Since 1996, advocates for women’s rights have marked “equal pay days” every year to raise awareness about the ongoing gender pay gap that persists despite women's increasing educational opportunities and workplace attainment. This year, Tuesday, March 12, marks that disparity—or how far into 2024 it takes a woman who works full time to make the same amount of money a man working the same hours made in 2023. On average, women still only make 84 cents for every dollar men make, with the gap far more stark for women of color. (Native women’s equal pay day, by comparison, won’t be reached until November 21.) And these figures don't include the unpaid domestic and caregiving labor that women continue to disproportionately bear.

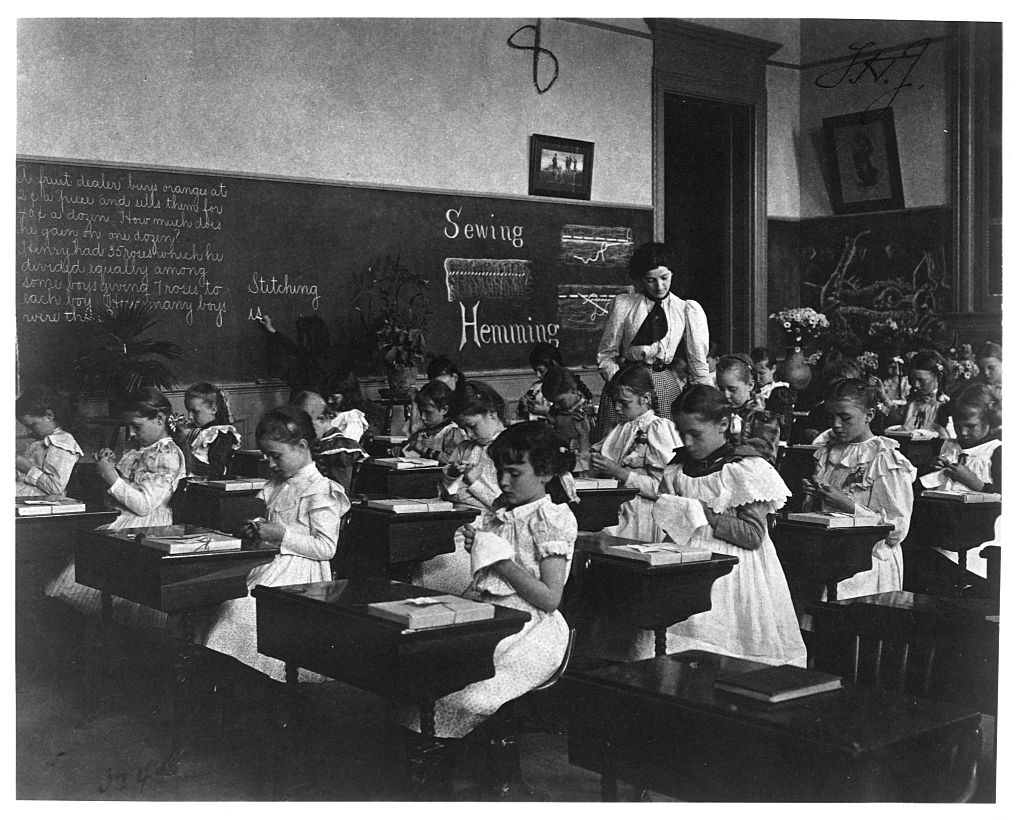

The question of how we value women’s labor is at the heart of a new exhibition we were involved in curating at the Center for Women’s History at the New-York Historical Society. The exhibition, entitled Women’s Work (on view through August 27), presents a wide-ranging look at women’s labor in New York over the past 300 years. It captures the breadth of women's experiences, while challenging the stereotypes invoked by the phrase “women’s work.”

While women have long performed labor culturally coded as “men’s work”—for example, pursuing entrepreneurial careers—the unpaid and paid work of caring for children, the sick, and the elderly, as well as performing domestic work, has long been associated with women. This is particularly true for Black women, both before and after emancipation. Even as cultural norms for elite women insisted that a woman’s place was in the home, enslaved and indentured women were coerced into unfree labor within that very home. After the legal end of slavery, Black women were pressured to maintain this dynamic by vagrancy laws and the paucity of other options in the face of continued segregation and gender and racial discrimination.

Read More: Why the U.S. Gender Wage Gap Hasn't Narrowed in Decades

On the other hand, assumptions about women’s alleged natural propensity for caregiving opened the door for some women to enter newly formed professions like teaching during the 19th century—while at the same time, positioning them to garner lower wages in those allegedly female professions than in male-dominated ones. An 1846 editorial in Godey’s Lady’s Book encapsulates, for example, why teaching has long been considered women's work. “The heart and the understanding [of children] must alike be cultivated, and this never can be effected without the co-operation of women," it declared, asserting that "school-keeping" was a natural extension of women's "influence in the nursery." Finally, the author suggested, "males might undoubtedly be engaged in business more profitable and pleasant to themselves, and their duties as teachers better as well as more cheaply performed by intelligent women.” As public school systems developed and expanded, so too did the reliance on women as teachers. By the 1880s, the majority of the nation's teachers were women; today the number remains over 75%.

