The good news about inflation in recent months is that it’s slowing, but that probably doesn’t matter much to the American consumer; slowing inflation still means that prices are rising. The cost of groceries ticked up just 0.3% from the previous month in January, but has grown 28% since January 2019. No wonder Americans still get sticker shock when they look at their grocery bills.

It may seem contrary that prices are still rising when so many of the events that kicked off the high inflation of recent years—the COVID-19 pandemic, the resulting supply chain headaches, the war in Ukraine—started years ago. But there are dozens of different factors that go into food inflation.

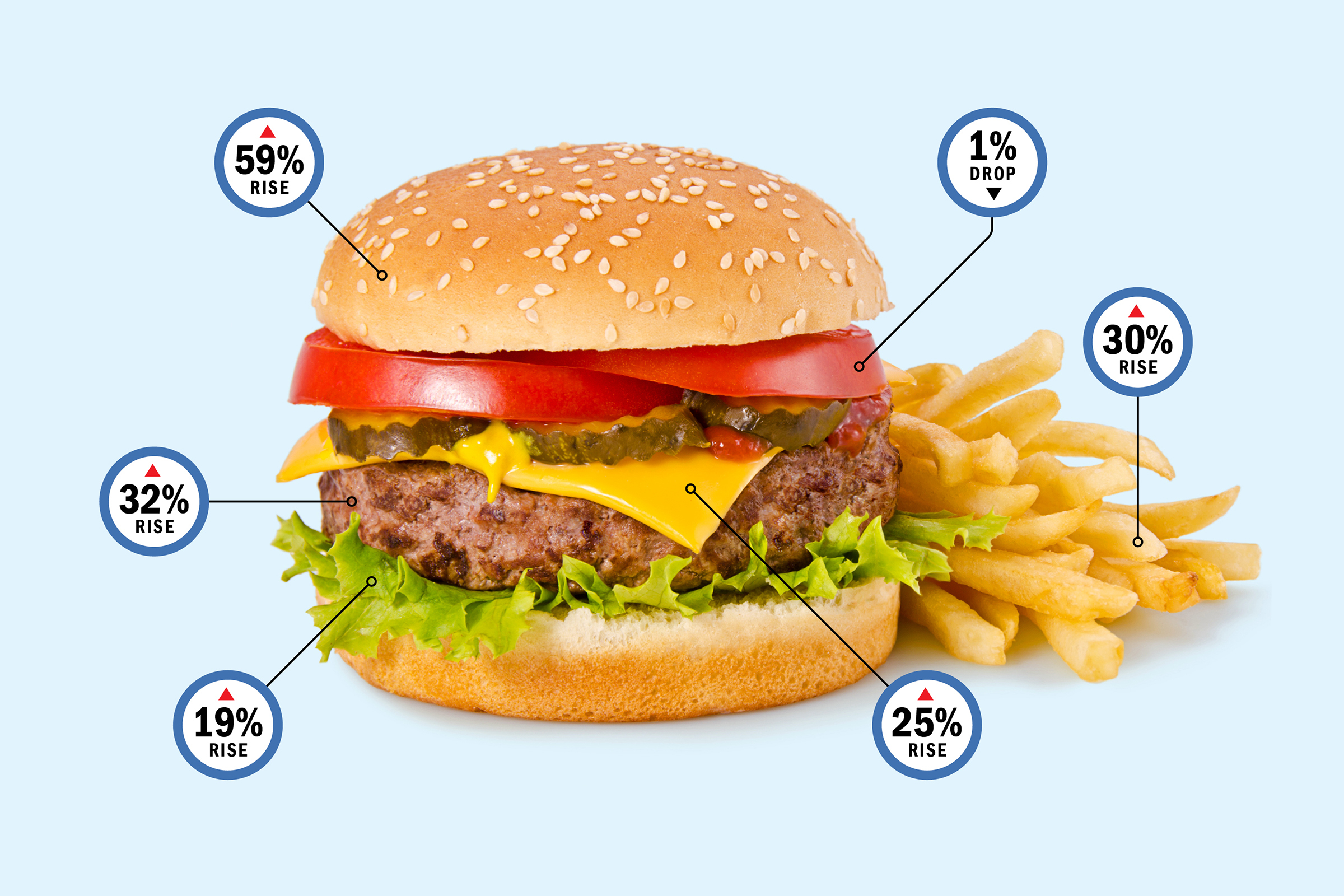

To explain these factors, TIME picked a meal that might be typically consumed by an American household—a cheeseburger and fries—and looked at what’s driving prices higher for different ingredients. We found that the cost of ingredients for a cheeseburger and fries—$4.69—is roughly a dollar more than in 2019, though just pennies from a year ago.

