Even now, when so much of the South has been strip-malled, skyscrapered and paved over, we think of the place differently, as a part of the country with a dogged mystique, a permanent residue of idiosyncrasies and a particular burden of history. “When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South,” an exhibition in New York City that continues through June 29 at the Studio Museum in Harlem, is about ways that African-American artists have tried to make use of the peculiar materials, both physical and psychological, that the Southern states have afforded them. Many of the 35 artists in the show, organized by Thomas J. Lax, actually live outside the region–Brooklyn seems to be a common fate–but all of them have a link of some kind to the place, whether by birth, upbringing or just as a source of inspiration. Quite a few fall into the unwieldy category of outsider artists: self-taught practitioners who may also be eccentrics, hermits, religious visionaries or diagnosed schizophrenics. Though the show also includes work by artists who are none of those things–some as famous, highly schooled and eminently sane as Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems and Theaster Gates–it keeps circling back to men and women who made their art, some of it pretty marvelous, in prisons or hospitals, or just while attuned to a mental frequency all their own.

This would describe the output of Frank Albert Jones, born in 1900, who began making his thorny colored-pencil drawings in 1964 while serving a life sentence for murder at the Texas state penitentiary in Huntsville. Almost his entire body of work consists of intricately rendered imaginary buildings–haunted houses of incarceration–where every room is bordered with bristling red and blue points, like barbed wire. Jones called these places devil houses, and in each of their rooms he put abstracted representations of the ghosts that he called haints. He claimed to have seen them all his life and said they lured people in to “do bad things.” If the devil houses are places where Jones sublimated his experience of prison–clocks figure in a lot of them–they work for us as strangely potent diagrams of a bristling inner life.

Those haints are a reminder that the South, or at least the old South, is at times something like America’s very own Ireland, a land of spirits, phantoms and folktale talking animals. They turn up in the photographs of the multimedia artist Ralph Lemon. Here’s a woman sitting on a sofa, a deer mask on her head; here are two men dressed as rabbits in the same paneled living room–beasts of the southern wild, turning up at home. For the remarkable Minnie Evans, who spent much of her long life as a groundskeeper and ticket taker at an arboretum in South Carolina, the part of nature that mattered was plant life, especially flowers, which she responded to with something like a religious ecstasy. (God and his angels were her other great preoccupations.) Blending floral imagery with human features, her densely worked-up paintings and drawings are filled with arabesques and medallions so tightly detailed, they remind you that a shared characteristic of a lot of outsider artists is to blur the line between fastidious draftsmanship and obsessive-compulsive behavior.

Among self-taught artists, probably the most famous these days is Thornton Dial, a man of sound mind and sizable gifts. A retired factory metalworker living in Bessemer, Ala., for decades, Dial has made sculptures and welded metal wall assemblages so richly imagined and executed, they make self-training seem a much better idea than the M.F.A. program at Yale. His metal works made from scrap-heap materials are a sophisticated descendant of the “yard show” displays he saw in the African-American neighborhoods he grew up in, yards full of DIY sculptures and ragged glories his neighbors made from discarded household items. Some of that same spirit, a tender regard for things put aside, invests Dial’s darkly radiant painting from 2013, Old Documents, in which bits of flotsam from his studio and relics of Bessemer are embedded in the paint like sedimentary layers of memory.