Women’s entry into medicine followed a similar pattern. While women had long been engaged in caring for the sick and infirm, efforts to professionalize nursing and the founding of new credentialing institutions in the late 19th century formalized this association—often to the exclusion of women of color. Early nursing school graduates primarily served private, affluent families, with public health nursing in New York City beginning only with the founding of Lillian Wald’s Henry Street Settlement in 1893. World War I catalyzed large numbers of nurses—yet they were mostly volunteers without formal training. Indeed, some male leaders welcomed society women as nursing volunteers, reasoning that they would happily return to their homes once the war ended rather than seek paid employment.

In 1854, New York City began hiring policemen's widows to clean cells and supervise female prisoners, and in the early 20th century, some of these "matrons" were permitted to go undercover as investigators targeting abortion providers, con artists, and lesbian and bisexual women. However, they could not advance in rank or receive commensurate pay until the first decades of the 1900s.

The life of Louisa Lee Schuyler exemplifies how these gendered assumptions opened some doors for women, even as they also worked to limit women’s professional advancement and pay. Born in 1836, Schuyler began organizing philanthropic efforts as New York City's population exploded after the Civil War, and hospitals and poorhouses strained to cope with an influx of sick and impoverished patients. At a time when elite women’s public roles were limited by work that could be justified as aligning with their innate nurturing characters, she founded the State Charities Aid Association in 1872. This umbrella organization coordinated services among local groups and lobbied for social reform legislation, such as the New York State Care Act of 1890, long before women had the vote. Her example paved the way for a later generation of "new women" whose philanthropic work brought about social reform and expanded women's influence in politics and public life. Upon Schuyler's death in 1926, the New York Times wrote, "Had she been born a generation later, she might easily have become a great political leader."

While the professionalization of work viewed as extensions of women’s (supposedly innate) caregiving roles opened up paid employment opportunities for women (albeit jobs that paid less than those in male-dominated fields), not all women benefited.

In New York City’s Black neighborhood of San Juan Hill—today’s Lincoln Square—the Children’s Aid Society ran an industrial school in the early 20th century that taught vocational skills to young working-class people, including domestic labor. Domestic service was grueling and physically demanding, and women regularly encountered sexual harassment from employers. White working-class women increasingly chose to avoid it, preferring work in factories, offices, and stores. Black women faced racial discrimination that limited their employment. Philanthropic organizations facilitated this exploitative labor structure under the guise of aid, further reifying the hierarchy of women of color performing care labor for the benefit of wealthier white women. Journalists Ella Baker and Marvel Jackson Cooke exposed how these dynamics led to what they termed the “Bronx Slave Market” in the 1930s.

Read More: Women Hold the Key to a Livable World

The welfare rights movement emerged in the 1960s at the intersection of the ongoing Black freedom movement, women’s liberation, and anti-poverty activism. At the time, single mothers receiving federal welfare were not allowed to work outside their homes or engage in paid employment—yet, the aid they received was hardly enough to support a family on, which forced many recipients to consider working. Many participants in the welfare rights movement were single women of color who fought against these punitive social policies that threatened to push them into domestic and caregiving labor outside of their homes—but did not similarly value the labor they did for their own families. As activist Johnnie Tillmon put it in the inaugural issue of Ms. magazine, “If I were president, I would solve this so-called welfare crisis in a minute and go a long way toward liberating every woman. I'd just issue a proclamation that ‘women's work’ is real work. In other words, I'd start paying women a living wage for doing the work we are already doing—childraising and house-keeping.”

The repercussions of this history are still seen today. Professions like teaching that were traditionally viewed as extensions of women’s caregiving roles are still lower paid than those that were historically for men only. And according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), two out of every three caregivers in the United States today are women. This imbalance became painfully clear when COVID-19 lockdowns decimated women’s workforce participation, as they had to assume more household and childcare tasks at home, while dramatically increasing demands on professional and informal care workers.

Yet, this work—whether it is paid or unpaid, performed by mothers or other caregivers—has long underpinned the economy and been essential for continued human survival. By bringing objects and images that reflect the diversity of women’s labors, the Women’s Work exhibition shows that women’s work may be everywhere, but it is not valued equally—especially when that work involves care, and particularly when carework is performed by women of color. The exhibition ends with a provocative question that is particularly apt on this Equal Pay Day: What would it look like to truly value women’s work?

Anna Danziger Halperin is Associate Director, Center for Women’s History, New-York Historical Society, where she has curated many exhibitions including Women’s Work. Her research on the history of child care has been published in journals such as Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society and featured in popular outlets including the New York Times, Washington Post, and PBS NewsHour. Jeanne Gutierrez is Curatorial Scholar in Women’s History, New-York Historical Society, and was a curator on the Women's Work exhibition.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Anna Danziger Halperin and Jeanne Gutierrez / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com