Wells Fargo chief agricultural economist Michael Swanson explains the factors driving up prices bite by bite:

White bread: Up 59% since 2019

Bread is one of the items that jumped the most in price since the beginning of the pandemic. The dollar figure isn’t much—a pound of white bread costs $2.03 now, up from $1.27 in January 2019, according to government data. What happened? Bread was really cheap for a long time, Swanson says. The price was so low that it essentially fell from 2014 to 2019, as cheap wheat and robust bakery competition forced bread makers to lower prices. The bread business was so tough that many bakeries went out of business or consolidated.

Prices started rising at the beginning of the pandemic, but really jumped in early 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine and the price of wheat spiked. The price of wheat has since cratered, but the Russian war gave producers an excuse to increase prices. For years, bakeries really needed the price of bread to go up to cover their labor, energy, and transportation costs, and finally, they had the opportunity. “Once the dam broke, it was going to be quite awhile for the inflation to go back down,” Swanson says.

Processed cheese: Up 25% since 2019.

In 2022, the price of milk was too low for farmers to make money, so they started culling their herds; cheese buyers, anticipating that there would be a shortage of cheese, started “leapfrogging each other to get supplies purchased,” Swanson says. That drove cheese prices up to their peak in April 2022. The same thing may be happening now, he says; a recent milk production report showed heavy signs of culling.

Even if the price of cheese drops on commodities markets, it can take awhile for consumers to feel the difference. When cheese prices skyrocketed in 2022, retailers couldn’t raise prices that much, Swanson says. So when cheese prices fell back down, retailers tried to recover what they had lost. The price of processed cheese is still 25% above what it was in January 2019.

Ground beef: Up 32% since 2019

In the beginning of 2024, there were only 87.2 million cattle and calves in the United States. That may seem like a lot of cows—roughly one for every four people in the U.S., but that number actually represents the lowest inventory since 1951. Fewer cows means higher prices for the ones that are getting sold and turned into meat.

U.S. herds are at such low levels primarily because of drought and high supply costs. In the last four years, as drought plagued Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and other cattle-raising regions, farmers found that it was costing a lot of money to feed their cows. They started selling them—and, unusually, they also sold female cows, who would typically have been held back for breeding, according to economists from the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Now, El Nino has brought moisture to much of the U.S., and farmers are trying to rebuild their herds. But doing so will be expensive, keeping the cost of beef high. While the U.S. had a record corn crop in 2023 and prices of feed are falling, some farmers are holding back cows they otherwise would have sold in order to rebuild their herds. With higher interest rates for borrowing and more expensive cows, beef prices aren’t likely going anywhere soon. In February, economists from the American Farm Bureau Federation predicted that 2024 would be characterized by record-high beef prices in the grocery store.

Tomatoes: Down 1% from 2019

One of the only foods that have not experienced major price increases over the past four years. That’s in part because they were already expensive compared to other fruits and vegetables. But tomato prices are also affected by trade rules; ever since 2013, U.S. and Mexican producers have essentially agreed to set the price of tomatoes so one country’s farmers don’t have an advantage over another.

Potatoes: Up 30% from 2019

Potato crops in 2021 and 2022 were severely affected by drought and wildfire smoke, reducing yields. With fewer potatoes in the U.S. and abroad, prices jumped. In 2023, though, U.S. potato production increased for the first time in seven years, which should temper prices.

Romaine Lettuce: Up 19% from 2019

An insect-born virus destroyed huge swaths of lettuce crops in California in 2022, causing costs to spike. The price has fallen since then, but labor and transportation costs are still higher than in 2019, which means suppliers aren’t rushing to bring down prices further.

You Won't Save Money Dining Out

Your restaurant burger is probably going to get more expensive, too, as wages continue to rise in a competitive job market. “Across the board, everything is just up,” says Brian Arnoff, the co-owner of Meyer’s Old Dutch, a hamburger restaurant in Beacon, N.Y., his restaurant has done two pricing increases since the pandemic, its burger now costs $16, up from $13 in 2019.

Read More: How Much Should You Tip? 5 People Share Their Habits

For restaurants, though, labor accounts for much of the increased cost of food. Meyer’s Old Dutch can’t even get applicants to come to interviews unless he offers $18 an hour, significantly higher than the state minimum wage of $15 an hour. Wages across his business have climbed as he tries to retain talent; cooks who made $18 an hour in 2019 are now starting at $20. Until the pandemic, Arnoff says, the cost of food and other supplies surpassed the cost of labor. Now, he spends more on labor than on ingredients.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com