I believe that there are five big, interrelated influences that are driving the changing world order and that they tend to evolve in big cycles. They are:

- how well the debt/money/economic system works,

- how well the internal order (system) works within countries to influence how well people within them work together,

- how well the world order (system) works to influence how well countries work with one another,

- the force of nature, and

- how well humankind invents new and better approaches and technologies.

How these five forces work and interact with each other shapes what happens. In this post, I will look at all five of them and their prospects for 2024. As always, the headline points are in bold so you can read this quickly by just scanning them instead of reading the whole thing.

2024 Will Be a Pivotal Year

As explained comprehensively in my book Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order, there are cause/effect relationships that tend to unfold in big cycles that, like people’s life cycles, can be measured to understand how healthy a country is, where it is in its life cycle, and what its prospects are. I use these measures to provide relatively good estimates of the next 10-year growth rates for 22 countries. I share these numbers periodically and am working on putting them out in the next month or so. This template gives my baseline projections. Then I watch how actual developments unfold relative to expectations.

What I will explore today is how actual developments are transpiring relative to the template explained in the book with a focus on 2024. As you will see, the world order is by and large changing according to the template.

Within each Big Cycle arc of history, there is a string of years that have events of varying significance in them. While most years fade into insignificance, a few (e.g., 1914, 1917, 1918, 1929, 1933, 1939, 1941, 1944, 1971, 1982, 1989, 1991, 2001, 2008, 2020) stand out. 2024 will likely be one of those years that stands out because all five major forces are approaching or are on the brink of seismic shifts. To clarify, I don’t mean that 2024 will necessarily be a year of seismic shifts that will end democracy in the US and/or take the world over the brink into a war (like 1914, 1929, 1939, 1941, etc.)—I think that there is only a 20% chance of that, which is still too high for comfort. But I do mean that 2024 will almost certainly be a pivotal year in a number of ways—for example, we will find out whether the existing democratic order in the US will or won’t hold up well, and whether or not the world’s international conflicts will be contained. Of course, like all years, 2024 and the events in it will be just small parts of the long string of years and events that make the Big Cycle arc of history, which is what is most important to pay attention to. What follows are my quick thoughts about the status of the five big forces as they will likely affect 2024.

As you might know but is worth repeating, my very conceptual, very macro model for how the world works is that:

- Productivity rises due to human inventiveness of new and better ways of doing things, especially of new technologies, and produces rising incomes (e.g., rising real GDP) and rising living standards over time, while…

- …short-term (approximately seven years, give or take about three years) and long-term (about 75 years, give or take about 50 years) debt-money-economic cycles produce corresponding changes in markets and economies, and over the long term produce wealth gap cycles that cause and are affected by…

- …short-term (approximately seven years, plus or minus three years) and long-term domestic peace-conflict political cycles of roughly the same lengths as the debt-money-economic cycles that are manifest in political order and disorder cycles and…

- …short- and long-term international peace-conflict cycles that are due to changes in the relative powers of countries that result from their relative performances in handling the previously mentioned influences and…

- …acts of nature, most importantly droughts, floods, and pandemics, that affect and are affected by the previously mentioned forces. Conceptually it looks like this:

Of course, that is a very conceptual, macro, and imprecise model that is fleshed out in much greater detail and with much greater precision in my operative decision-making systems.

Let’s now look at these five big forces and where they are in the Big Cycle.

Of course, a lot is happening in many countries that together makes up the whole global picture, and I won’t be able to cover each country in this brief memo. This description of what happened and where we are in these cycles will skew to what happened in the US because it’s most important and because what happened in most other countries was analogous (i.e., the economic weakness due to COVID, how central governments and central banks stimulated to handle it, inflation rates rising, monetary tightenings by central banks, etc.).

