No one in human history has ever seen an eclipse quite like the one seen by the crew of Apollo 12 on Nov. 21, 1969. Countless billions of us have seen the moon eclipse the sun, casting its shadow on the Earth; countless billions have seen the Earth similarly block solar light, casting a shadow on the moon. But the Earth eclipsing the sun, as viewed from far off in deep space? That’s a different matter—but it’s precisely what the astronauts bore witness to when they were on their way back to Earth after having stuck history’s second crewed lunar landing, in the moon’s Ocean of Storms, two days earlier.

“We’re getting a spectacular view,” radioed command module pilot Richard Gordon as the sun appeared to vanish behind the Earth. “It’s unbelievable.”

“Fantastic sight,” added lunar module pilot Al Bean. “The sun is almost completely eclipsed now and what it’s done is illuminated the entire atmosphere all the way around the Earth.”

“Looks quite a bit different than when you see the moon eclipse the sun,” added Gordon.

It will be a long while before humans witness the same spectacle again—sometime in the future when astronauts travel moonward again. But no one has to wait terribly long to see another, equally stunning cosmic spectacle. On April 8 the moon will pass in front of the sun creating a total solar eclipse—the first one to touch the lower 48 U.S. states since 2017, and the last one that will cross Canada and the U.S. until 2044.

