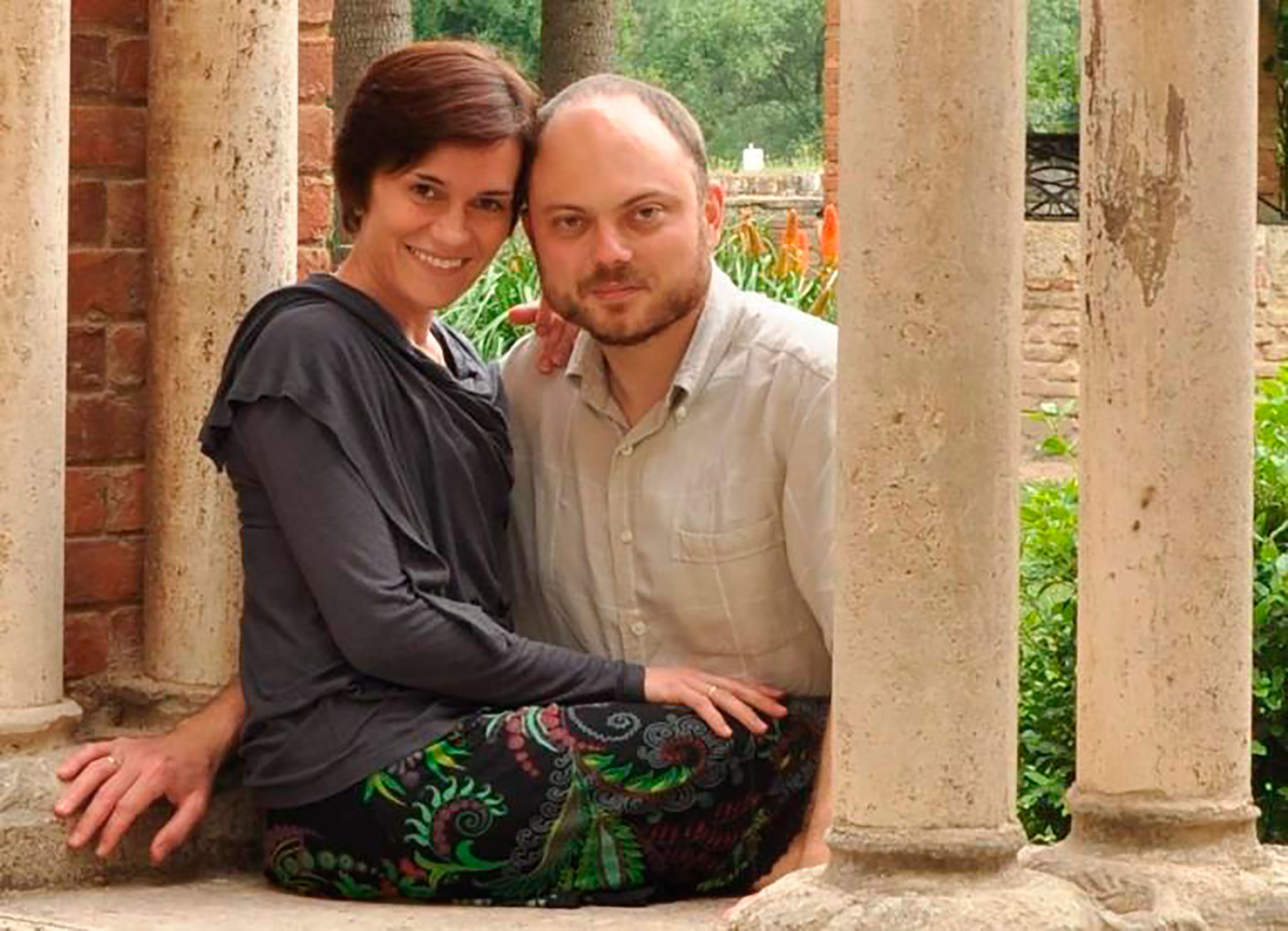

Before long, her family decided to settle in Moscow (young Evgenia needed stability, her mother argued), where at the age of 11 she would meet Vladimir Kara-Murza, one of her classmates. Though they would ultimately go down different paths—at 14, Vladimir moved with his mother to Britain, where he remained until he graduated from Cambridge University; Evgenia finished her schooling in Moscow, where she pursued a degree at Moscow State Linguistic University—they reconnected in their 20s and have been together ever since.

Evgenia says she always supported her husband’s pro-democracy work, even as the space for him to do it within Russia began to shrink. In 2003, Vladimir stood in Russia’s parliamentary elections, becoming not just the youngest candidate, but the only one to be backed by two opposition parties, the Union of Right Forces and the social-liberal Yabloko. This on its own was a feat: The Russian opposition has long been ridden with division. “He was this rare case when the Russian opposition actually came together and agreed on something,” Evgenia says. “They agreed on Vladimir.” But the 2003 elections, while ostensibly free, were far from fair. Evegenia says that while Vladimir was permitted to participate in televised debates, his mic was turned off whenever he spoke. And while he was permitted to put up billboards promoting his candidacy, she says that the lights illuminating them after nightfall—which, during the Russian winter, was as early as 4 p.m.—were shut off. In the end, Vladimir came in second to a candidate from the ruling United Russia party.

