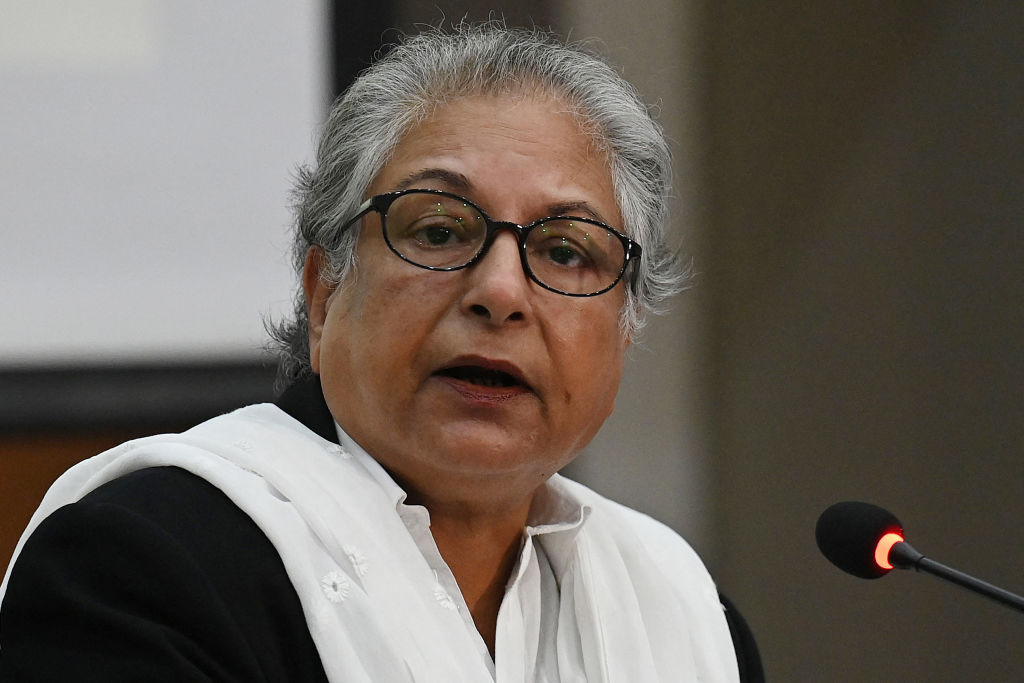

Hina Jilani, a leading human rights lawyer and pro-democracy activist from Pakistan, acutely recognizes the power of the military in deciding the fate of her country’s elections. “The military has the unique tendency of not doing the right thing by interfering in politics,” she tells TIME.

In the recent elections held on Feb. 8, the military did so by throwing former Prime Minister Imran Khan in prison and barring his party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), from campaigning. It also suspended the internet across the country and attempted to keep Khan’s supporters away from the ballot box. But in a stunning—and controversial—election result, PTI ended up winning just over a third of the 265 seats. There was a political limbo. To end it, PTI’s rival parties, the military-backed Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN), led by former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), agreed to form a coalition; now, Sharif plans to nominate his brother Shehbaz Sharif to be prime minister.

Observers say PTI’s success, which defied all odds, has sent a strong message from an angry Pakistani public: they are tired of the military brazenly orchestrating the vote. But Jilani, who has championed democracy for nearly four decades, remains cautious.

“Things are still very fluid post-election, and that in itself shows how this period is not going to be a very stable one,” she says.

As a co-founder of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HCRP), the country’s leading independent human rights organization and trusted elections watchdog, she says an election marred by irregularities can usually signal what’s to come. “Because it was a very close election and nobody got a majority, the stage we are at today does not favor any hope or stability for Pakistan,” she laments.

Today, the 70-year-old is recognized the world over for her pro-democracy and human rights advocacy. In 2000, she was appointed the United Nations’ first special representative of the Secretary-General on human rights defenders, where she led a 2006 inquiry on Darfur. Three years later, she was appointed to the UN’s fact-finding mission on the Gaza conflict, followed by co-chairing the World Health Organization’s high-level working group on the health and human rights of women and children. In 2001, she was awarded the Millennium Peace Prize for Women, and in 2013, she joined The Elders, a group of independent leaders founded by Nelson Mandela to amplify “the voice of the voiceless.” Today, she also serves as co-chair of the International Task Force on Justice.

As a teenager in her birth city of Lahore, Jilani often saw her father thrown behind bars because of his “aversion to working under a military government,” she says, which at the time was led by former president Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. “We experienced what it was like to have no democratic or fundamental rights in a country under the dictatorship of the military,” she says, “and I began to understand what sacrifices are demanded of you in Pakistan’s politics and as a democratic rights activist.”