1. The Debt-Money-Markets-Economy Force

By my measures, the near-term (one year ahead) riskiness of this force is moderately low when looked at in isolation (i.e., when not considering the other four forces) and is moderately high when considering the effects of the other four forces. More specifically, a) the current market pricing is now roughly in line with the current fundamentals (maybe a bit expensive for US bonds and stocks) and b) I don’t see any really big debt/money/economic problems on the horizon (like in 2008) that can’t be well-managed. At the same time, the internal conflict force in conjunction with the 2024 elections, the external conflict force that will determine how international conflicts unfold, and the climate force that will certainly be costly (but how costly is as unpredictable as the weather) all add risks for markets and economies in 2024. It’s also true that the technology force will evolve a lot in 2024 and will certainly provide a big productivity boost and risks for the economy down the road that will produce great and risky investment opportunities.

Looking back over the last five years, we went through one big short-term debt-money-economic cycle that consisted of a big down in markets, economies, and prices that led to a big stimulation (i.e., money and credit expansion) by central governments and central banks. This led to a big swing up in markets, economies, and prices that led to a big tightening that is nearly over as market pricing, inflation, and real growth have been brought to near equilibrium levels.

More specifically, this cycle transpired as follows: the big down was caused by the acts of nature force via COVID, which prompted the big stimulation that was executed by central governments sending out a lot of money that produced big deficits and debt sales that were accompanied by central banks printing a lot of money and buying a lot of debt and keeping interest rates artificially low. That enormous amount of government spending—much more than was needed to compensate for the losses of economic activity—occurred for both economic reasons (to offset the economic free fall caused by lockdowns) and political reasons (the election of President Biden and the Democratic Party favored more distributions of money and more spending). This large, monetized fiscal stimulation shifted a lot of wealth to the private sector from the government sector. It is noteworthy that this type of big, coordinated fiscal and monetary policy to get money in the hands of the private sector has happened repeatedly in history during times of extreme distress. I call it Monetary Policy 3 and explained it in depth here. As a result of this stimulation, inflation and growth increased. Also, the international geopolitical influence via international conflicts and the increased emphasis on security rather than cost efficiency further added to inflation. That high inflation led to the rapid tightenings that brought real interest rates from extremely negative to moderately positive and tightened credit. What was surprising about the tightenings is that they didn’t hurt economies as much as was expected. Expectations were based on what happened before and this case was different primarily because the private sector’s incomes and balance sheets were in good shape.

So, in 2023 conditions transpired better than what was priced into the markets (i.e., economies stayed stronger and inflation fell faster than the consensus expected), which led to better-than-expected returns for equities, especially for AI-related companies like the seven companies called the “Magnificent Seven,” with attractive returns for cash, nil returns for bonds, and mixed returns for commodities. As for growth, with unemployment relatively low while wage inflation was relatively high, personal earnings were good, which helped the economy withstand the tightening. At the same time, the effects of higher interest rates on interest-rate-sensitive sectors such as real estate, venture capital, and private equity were relatively depressing and included some debt bubbles bursting quietly.

Looking back on 2023 with a bottom-up micro perspective, the big, well-financed, new-era disruptor companies (especially AI-related companies) did very well relative to old-era companies that are being disrupted. Earnings expectations for them jumped, as reflected in interest-rate-adjusted PEs jumping. As a result of the MP3 fiscal-monetary policies, private sector balance sheets and cash holdings improved. Additionally, with regard to 2023 inflation, there were better-than-expected adaptations to supply chain disruptions and government-created policies to favor onshoring and nationalism over globalization and low inflation in the goods-producing sectors because of productivity improvements. Also, the previous spikes in commodity prices were followed by downward corrections, which produced commodity deflations that helped to lower the overall inflation rate numbers. Goods inflation was also relatively low and higher interest rates caused price weakness in interest-rate-sensitive items, so real incomes rose despite the tightening.

This short-term debt cycle has thus far lasted nearly five years, is the 13th since the new world order Big Cycle began in 1945, and is unusual because of what caused it (a pandemic) and because of the amounts of coordinated MP3 policies employed by central governments and central banks, which were the largest since World War II. It also followed the classic cyclical steps in that the weakness led to the stimulation, which led to the pickup in growth and inflation, which then led to the tightening, which weakened inflation and growth.

