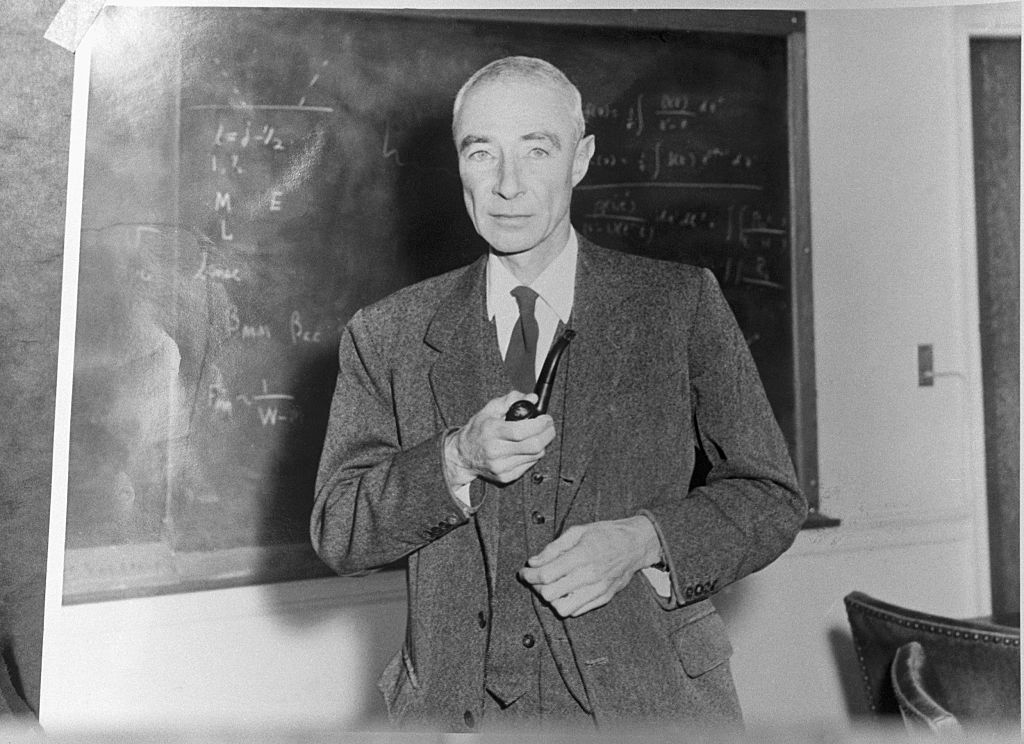

Christopher Nolan’s biopic of the father of the atomic bomb has been a cultural triumph. Besides its artistic achievements—it has racked up awards and shined again at last night’s Oscars—the film touched a deep nerve in society and reignited public conversations around nuclear risks that we’ve not seen since the end of the Cold War.

People who saw the film were rightly shaken by its vivid depiction of the bomb’s awesome destructive power. Many have commented on the existential dread the film induced. But what’s been largely overlooked in discourse around the film are the urgent, powerful, and specific lessons the film—and its protagonist J. Robert Oppenheimer—have for the world today.

As inheritors of Oppenheimer’s legacy, we feel an urgent need to speak out in face of surging nuclear risks. We cannot afford to repeat the mistakes made by politicians at the start of the atomic age to ignore Oppenheimer’s warnings and dive headlong into another dangerous and futile nuclear arms race. As the U.S. prepares to spend close to $2 trillion on remaking its nuclear arsenal, we must draw on Oppenheimer’s wisdom and take bold action now to protect humanity from the existential threat of nuclear weapons.

More From TIME

The Oval Office scene from the film between Oppenheimer, Truman, and Secretary of State James Byrnes carries profound meaning. It reflects a real meeting that perfectly encapsulates the conflict between two starkly different visions of not only how to manage the atom, but also of how nations should fundamentally relate to each other in a new world rising from the ashes of the old.

On one side, Oppenheimer, joined by other Manhattan Project scientists and Secretary of War Henry Stimson, understood that other advanced nations were bound to soon discover the so-called “secrets” of the atomic bomb. They knew that, unless the U.S. gave up its nuclear monopoly and established a cooperative international body to make sure that the atom would only be used peacefully, others—chiefly the Soviet Union—would feel compelled to develop their own bomb to restore the balance of power. A free-for-all arms race between powerful industrial nations over the most destructive weapon in human history would make the world exponentially more dangerous and ultimately be a dead end. Only mutual accommodation and good-faith cooperation could guarantee peace and advance the common interests of humanity.

