Between 1936 and 2012, 11 out of 14 presidents seeking a second White House term were re-elected. This success rate convinced many that, as with other elected offices, incumbency offers distinct advantages for the presidency.

But what if this conventional wisdom is now wrong? What if, in an era of profound distrust and ingrained political disaffection, incumbency has turned into disadvantage? And if so, can an incumbent somehow channel the discontent and still win?

There are no snappy answers here, because the political moment we inhabit now is truly uncharted. The distinct combination of hyper-partisan polarization, widespread mistrust, and two extremely unpopular presidential frontrunners atop two very unpopular mainstream parties is unprecedented, and extremely dangerous.

But to face it squarely and think productively about the future, we have to stop pretending the old theories of presidential elections still apply.

The long-standing reasons political scientists gave for a presidential incumbency advantage included: 1) political inertia and status quo bias (most people will support an incumbent they voted for the last time); 2) experience campaigning; 3) the power to influence events (such as well-timed economic stimulus); 4) the stature of being a proven leader; 5) the ability to command media attention in a “constant campaign” environment; and 6) a united party with no bruising primary challenges.

Today, these advantages seem less clear. Instead, growing disadvantages have supplanted them: Unrelenting media scrutiny; a bruising political environment; pervasive anti-politician bias; and above all, a spiraling hyper-partisan doom loop of animosity and demonization that imposes a harsh starting ceiling on any president’s approval.

For much of the 20th century, presidents could benefit from incumbency because voters were more likely to judge presidents on their individual character, not only their partisan affiliation. Winning a presidential election relied on keeping some of that cross-partisan support, which was there for the taking.

Presidential approval ratings went up and down based on real-world events. A foreign attack could unite the country behind a president, as it did on 9/11. A booming economy (even one juiced by short-term stimulus right before an election) could boost presidential approval.

Beneath this variable support were media and partisan elites on both sides who sometimes withheld criticism, and at other times unleashed it. Both Bush 41 and Bush 43 earned sky-high approval at moments of foreign conflict because elite Democrats publicly rallied behind them. Both lost that support when partisans on both sides re-calculated. But this reservoir of potential cross-partisan support gave presidents some room to maneuver, even to influence events, and appeal to cross-pressured moderates.

Today, the crucial swing voters are not the cross-pressured moderates of yore. They are the perpetually dissatisfied, and frequently disengaged. They all over the place ideologically, and most of all, frustrated with “the system.” They mostly come from the 28 percent of voters who now dislike both parties (up from six percent in 1994). Many still see differences between the parties. But It’s harder and harder to motivate voters on negative partisanship alone.

Yet, in an era of anger, campaigns continue to rely on demonization. It’s a dangerous tool with spillover consequences. No wonder almost two-thirds of Americans (65 percent) now report feeling “exhausted” when they think about politics, more than half report feeling “Angry,” and only one in ten say they feel “hopeful.” No wonder, it’s been 20 years since a majority of Americans said they were at least somewhat satisfied “With the Way Things Are Going in the U.S.” And for most of the past two decades, that share has been between 20 and 30 percent. (In October, it was 19 percent). Politics is all apocalypse, all the time.