Meanwhile, the long-term debt cycle continues to progress toward greater levels of indebtedness (especially government debts), which will eventually be unsustainable and crisis-causing if not rectified. The deteriorations in government finances didn’t have much of a harmful effect because the incremental debt service expenses were heavily absorbed by central governments and central banks, because the faith in the government’s finances was maintained and because the Treasury managed its debt offerings well (e.g., by shortening the maturities of debt sold) to help fit the demand. For reasons I will explain more comprehensively at another time, I expect that if these policies continue to be used as they have been used and as they are projected to be used (i.e., excessive government spending and debt creation accommodated by central bank policies that keep real interest rates low and money and credit plentiful), it will in the long run create big financial problems, but that’s a topic for another time.

The way markets work is that their prices paint a picture of the future that is constantly changing, so changes in the picture of the future lead to changes in prices. For example, one can calculate the expected amount of inflation by comparing inflation-indexed bonds and nominal bonds, and one can bet on it being higher or lower by taking positions in these bonds, knowing that if your estimate is better than others you will make money. The picture that market prices are now painting is for inflation to fall to central banks’ targets, for real growth to be moderate, and for central banks to lower interest rates fairly quickly—so the markets are now reflecting a Goldilocks economy.

As for the economy in 2024, it appears likely that inflation won’t fall as much, growth won’t be as much, and interest rates won’t be cut as much as is reflected in the prices. More specifically, growth will slow, as the cash/savings pile that was built up from the big 2020 and 2021 stimulations is being run down and the interest costs on existing debt will rise as debts mature, which will require debtors to refinance their debts at higher interest rates. As for inflation, if there are no shocks from exogenous forces, I estimate that inflation will probably be about a percent higher than expected. Given that there is a lot of imprecision in my estimates relative to what will actually happen, I don’t have strong bets placed on them.

At the same time, 1) internal political conflict forces, 2) external geopolitical conflict forces, and 3) acts of nature provide added downside risks to markets and economies, while 4) the technology force provides very interesting disruptive opportunities. These four forces will affect trade and regulatory policies, economic and military alliances, and the costs of paying for and the disruptions caused by economic and military wars, climate, and a lot more that will affect markets and economies.

It appears to me that the biggest risks in 2024 appear to come from the risks of big internal and/or external conflicts. As always, these conflicts will be over money and power, and who wins them will be determined by the amounts of money, power, and smarts the competing sides have to fight these conflicts. Let’s start with the internal conflict force.

2. The Internal Conflict Force

I see this as the biggest single risk for 2024.

A number of countries, most importantly the U.S., are experiencing classic big internal conflicts over wealth, values, and power. The ways these conflicts are happening make it clear that they are in the classic Stage 5 part of the Big Cycle, which is the stage just before civil war (it is explained in detail starting on page 167 in my book). This is when people align on one side or the other and fight intensely for their side or hide from the fight, and few people engage in thoughtful disagreement for the common good. In these times of irreconcilable differences, there is little respect for the existing order of rules and judges, so whether someone is guilty or innocent is judged and sentenced by intensely opinionated people (e.g., ”cancel culture”) rather than an evidence-based justice system. It’s a time when democratic orders are at risk of being disrupted because democracies require people to engage in thoughtful disagreements and follow a system that resolves differences by following rules.

We are seeing this classic Stage 5 dynamic all the time, most recently in the following events:

- The testimony of the university presidents in which they didn’t take a side or speak forcefully in favor of anything because they were worried about being attacked by one side or another (which they ultimately were).

- Some states trying to prohibit Donald Trump from being on the ballot, which will lead to a Supreme Court decision that will probably lead to whichever side doesn’t get its way arguing that the Supreme Court is politically corrupt and another weakening of support for the Supreme Court.

- The brutalities suffered by Israelis and Palestinians leading to such strong reactions from people fighting for one side or the other that they attack people who express sympathy for the people of the other side is another example. One would think that we all should be able to agree that the horrific losses of both sides are terrible, yet most people pick a side and fight for it, or hide from the fight, and few people engage in thoughtful disagreement in support of a common good.