On the other side, however, figures like Byrnes held that the U.S. can and should hold onto its monopoly over the bomb. Fruitful wartime partnership notwithstanding, they fundamentally distrusted the Soviet Union, believing that the Soviets only understood raw power, of which the bomb was the highest representation. Peace could only be achieved through military strength, and relations between rivals must be zero-sum.

Read More: Here’s How Faithfully 'Oppenheimer' Captures Its Subject’s Real Life

Initially, Truman entertained Oppenheimer’s disarmament proposal conceived on the principles of mutuality, openness, and bold U.S. leadership. Known as the Acheson-Lilienthal Plan, it called for the U.S. to give up its nuclear monopoly, reveal what it knew to the Soviets, and establish an international regime that would control all fissile materials and forbid any additional nuclear weapons development.

While mindful of the danger of nuclear weapons, Truman was ultimately more sympathetic to Byrnes’ views, dismissing Oppenheimer’s pleas for speedy nuclear disarmament. His eventual offer to the Soviets, known as the Baruch Plan, insisted on unilaterally retaining U.S. nukes until the U.S. was satisfied with other nations’ compliance with nonproliferation, as well as unrestricted ability to inspect and punish the Soviet Union for any perceived or real violations.

Though the Soviets committed to nuclear disarmament in principle, they felt that Truman’s plan was too one-sided and feared that it was a cover for the U.S. to maintain its nuclear monopoly. As expected, they ultimately rejected the Baruch Plan and developed their own bomb. Thus began the Cold War arms race—conceived on naive and false hopes instead of science that the U.S. could keep nuclear weapons a secret, and that producing more of them faster would make Americans safer—that saw, at its peak, almost 70,000 nuclear weapons.

After the many crises and terrifying near misses that followed—and numerous unheralded casualties from nuclear weapons construction and testing—leaders of the U.S. and the Soviet Union eventually stepped back from the brink and made concerted efforts to de-escalate tensions. Successive arms control breakthroughs saw dramatic mutual reductions of stockpiles, elimination of whole classes of weapons, banning of nuclear testing, and promises to eventually abolish nuclear weapons.

Yet today, that hard-won arms control consensus has all but collapsed. From Ukraine to the Korean Peninsula to the Taiwan Strait, the horrific prospect of nuclear use has once more reared its ugly head. Leaders have seemingly forgotten about the terrifying consequences of the Cold War, while citizens—many of whom came of age in a world where nuclear risks became an afterthought—have largely given their governments free reign to launch a new nuclear arms race.

While there are immediate steps the President can and should take to restart arms control diplomacy, we believe that any lasting solution to today’s nuclear perils requires reimagining our foundational assumptions around global security. Oppenheimer correctly understood that, to secure the Soviet Union’s buy-in on disarmament, the U.S. must lead by example and offer a plan that addresses its rival’s insecurity. He believed in diplomacy, mutual accommodation, and the potential for even rivals to come together around shared interests. Those ideas were as difficult to swallow then as they are today, but he was and remains right. Initially dismissed as naive, he was ironically vindicated by the concrete outcomes of later U.S.-Soviet arms control cooperation.

We must take his insights to heart and apply them to today’s volatile tripolar nuclear rivalry between the U.S., Russia, and increasingly China. While some urge “strategic competition” between the three powers, declaring that geopolitical flashpoints like Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine preclude any potential for deal-making, we believe that now, as at the height of the Cold War, is precisely the time for the three countries to come to the table. Their mutual self-interests, and the collective survival of humanity and the planet demand it.

Read More: Nuclear Energy’s Moment Has Come

Our political leaders must marshal the courage and vision to overcome their differences, build a new global security architecture fit for our increasingly multipolar world, and move quickly to halt the new nuclear arms race and build a new consensus on arms control and disarmament. The alternative is sliding back down the abyss of nuclear brinkmanship and existential terror of the darkest days of the Cold War.

The start of the atomic age was defined by a costly, dangerous, and ultimately futile nuclear arms race that repeatedly brought the world to the brink of destruction. But it did not have to be that way. Oppenheimer and others offered an alternative path that holds important lessons for us today as global nuclear risks rebound. We must learn those lessons, avoid repeating the mistakes from the Cold War, and stop the budding new nuclear arms race before it’s too late.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com