Men have played golf on the moon. Images transmitted from the surface of Mars have become utterly commonplace. The Hubble Space Telescope can see 10 billion to 15 billion light-years into the universe.

But a mere three miles under the sea? That’s a true twilight zone.

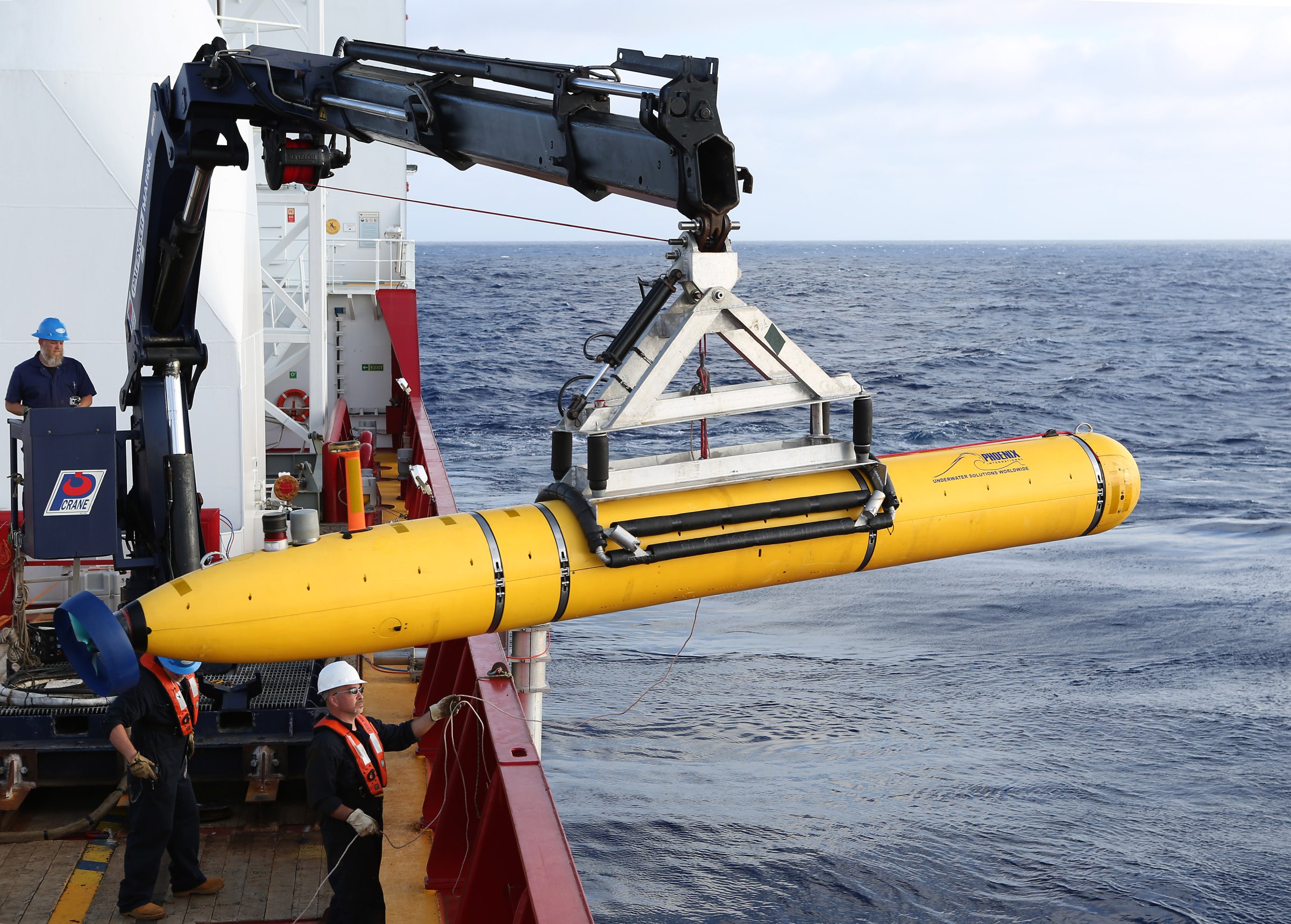

As the hunt for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 demonstrates, at that depth — minuscule compared with the vastness of space — everything is a virtual unknown. A high-tech unmanned underwater submarine, Bluefin-21, has been dispatched four times to look for wreckage from the jet, but the crushing water pressure and impenetrability of this void mean that only its most recent pair of missions were completed. Scrutinizing dust and rock particles on the Red Planet, tens of millions of miles away, is a breeze. Understanding what’s on the seafloor of our own planet is not.

About 95% of deep ocean floor remains unmapped, but that’s almost certainly where the most sought after aircraft in history is going to be found. “Our knowledge of the detailed ocean floor is very, very sparse,” Erik van Sebille, an oceanographer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, tells TIME.

The reason for our ignorance is simple. Virtually all modern communications technology — be it light, radio, X-rays, wi-fi — is a form of electromagnetic radiation, which seawater just loves to suck up. “The only thing that does travel [underwater] is sound,” says van Sebille, “and that’s why we have to use sonar.”

Sound is formed by mechanical waves and so can penetrate denser mediums like liquids: but at a 3-mile (5 km) depth, even sonar starts to have problems establishing basic parameters. The waters in which the search for MH 370 is happening, for example, were thought to be between 13,800 and 14,400 ft. (4,200 and 4,400 m) deep, because that’s what it said on the charts that had been drawn up over time by passing ships with sonar capabilities. It turns out those seas are at least 14,800 ft. (4,500 m) deep. We only know that now because that’s the depth at which Bluefin-21 will automatically resurface — as it did on its maiden foray — when onboard sensors tell it that it’s way, way out of its operating depth. The problems with Bluefin-21, van Sebille says, show us that “even our best maps are really not good here.”

The other issue affecting visibility is the sheer volume of junk in the ocean. About 5.25 trillion particles of plastic trash presently billow around the planet, say experts, weighing half a million tons. There are five huge garbage patches in the world’s seas, where the swirling of currents makes the mostly plastic debris accumulate. The largest of these is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a gyre measuring an estimated 270,000 to 5.8 million sq. mi. (700,000 to 15 million sq km). This refuse gets ingested by plankton, fish, birds and larger marine mammals, imperiling our entire ecosystem.

Flotsam debris has already impeded the hunt for MH 370. Hundreds of suspicious items spotted by satellite have sent aircraft and ships on hugely costly detours to investigate what turned out to be trash. (On Friday an air-and-surface search continued, with 12 aircraft and 11 ships scouring an area of some 20,000 sq. mi. [52,000 sq km] about 1,200 miles [2,000 km] northwest of Perth.) Officials are saying that such efforts are becoming futile.

For all we know, Bluefin-21 could also be confused by the sheer volume of garbage down there. According to a study by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute published last June, based on 8,000 hours of underwater video, an unbelievable quantity of waste is strewn across the ocean floor. A third of the debris is thought to be plastic — bags, bottles, pellets, crates — but there is a vast amount of metal trash as well, including many of the 10,000 shipping containers estimated to be lost each year.

“I was surprised that we saw so much trash in deeper water,” said Kyra Schlining, lead author on the study. “We don’t usually think of our daily activities as affecting life two miles deep in the ocean.”

That’s because we can’t see it. It’s tempting to say that MH 370 might as well have vanished into space — only if it had, we’d have found it by now.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com