We are also seeing many other classic signs of Stage 5 behaviors such as politicians using their powers to weaken their opponents or even to threaten to jail them; unwavering voting along party lines even when the parties want extreme actions; pervasive lying, distorting, and taking political sides in the media; people moving to places to defend themselves against others who are different whom they feel threatened by; etc. This highly polarized, antagonistic mindset will be carried into the 2024 U.S. elections so it is difficult to imagine that either side will accept losing and subjugate themselves to the policies and values of the other side. Those policies and values are too abhorrent to those on the other side and respect for the rules is too low for those on both sides. I am not saying that we won’t adhere to rules and get through this with our domestic order system intact, but I am saying that it’s difficult to imagine how that will happen.

Unfortunately, this internal conflict evolution is transpiring almost exactly as laid out in the template explained in my book. When I published excerpts from the book online in 2020, including the prospect of some form of U.S. civil war, it was considered kooky. Then came the events of January 6, 2021.

When I wrote the book, lessons and indicators that I learned from history led me to estimate that the probability of some form of civil war in the U.S. was around 30%. That was considered an unrealistically high estimate. Now it is not. In fact, ~40% of Americans surveyed by YouGov think that it is at least somewhat likely that there will be a civil war in the next decade. I now estimate that the risk of some form of civil war over the next 10 years is about 50%, with 2024 being a high-risk year.

Regardless of what happens in the U.S. elections, the outcomes will have big implications for what will happen in the markets, economies, the domestic order, the world order, geopolitical and economic issues, the handling of the climate, and technology issues because each of the sides has very different views about these issues. The amounts of economic regulation, taxes, immigration, trade agreements, and tariffs as well as social issues will be handled very differently, depending on who is elected. For example, if Donald Trump is elected there is a good chance he would leave NATO, put 10% tariffs on all imports, reduce income and corporate taxes, greatly reduce regulations, reduce green initiatives, pursue much stronger policies of the right, and become more isolationist and nationalistic. If President Biden (or the Democrat who will replace him if the strains of the job impact him) wins, he will pursue diametrically opposed policies. The ideological fight of the extremists is real. If things continue going as they are, voters might eventually be faced with the question, “If forced to choose, would you prefer a fascist or a communist?” In any case, there is no doubt that 2024 will be an important, pivotal year for determining how the domestic order and all that it influences will go.

3. The External Conflict Force

I see this as being a moderately high-risk area in 2024 as the Big Cycle continues to evolve consistent with the template, though there have been some improvements in U.S.-China relations.

For reasons explained in my book, there has always been a big cycle from one world war to another in which relative powers and relative authority in setting how the world order works evolve. The dominant power has a dominant say in determining how the world order works until the two leading powers have irreconcilable differences and fight. This typically takes the form of a war that makes clear which country is the dominant power and what the world order will be like. Graham Allison, in his excellent book Destined for War, dealt with the rising power challenging the existing established power part of the cycle very well. Both of us, and many others, agree that a great power conflict between the U.S. and China is now going on. Whether that leads to intense competition or outright war is not yet known. I am staying on top of this closely and must say that the odds keep changing because these two countries are so close to the brink.

The risks of a terrible economic or military war between the U.S. and China rose to a peak last March and have declined significantly over the last 10 months. Last March, I made two visits to China when both the Chinese and American sides were very antagonistic and not talking with each other, and I came away with the belief that there was a dangerously high risk of some sort of very destructive economic or even military war because there were a number of red lines that were close to being crossed and elections in Taiwan and the U.S. in 2024 were likely to intensify the conflict. This is what I wrote then. That very scary possibility of going over the brink led to a desire on both sides to take a big step back, which led to a good meeting between President Biden and President Xi at the APEC conference in San Francisco and follow-up meetings and communications and productive cooperation in a few areas.

Still, there is a great power competition that is happening economically and geopolitically all over the world. The battles are for market shares and natural resources and are intensifying as China becomes more competitive (e.g., in solar and wind power generation, electric vehicles, batteries, high-value-added manufacturing, etc.). The resulting change in the world economic order is leading to many traditional producers and markets such as the European ones fading in importance and emerging ones such as India, the ASEAN countries, and the GCC countries rising in importance. Though an oversimplification, as a sweeping generalization, the trend is toward: China and the United States being the leaders in new, exciting, cutting-edge industries and other economies being suppliers of ingredients such as minerals (e.g., Africa and South America), markets for their products (e.g., Europe for Chinese solar and wind energy generation and electric vehicles), emerging markets and producers (like the ASEAN countries), or lesser rising or declining economic powers.

