There is a moment during Bill Moyers 1982 interview with Garry Winogrand when Winogrand, wandering through the streets of Los Angeles, lifts his camera to set up a shot. It’s a move he surely performs often, but this time something doesn’t quite work: He clicks, but speedily pulls the lens away from his face, shrugging his shoulders.

“What’s happening?” a woman sitting outside a nearby restaurant asks, seeming to take notice of Winogrand as he hesitates, and of the documentary crew with him. “I’m surviving!” he replies in his thick Bronx accent, laughing warmly.

The public television piece – originally broadcast on New Jersey’s WNET – is but a very brief window into a moment in his life, and yet we learn something crucial about him. Humble, genial, this is Winogrand as he is most often remembered; wandering through city streets with a Leica over his shoulder. But here we also see him mid-process, engaged with the world around him, unafraid of taking risks.

“I learned a long time ago to trust my instincts,” Winogrand tells Moyers a little later. “You see? You don’t learn anything from repeating what you know.”

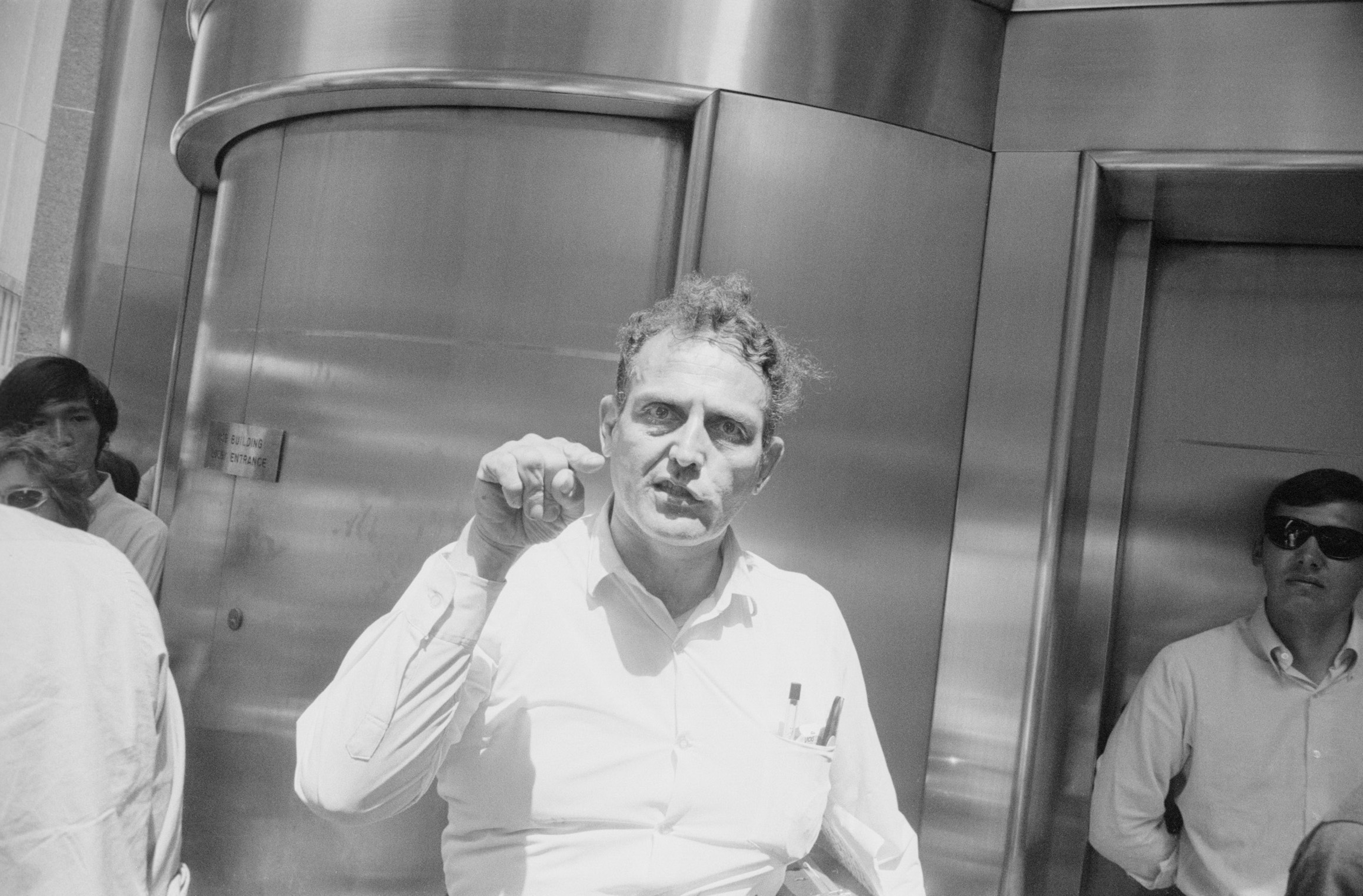

Born in the Bronx in 1928, Winogrand certainly did well to trust his instincts. A deeply unpretentious and inventive photographer, his frenetic, apparently off-the-cuff pictures descend from the tradition of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans. On the streets, he was a shoot-often kind of guy, one who could get so close to subjects as to either charm or irritate them. Winogrand took so many pictures, in fact, that it is hard to grasp the breadth of his contribution to photography: After his death in 1984 he left behind an estimated 250,000 frames in total, most of which he never saw himself.

It is into these unknown frames that a retrospective organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the National Gallery of Art in Washington attempts to delve. Aiming to expose more of his work, and to show that he was not simply a street photographer, what emerges from a carefully curated selection is not just a portrait of one of the country’s most prolific artists, but of one of the most important photographers of the 20th century. One who chronicled all American life.