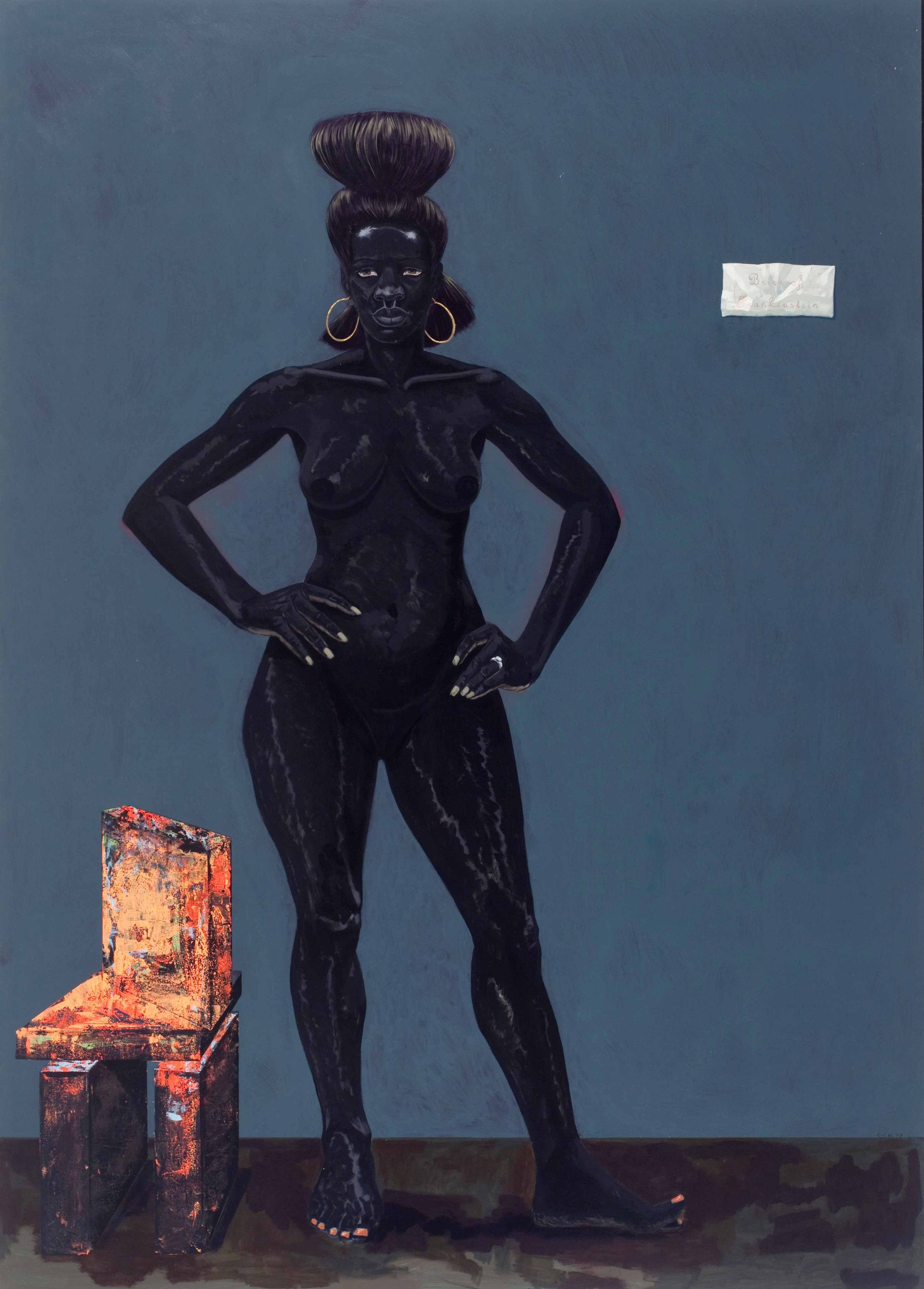

Even some of the academically trained artists in this show draw on folk-art traditions, though they take them down paths the folks may not have tried. Whatever else it is, the majestically strange wooden doll by the venerable L.A.-based artist John Outterbridge–Untitled, from the mid-1970s–is a hybrid of voodoo effigies and surrealist objects, like the perverse dolls that the German artist Hans Bellmer started making in the 1930s. In their different ways, shaman figures and Surrealist fetishes are both meant to tap into buried sources of power: magical, psychic or erotic. In that disturbing little mannequin, Outterbridge has his finger on all of them. Meanwhile, the well-established Chicago-based painter Kerry James Marshall borrows from the mood and imagery of 19th century Southern Romanticism–a literature full of horror and the grotesque, featuring slaves as the perennial Other–and links them to the most famous brand name in the Gothic novel. What that produces is Bride of Frankenstein, from 2009, a fierce emblem of fear and desire, a monumental woman who stirs up notions of black sexuality and the anxieties it has sometimes aroused in white culture. The sulfurous chair at her feet stands in for both.

Like we said, even these days, the South has mystique to spare.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com