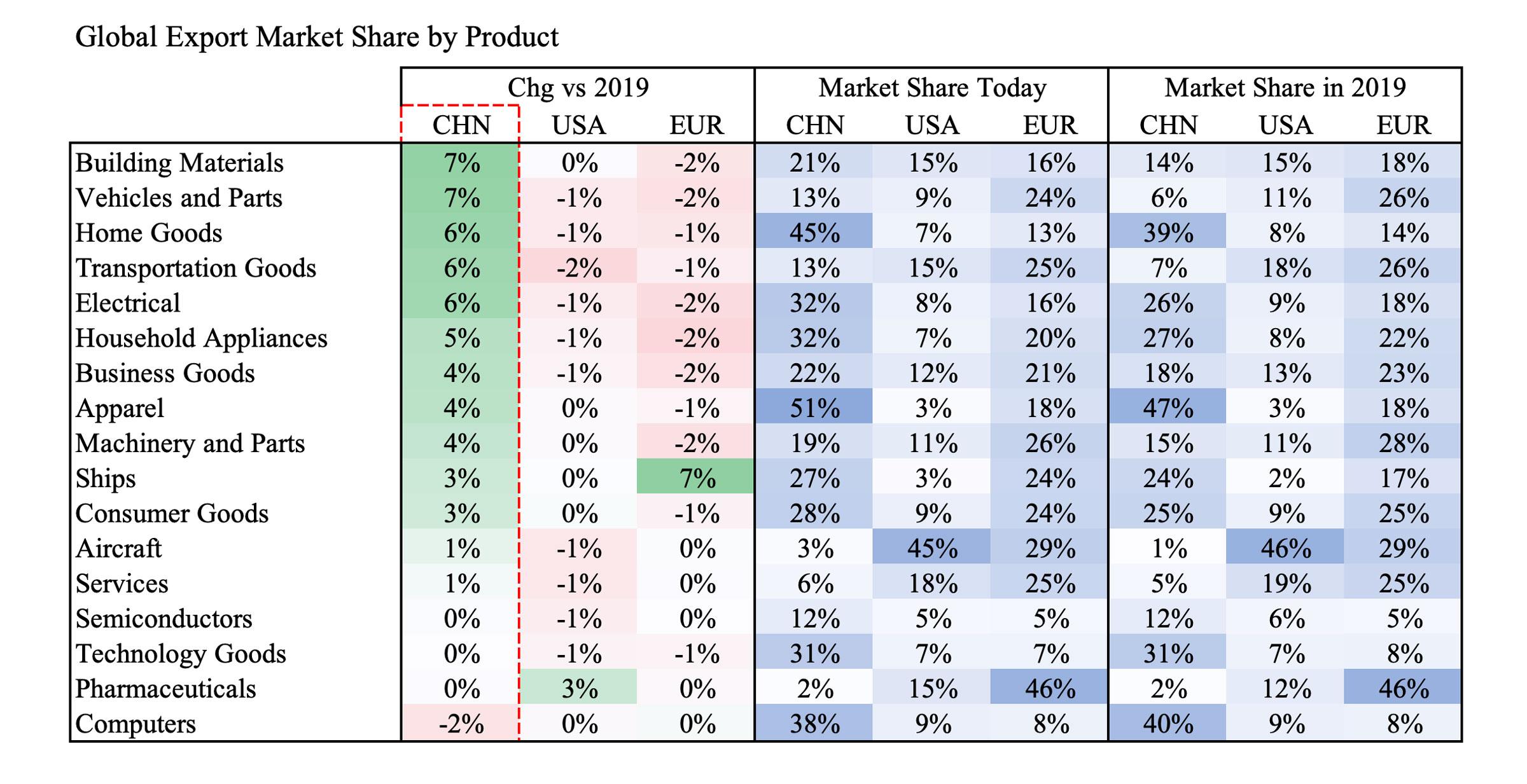

You can see China’s emergence as a global competitor by looking at global exports. The table below shows the global export share by product area between the U.S., Europe, and China since 2019. As you can see, in many major product areas China is now a global competitor (and in many cases the global leader)—most notably in industries like automobiles, industrial machinery, and ships. At this point there are only a few areas where China is not yet a major competitor with the U.S. and Europe (aircraft, pharmaceuticals, and services).