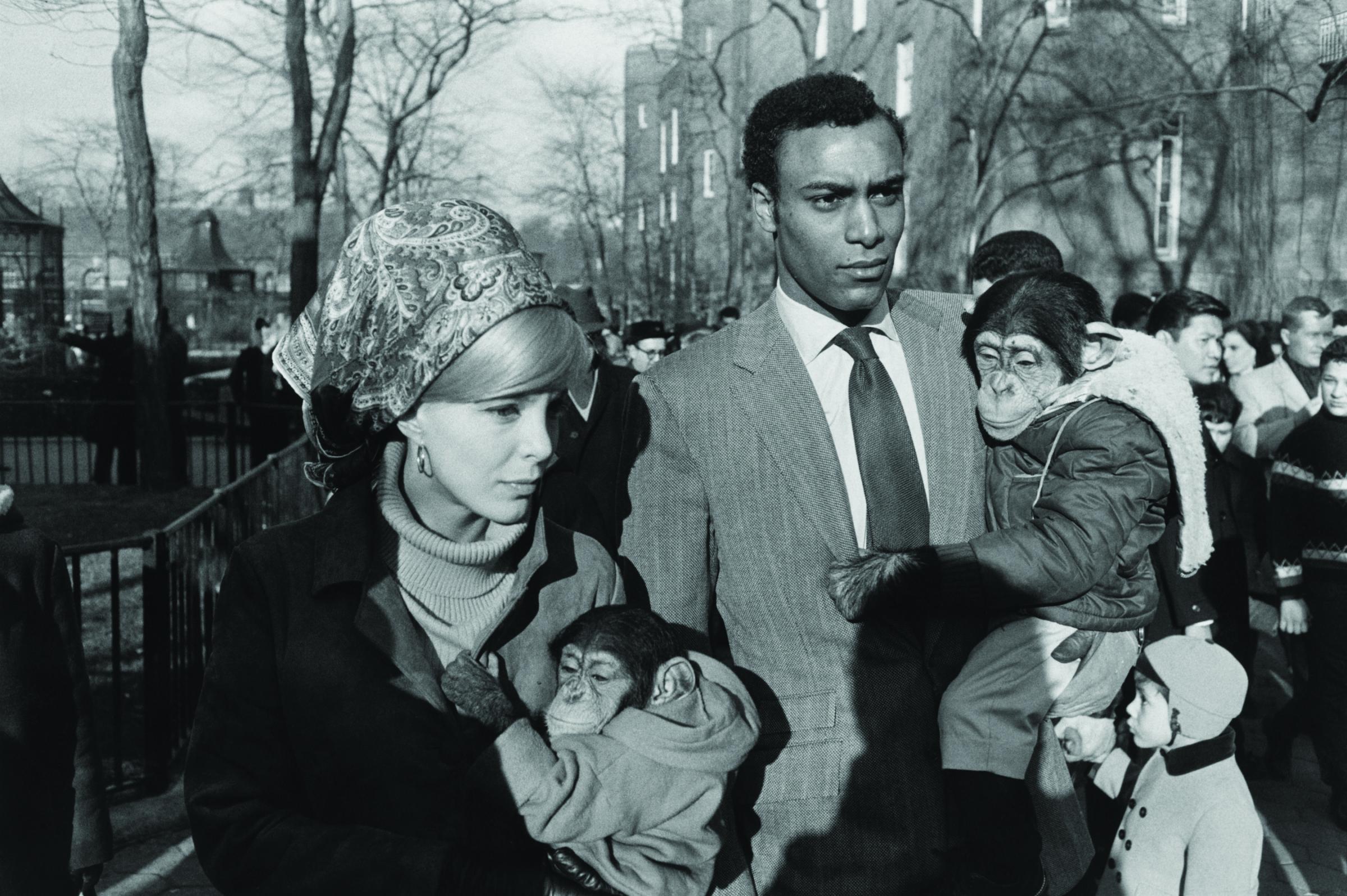

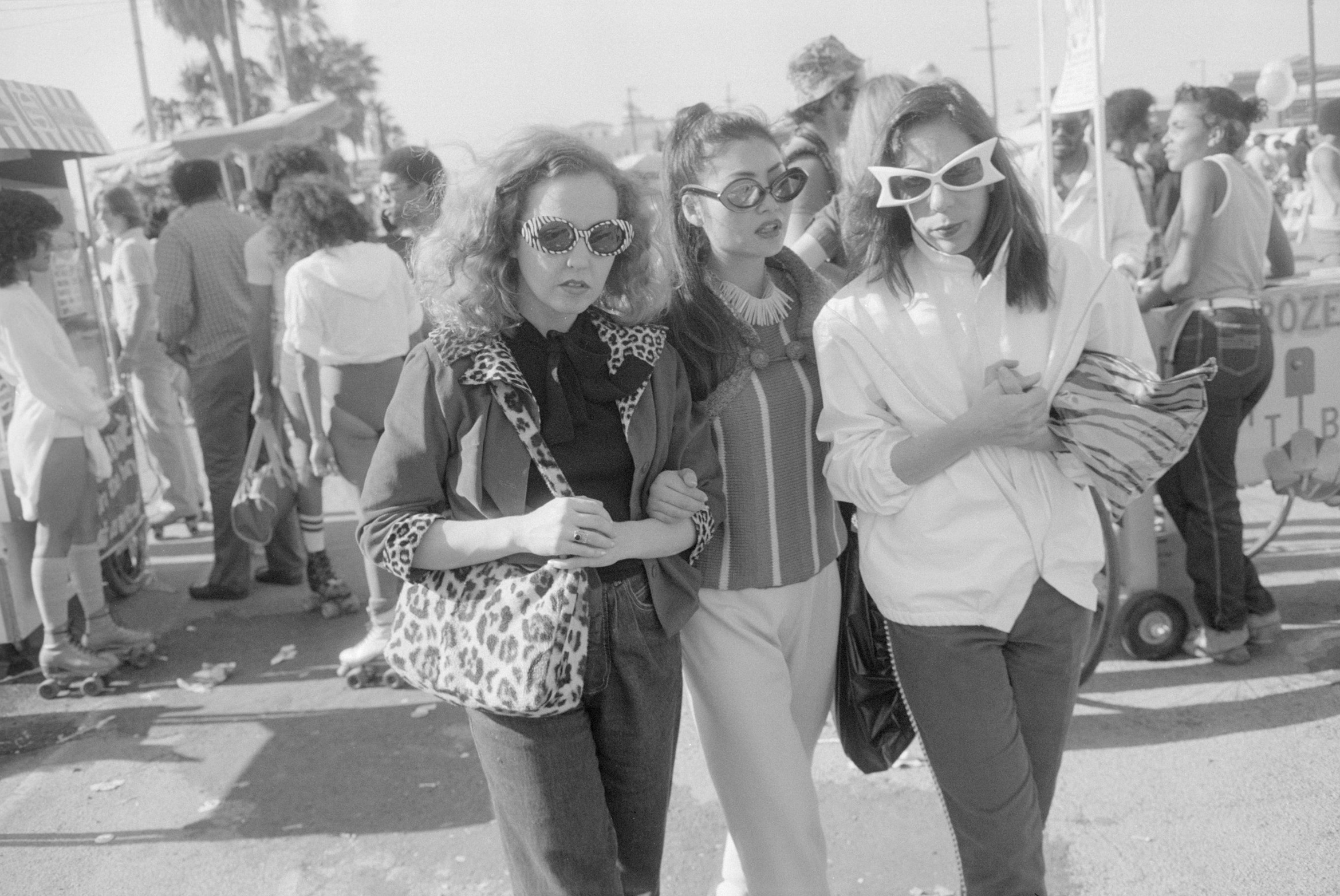

“We see a whole range of people,” says Leo Rubinfien, photographer and guest curator of the show. “Here’s the businessman, here’s the beauty, and here’s the cowboy. Winogrand really offers an epic picture of life in the United States.”