Read more: How to See the First Solar Eclipse of 2024

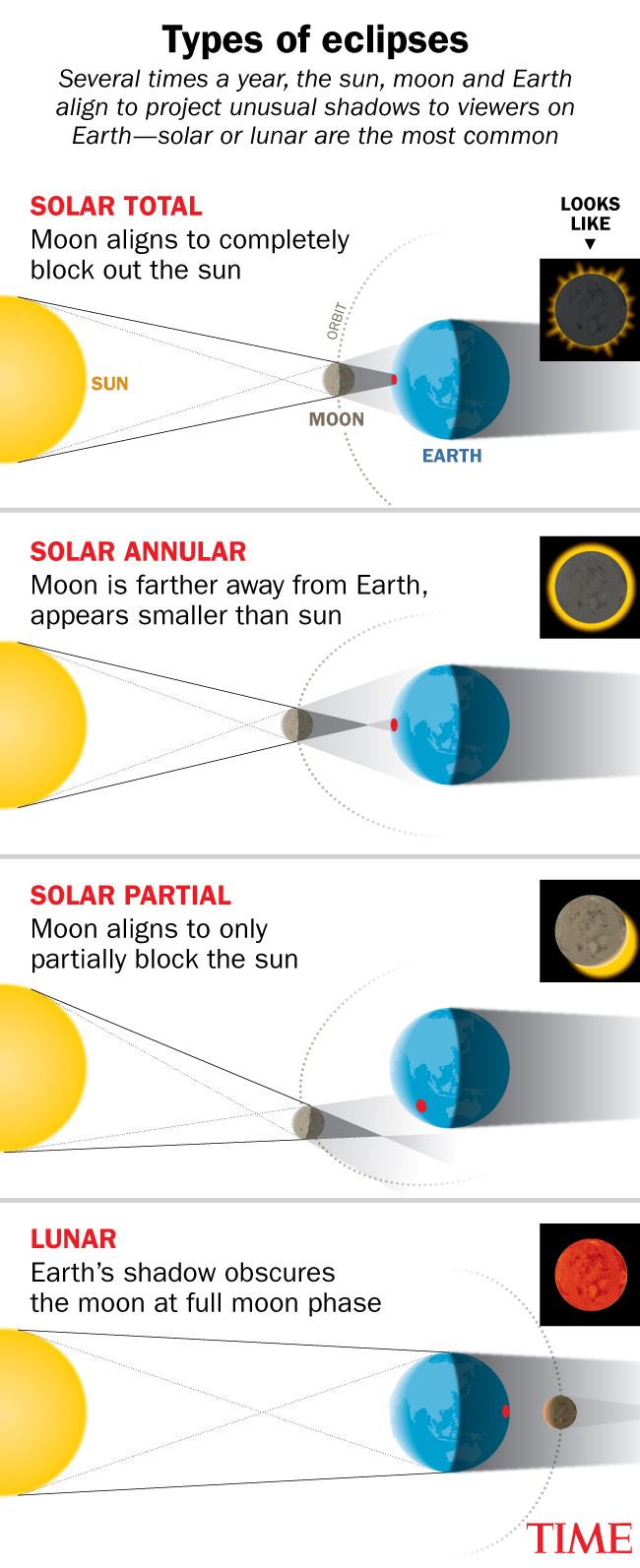

The upcoming sky show is only one variety of solar eclipse. Total solar eclipses happen once every 18 months somewhere in the world—and they’re far and away the most gobsmacking type. That’s owed partly to a wonderful bit of cosmic serendipity: the sun is about 400 times larger than the moon, but it’s also about 400 times more distant, meaning that the two disks appear almost precisely the same size when they’re hanging in our sky. On those rare occasions when the moon passes directly in front of the sun, it thus fully blocks the solar disk, blacking it out completely and leaving only the sun’s corona—or crown—of flames visible.

Why Aren’t There More Total Eclipses?

But why exactly are those occasions so rare? Once every month, the moon passes between the Earth and the sun, so it would seem that once every month we’d get an eclipse. That’s not the case because the moon’s orbit around the Earth is tilted by about five degrees relative to the equator—just enough of an inclination to make it appear to pass above or below the sun on its monthly passage. Only on those rare occasions when the moon passes the sun at a precise equatorial angle do we get a solar eclipse—and even then it’s not always total. Spectators at different spots on the ground will witness the sun-moon dance from different perspectives, meaning that for most of them the moon will merely take a bite of the sun, leaving it as a crescent in the sky.

Read more: Where You Can Watch the Solar Eclipse

The path of totality is a narrow one: on April 8 it will trace a band just 185 km (115 mi.) wide, as the sun crosses the country from Texas to New England. Viewers outside of that track will see the sun eclipsed to different extents—by 94% in Chicago, 90% in New York City, 56% in Denver, 49% in Los Angeles, and less and less the farther and farther away a viewer moves. On the whole, only about 31 million lucky Americans live in the path of totality.

Annular Eclipses

Even when the moon does cross in front of the sun at precisely the right equatorial point, a total eclipse is not guaranteed. That’s because the moon’s orbit around the Earth is not perfectly round, but instead elliptical—ranging from a so-called apogee of about 405,000 km (252,000 mi.), the farthest distance from the Earth, to the closer perigee of 360,000 km (224,000 mi). A moon at or approaching apogee appears too small to block the sun entirely, creating what is known as an annular eclipse—one that is much less spectacular than a total eclipse since the solar light leaking out from around the moon largely washes out the view of the lunar disk. Annular eclipses occur once every two years.

Lunar Eclipses

Lunar eclipses—when the Earth moves between the sun and the moon, casting a shadow on the moon’s surface—are less spectacular than solar eclipses, but still dramatic, as much of the moon slowly seems to vanish in the sky. Here, too, the moon’s five-degree inclination around the Earth prevents an eclipse from happening once a month when the Earth is in the path of the sun’s light that would otherwise be shining on the moon. On average lunar eclipses happen just one or two times a year.

Other Eclipses in Space

Throughout the solar system, and indeed the cosmos as a whole, eclipses happen all the time—whenever a foreground body moves in front of a background body. Both Earth-based and ground-based telescopes use this so-called transit model to detect planets orbiting other stars. They do so by measuring the vanishingly small dimming that occurs when the planet passes in front of the star and obstructs a tiny bit of its light.

Moons orbiting our solar system’s planets also create their own eclipses, but the shadow a satellite like Jupiter’s 3,100 km- (1,940 mi)-diameter moon Europa casts on its parent world’s 142,800 km- (86,900 mi)-wide bulk is too small to see without a powerful telescope.

Earth is alone in the solar system not just in having a moon uniquely sized and situated to create as dazzling a phenomenon as a perfectly total solar eclipse, but also in being home to smart and sentient creatures who can understand and appreciate what they’re seeing. If you don’t live in the path of totality it’s worth trying to get there to be among the fortunate few who will have that rare experience.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com