“He was feeling very down,” says Evgenia, who at the time was working as a translator and interpreter for a French firm seeking to help Russia implement key judicial and civil service reforms. But those reforms never materialized, and a year later Putin canceled gubernatorial elections. It was around that time that the independent Russian broadcaster RTVI offered Vladimir the job of Washington bureau chief, based in Washington, D.C. “We thought it would be for a year or two, just to look around,” Evgenia says. That year turned into a decade, during which time the political situation in Russia continued to deteriorate. “The kids were born and it became apparent that if Vladimir were to continue with his work as he saw fit, the kids needed to be in a safe place,” she says. “So I mostly stayed with the kids working from home and Vladimir traveled the world, trying to bring change, to open the world’s eyes to the nature of Vladimir Putin’s regime.”

But it wouldn’t be long before Vladimir faced the consequences of his activism. In May 2015, years after the assassination of Sergei Magnitsky (the namesake of the Magnitsky Act who uncovered $230 million in Russian state corruption) and two months after the assassination of Boris Nemtsov (the liberal Russian politician and mentor of Vladimir), he was poisoned for the first time. The second would come two years later. In both cases, he fell into a coma resulting from what doctors described as “severe intoxication with an unknown substance.” Both times, Evgenia nursed him back to health, helping him relearn how to walk, to talk, and even how to eat.

“I believe this is what marriage is about,” Evgenia told TIME in Geneva. “Whenever Vladimir was in a difficult situation, I was there for him. And whenever I fell apart, he was always there for me, to pick up the pieces and put them together. … You share everything and you’re there for each other. That’s the only way to me.”

As much as Evgenia eschews the label of politician (as of 2022, her official title is advocacy director of the Free Russia Foundation, a nonprofit international organization supporting civil society and democratic development in Russia), her friends are the first to acknowledge that necessity has forced her to become one—and a good one, at that.

“I’ve worked on a lot of different advocacy over the last 15 years, and I’ve never seen somebody, including Vladimir, who’s as effective as her at convincing people to take action,” Browder says, noting that despite her stated desire to retire from politics once Vladimir is released, “Given what she’s done and what she’s accomplished and how she’s conducted herself, I think the people of Russia will need her as much as they need Vladimir in the future.”

Evgenia isn’t the only spouse who has come to politics in this way. In the aftermath of Navalny’s death, his wife Yulia Navalnaya has vowed to take up his fight. (Vladimir Ashurkov, the executive director of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, told journalists on Feb. 28 that “the exact details of her new public rule will emerge over time as the situation is very fresh and painful.”) Sviatlana Tsikhanousakaya, the leader of Belarus’s exiled opposition, rose to prominence in 2020 when she challenged Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko for the country’s presidency in the place of her husband, the jailed presidential candidate and pro-democracy activist Sergei Tsikhanouski. (A longtime Putin crony, Lukashenko overcame the democratic mobilization against his rule with Kremlin support.)

All three women represent an increasingly pronounced feminine face of anti-Kremlin activism—one that has emerged within a political culture where politicians’ wives are rarely seen, much less heard. The circumstances notwithstanding, Evgenia welcomes this change, noting that women stand to inject more values back into politics. But she also stresses that there are others, including ethnic minorities and members of the LGBTQ community, who are changing the face of the pro-democracy and anti-war movements in Russia. “It’s becoming so diverse, and it’s interesting that it’s happening under these impossible circumstances,” she says. “To me, this is a very important change because I believe that actual sustainable change should come from the bottom up, from the grassroots movement up, from people realizing their strength, from people realizing that they’re a force to be reckoned with, from people finding their voices.”

Strongmen leaders have a habit of underestimating women. Lukashenko notably dismissed the political threat posed by Tsikhanouskaya on the basis that women are simply too fragile for the presidency. If Putin views Evgenia with similar apathy, he hasn’t made it known. “In Russia, there is a very sexist culture and because of that I think that they underestimate women, and they certainly underestimate her,” Browder says. “The pressure she’s under is unimaginable. To hold it all together and to successfully carry on as she’s done is a feat of unbelievable heroism and stoicism.”

Indeed, if Evgenia has any fears for her own safety or that of her husband or family, she doesn’t show it. Throughout our conversation, she speaks with a steely, cool-headed resolve—the kind that Browder attributes both to the justness of her cause and to her being “just a really decent human being.” It’s perhaps because that cause is bigger than just her husband and her family that Evgenia never comes across as just a worried spouse. The last thing she wants is pity. “I hate condolences and expressions of sympathy because that’s not what I need,” she says. “I’m a strong girl. I can push forward. I need action.”

Still, there are times during our conversation where the toll of Vladimir’s imprisonment creeps to the surface. “I’m very bad with dates,” she confesses at one point. “There’s a cliché that men always forget dates, anniversaries, all of that. I’m this person in the family. Vladimir always keeps track, he always remembers everyone’s birthday, every year, every little thing. I cannot remember anything! If not for him, I’d be lost completely.”

When asked where she gets her strength, Evgenia quotes Eleanor Roosevelt: “A woman is like a tea bag,” the former First Lady said. “You never know how strong she is until she's in hot water.” Next month will mark two years since Vladimir’s arrest, and two years since Evgenia was plunged into her current role. The longer she’s in it, the stronger she seems to get. And the angrier, too.

“That rage that I feel because this murderous government has been trying to destroy my family for so many years, is currently trying to destroy the neighboring country and all chances for a normal future for our country—that rage, you know,” she says, before letting out a deep exhale. “A woman is like a tea bag.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Yasmeen Serhan at yasmeen.serhan@time.com