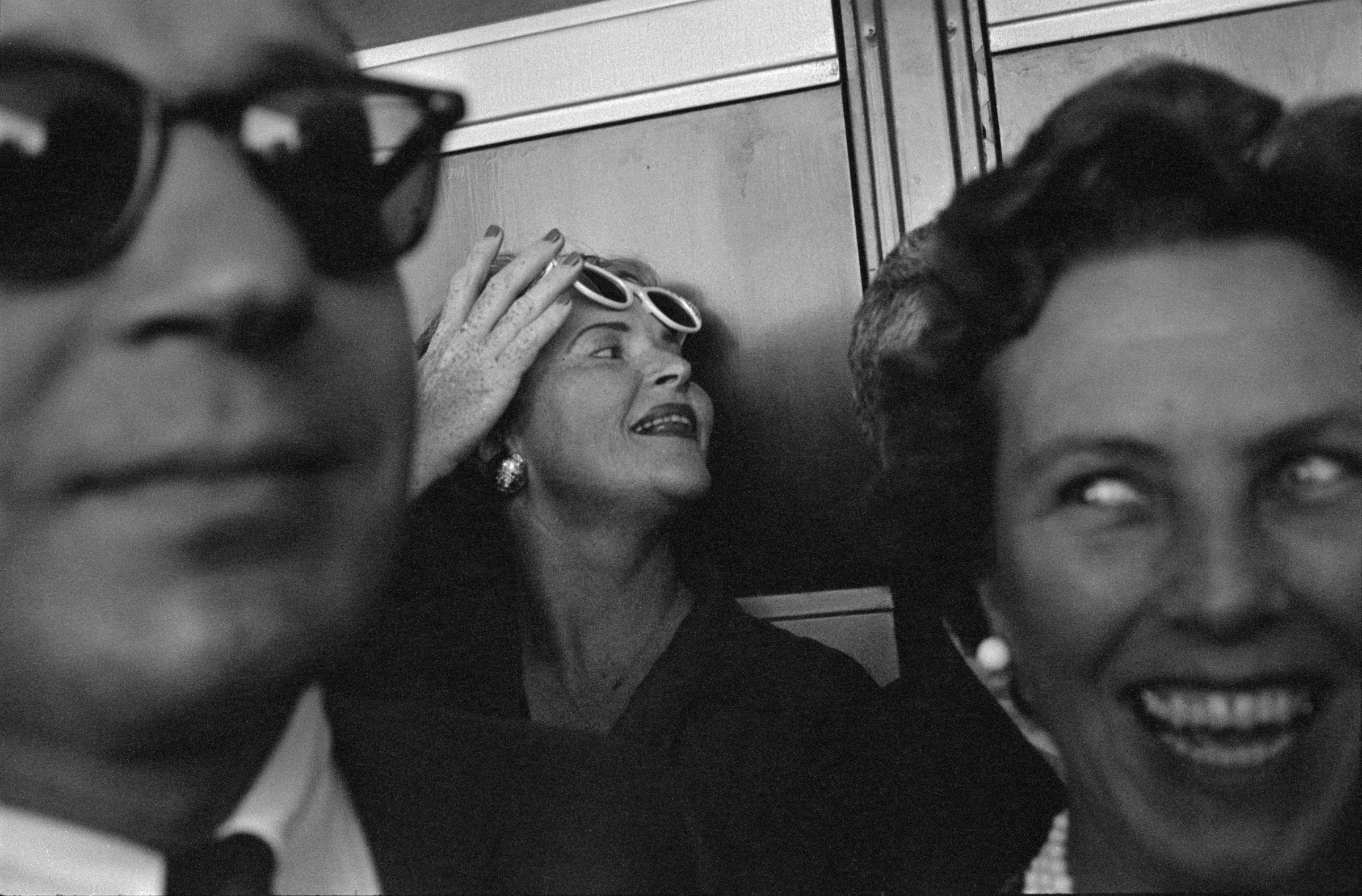

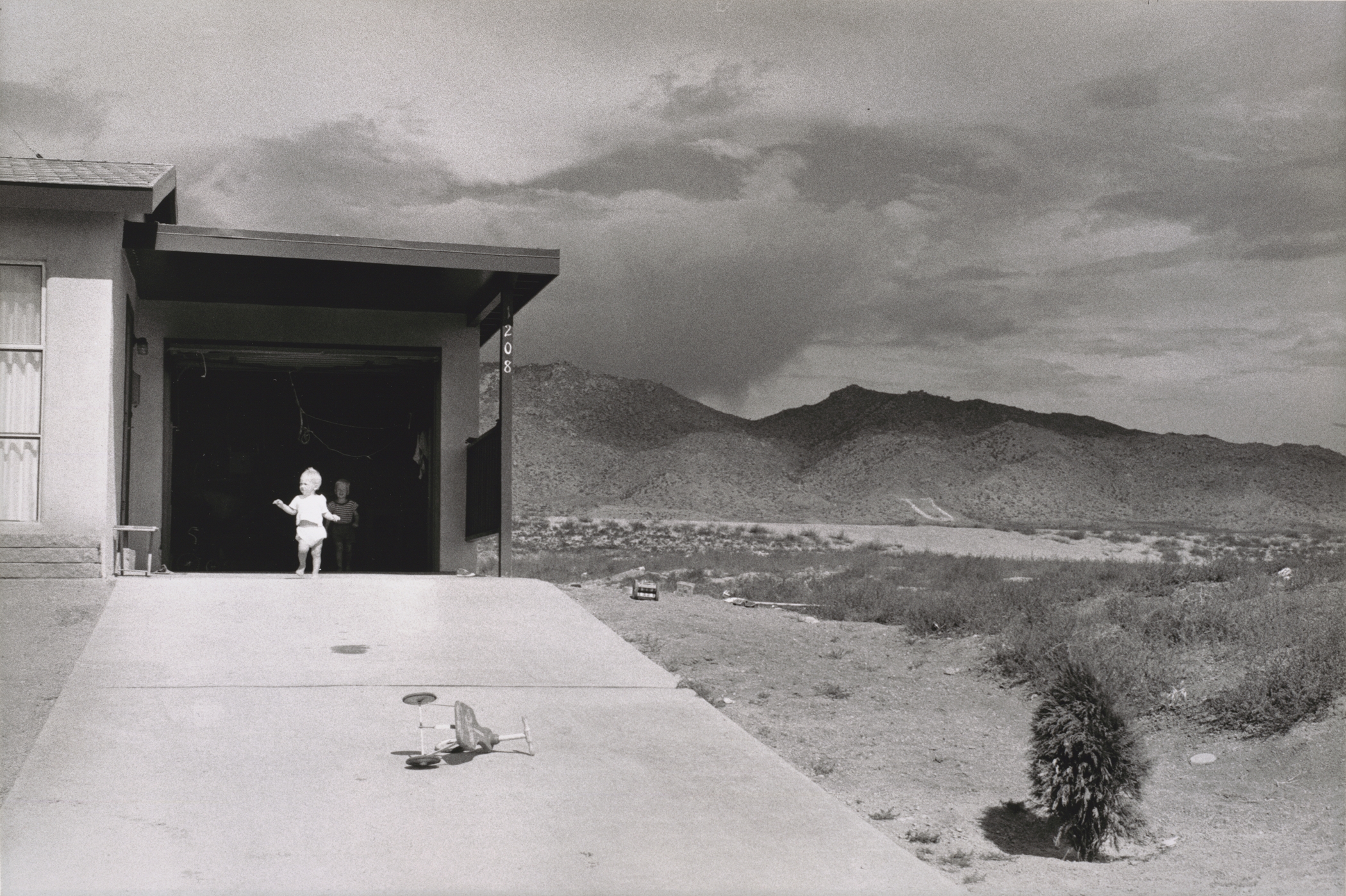

Indeed, from the sparse, big-skied domesticity of the family home in Albuquerque, 1957 to the awe-struck kid eying jewelry in Fort Worth, Texas, 1974–77 and from the sneaking, lighthearted voyeurism of a captured kiss in New York, 1969 to the bubbly, near-ecstatic intimacy of the women in Democratic National Convention, Los Angeles, 1960, to know Winogrand’s work is surely to know the soul of America.

And yet if Winogrand authored a modern epic, what is equally striking was his acknowledgment of the limits of photography throughout his career. As a documentarian of the everyday, he believed his pictures were mere windows into a moment, at best a surface level description of life. Indeed, he rallied against photojournalism. Or at least photojournalism as it operated in his day. Shooting at a time when many magazines would commission photographic projects that were often editor-directed and subservient to the written stories accompanying them, he preferred to shoot from the gut. Working not from top down, but from the bottom up. Just as life presented itself to him.

“Winogrand was a student of America,” Rubinfien adds. One who constantly asked the question: “What is it that makes us us?”

Garry Winogrand runs at SFMOMA from March 9, 2013 to June 2, 2013. A catalog, published by Yale in association with SFMOMA, accompanies the show.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com