Under Zia-al-Huq, Jilani also noticed that more and more women were being imprisoned because of “so-called Islamic laws that were very much against the rights of women and non-Muslim minorities,” she says. This realization spurred her and her sister Asma Jahangir, another celebrated human rights lawyer, to start a platform called the Women’s Action Forum. “While we accepted there are realities in this country, both social and political, we convinced ourselves and others that we were in the business of changing them,” she says.

Read More: Pakistan’s Military Used Every Trick to Sideline Imran Khan—and Failed. Now What?

It was dangerous territory to veer into, Jilani acknowledges, especially when reflecting on a case that defined her career—and perhaps her life. In April 1999, a 28-year-old woman named Samia Sarwar traveled to Lahore to meet Jilani to seek legal advice on how to divorce her abusive husband. Sarwar’s husband had pushed her down the stairs while she was pregnant, and she was convinced that her life was in danger at her own parents' home in Peshawar. She took refuge at Dastak, a women’s shelter established by Jilani as part of the country’s first all-women law firm and legal aid center. But a few days later, Sarwar’s mother arrived at Jilani’s office with an assassin who, in a moment that shocked the nation, shot Sarwar in the head. He also aimed at—but narrowly missed—Jilani.

No one was arrested or punished for Sarwar’s murder, but the case led to heightened scrutiny around the issue of “honor killings” for the first time in Pakistan. “Women were protesting and appeared before the Senate, insisting that the law needs to change,” says Jilani. Before long, not only was legislation put into place to try and deter such crimes, but there was also a public recognition that honor killings cannot be justified by religion or culture. Though the practice continues even today due to a lack of legal enforcement—2022 alone saw 384 honor killings reported, according to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan—“at least we have legal tools that we can use to stand up and fight for justice,” she says.

Since then, Jilani has survived many threats “both open and covert.” But she insists, “I've never really been afraid of anything, not because I have courage, but because I have no other option.”

In 1987, Jilani and her sister also co-founded the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HCRP), the country’s leading independent human rights organization. “A group of lawyers, including myself, felt that we needed a human rights organization in this country that was independent and able to speak truth to power in a country where there was interference in the democratic process in particular,” she says.

Today, HRCP plays several roles, including monitoring rights violations, seeking redress through public campaigns, lobbying, and intervention in courts. It organizes seminars, workshops, and fact-finding missions. It also publishes its flagship annual report, State of Human Rights, widely considered the most comprehensive document available in the country.

In the lead-up to this year’s elections, HRCP began issuing warnings over electoral fairness, pointing to pre-poll vote rigging and blatant electoral manipulation. “At this point, there is little evidence to show that the upcoming elections will be free, fair, or credible,” said HRCP co-chair Munizae Jahangir during a January press conference in Islamabad.

A lot of what HRCP observed on the ground had already occurred in 2018 when pre-election engineering and military intelligence saw Khan coming into power in the first place. “There were well-documented incidents of candidates being forced to leave their party to join Imran Khan's party,” Jilani says. “And when the military and Khan fell out and started exposing each other, it led to a lot of suspicion about the contiguity of the 2018 election results.”

Still, this year’s results have managed to surprise everyone, including Jilani. “It’s strange for me to say this, but I don't think the Pakistani public has ever played a strong role in enforcing democracy in this country,” she says. “Yes, there have been very brave, courageous people who have waged some kind of opposition or resistance, but we have not seen a public uprising against the military takeover of political space in this country.”

Read More: A Make-or-Break Year for Democracy Worldwide

It’s for this reason that PTI’s surprise win has also been so exceptional, Jilani says: “Despite the constraints imposed and attempts made by the military establishment to deter or discourage the voters from voting, there was still a huge number of people who did come out and vote.”

What PTI-affiliated independents do next also matters greatly. “They may choose to join a different party,” Jilani speculates. “On the other hand, the PTI has lost the status of a party, so they will have to find legal ways under the Constitution to declare themselves as a single party and form a government.”

And then there’s the matter of Khan, who will remain an important political figure even after the government is formed, given that so many candidates are contesting in his name. “His party, the PTI, still exists. Now, it will have to do a lot of things in the right way,” she says, referring to the slew of corruption allegations that PTI officials are currently facing in court.

Pakistan also needs to form a government that can grapple with its looming economic crisis. The country’s annual inflation hit 28% last month, while its debt burden has risen rapidly, relieved only marginally by a $3 billion bailout from the IMF. “Pakistan’s voters may not always have the political will or know-how, but they do care about the cost of living. Maybe these conditions will compel these people to move towards some kind of stability,” Jilani says.

Above all, she believes that good governance can only occur with a responsible opposition. “We need to see mutual respect between the government and the opposition. If elected officials act like goons in Parliament by going after each other's reputation with abuse and slurs, as we have seen in the past, then that is not going to happen,” she warns.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Astha Rajvanshi at astha.rajvanshi@time.com