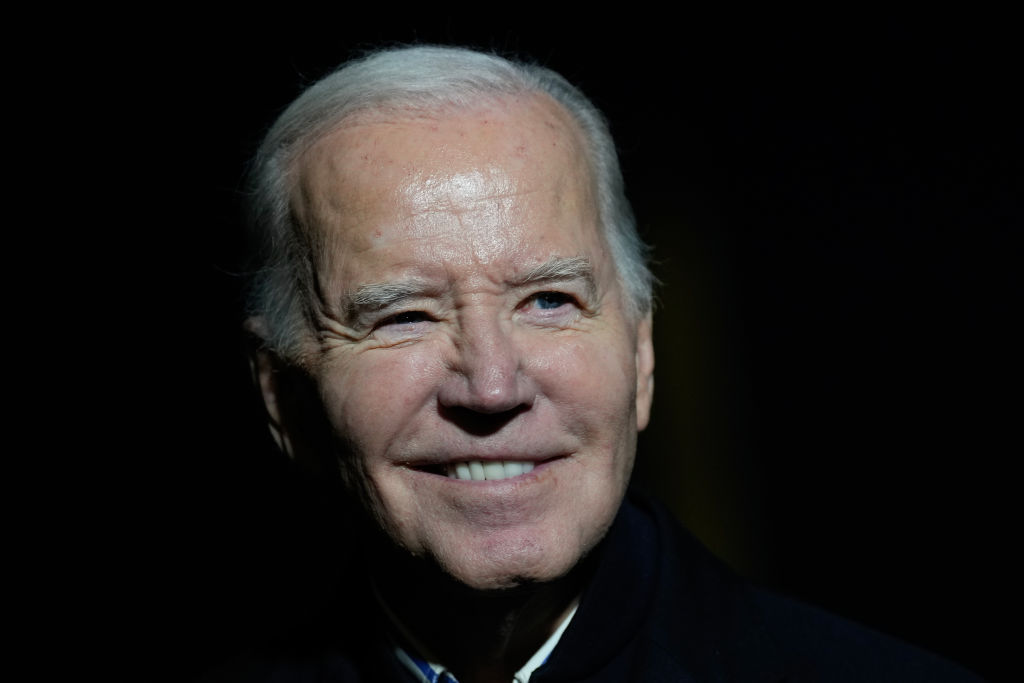

In 2020, dissatisfied change voters contributed to the anti-MAGA majority. They wanted Trump out of office. So, they showed up for Biden. Now, who knows? In 2020, Biden could promise an end to the craziness of Trump, and a presidency of unity, healing, and normalcy. In 2024, he'll be just another unpopular incumbent, in a political environment still screaming for something different.

The problem goes beyond the upcoming election. When perpetually dissatisfied voters hold the balance of power amidst hyper-partisan polarization, elections can become democracy roulette if there are not two dominant parties equally committed to the principles of liberal democracy (and right now, in America, there are not). Recent democratic breakdowns in Venezuela and Hungary, for example, follow this basic pattern: Voters only wanted change. They got authoritarianism instead.

If Democrats want to win in November 2024, they will need to tap into the sour emotions out there, instead of just pretending all is grand. Younger and working-class voters are especially feeling forgotten. Democrats really, really need these voters. So maybe less Mission Accomplished, and more I Hear Your Frustration. And yes, maybe a fresh face, who can at least offer novelty and change, and who hasn’t (yet) been beaten down by right-wing propaganda.

Regrettably, the sole proven tactic is to run against Donald Trump as a supervillain hell-bent on destroying democracy. It’s worked three elections running now (2018, 2020, 2022). Will it work again? The danger is when you’ve heard the same fire alarm enough times, some people tune it out. But the threat is still real, and getting worse. Trump’s ambitions for a second administration are absolutely terrifying. But equally terrifying is that so many voters either don’t believe it, are simply are tired of hearing it, or have somehow convinced themselves that Joe Biden is the even bigger risk.

Overnight solutions to this collapse don't exist. But longer term, American democracy needs new ways to re-connect the dis-connected and dis-engaged. This means giving voters more meaningful connections to national politics.

Practically, this requires better political parties. Not the two hollow, donor-driven parties that have alienated so many Americans and driven the two-party doom loop of hyper-partisan polarization. We need new parties. We need more parties.

To make this all possible, we need not just organizing, but powerful institutional changes that create new opportunities for parties to form. My preferred reforms are fusion voting and proportional representation.

But for the next 11 months, we need to understand one big thing. The old rules of presidential elections don’t apply anymore. Americans are deeply frustrated. Few believe things are going well. The parties and candidates who can channel this better will win this time. Perhaps Democrats can do this. But unless they can turn that discontent into meaningful post-elections changes that help more Americans feel heard and connected, the dissatisfaction will only get worse. The radical responses will grow more extreme, and the next election may go the other way. Except, if this continues much longer, one day, there might not be another election.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com