Since economic, geopolitical, and military powers go together, this intense competition isn’t limited to economics. Though for the time being China doesn’t want to appear to be an overt geopolitical and military competitor, it is certainly becoming a strong one. For example, it is taking a leading role among emerging economies while it is actively involved with them economically. For these reasons, the global economic, geopolitical, and military competitions between the U.S. and China will likely be intense, though probably not violent, in 2024. My read is that they will have conflicts that they talk about and try very hard to work themselves through. While appearing dramatic, these conflicts won’t lead to a terrible conflict. So, while there will be two notable challenges ahead in the form of U.S. and Chinese reactions to last weekend’s Taiwan election and the upcoming U.S. elections this fall, I think that they will probably be handled in a way that won’t produce serious damaging wars, though they might produce some dramatic public displays of power.

Of course, the U.S.-China conflict isn’t the only one going on, and since these conflicts are all related, this is getting complicated and risky in many ways that I won’t delve into and admit I don’t fully understand. While we are all aware of the possibility of the Russia-Ukraine war and/or the Israel-Hamas war spreading, I think that there is about a 70% chance that they won’t because all of the large and mid-level power countries, including Israel, Iran, and the GCC countries—like the Americans and the Chinese—don’t want to cross the brink into mutually assured destruction.

For all these reasons, I view the risks of this force as moderately high.

4. The Force of Nature, Most Importantly Climate Change

While I’m no expert on climate change, there’s no getting around the reality that as a global macro investor I need to understand enough about it to understand its impacts, so I have studied it. I recently covered what I learned in this study—which, in a nutshell, is that not nearly enough money will be directed to limit global warming to about 1.5°C because it is unprofitable for those who have the money to contribute to or invest in the effort to try to prevent global warming, so there will likely be big impacts from it and big adaptations that will have to be made. In brief, it appears climate change will lead to both bad changes (e.g., droughts and floods, intolerable temperatures that will lead to great migrations of people, rising ocean temperatures and rising sea levels that will inflict great damage, etc.) and good changes (e.g., improved weather and harvests in northern areas such as Canada, the opening up of the Northern Sea Route, etc.), though much more bad, costly things than good things. These changes will lead to more economically motivated investments and spending. That is because those with money will spend more money on adaptations that they need and/or they will invest to take advantage of the increased opportunities to make money from providing these adaptations. So, I expect much more money to go into adapting to climate change than went into preventing it. For example, I expect that there will be great growth in climate-change-related investment funds that are chasing the financial opportunities that will come from climate change adaptations. As for the impact of climate change itself in 2024, I can offer you little more than a trendline extrapolation of what is happening with severe weather events, bumped up for the fact that 2024 will be an El Niño year, which means that it should be considered a risky year.

5. The Force of Humankind’s Inventiveness, Especially of New Technologies

This is the force behind productivity increases that produce rising living standards that are reflected in measures like real GDP and life expectancy.

Productivity increases = inventive, talented people who work well together + financial resources + technologies that further enable them (also known as entrepreneurship).

This is the greatest force of humanity and it has never been better. It is fostered by 1) good education, 2) capital markets, including venture capital, private markets, and public markets, and 3) thinking aids like artificial intelligence that are supplementing and turbocharging human intelligence. Turbocharging human intelligence will have big impacts on everything. As mentioned earlier, the effects of artificial intelligence are being reflected in market pricing via improved prospects for profits of those that produce it, and it is certainly the case that 2024 will be a pivotal year for this influence, as there will be much more learning and development during 2024, which will have big productivity-boosting impacts for many years to come. Of course, like all powerful new technologies, this one brings risks of possible harms such as advancing ways people can hurt each other in wars and having technologies replace some people in jobs while boosting the wealth of others.

More than anything, how good or bad 2024 will be will depend on how good or bad people are with each other. History shows that all these things can be worked out to produce peace and prosperity if there is smart bipartisanship.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com