On Sept. 11, 2001, the U.S. prepared for a dramatic and sudden military response to the worst attack on American soil in the country’s history.

But there was a problem. Normal military communications between the U.S. and Russia had been severed after a hijacked plane crashed into the Pentagon. As the U.S. sought to move its military forces to the highest state of peacetime readiness, there were concerns that this might raise alarm bells in Russia.

One line to Moscow was left standing.

“At this time the United States has moved to DEFCON THREE (3). This is not directed at Russia, this is due to current emergency situations,” the message read, sent to the Russian Ministry of Defense, on the banks of the Moskva River.

Since 1988, the State Department’s Nuclear Risk Reduction Center (renamed the National and Nuclear Risk Reduction Center in 2021) has maintained a direct line to the Russian Armed Forces.

In the corner of their office today, in a windowless room on the fifth floor of the State Department in Washington D.C., hangs a framed printout of the message sent to Moscow. It's the clearest distillation of the NNRRC’s task to date, State Department officials say: to avoid the chance of misunderstandings leading to an accidental conflict between the two superpowers.

Established after a string of near-misses that nearly led to an all-out nuclear conflict during the Cold War, the NNRRC became the central nervous system for the U.S.’s arms control efforts, receiving thousands of notifications every year about weapons movements, warhead numbers, and military exercises from Russia and other partners. Today, the center takes in messages from over 50 countries in service of a range of treaties covering nuclear, conventional weapons, chemical, and cyber issues.

Read More: The Collapse of Global Arms Control

Even so, there is little doubt that the connection to Moscow is the center’s most important line. The NNRRC has two back-up facilities and its lines to Russia go along both satellite and undersea cables to ensure that the system stays up and running no matter what.

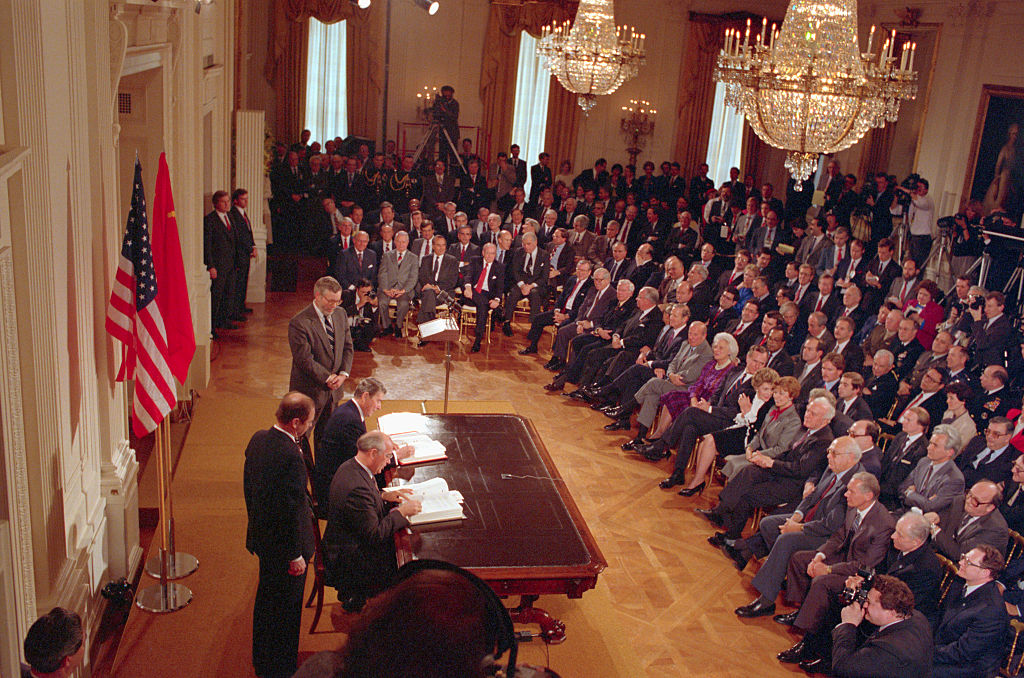

At any given time, a handful of case officers staff the center, sending regular messages to their Russian counterparts. On a series of large monitors, messages arrive in a mix of Russian and uneven English every two hours. The walls of the center are lined with rosy-tinted pictures from the tail end of the Cold War, depicting the signings of the founding of the NNRRC and other arms control agreements. During this golden age of arms control, the U.S. and the USSR were able to cooperate on a key set of treaties that contributed to an 85% reduction in the nuclear stockpiles controlled by the Kremlin and the White House. Today, that era feels increasingly distant.

One of the Only Remaining Lines to Russia

Few parts of the U.S. government are in as regular contact with Moscow as the NNRRC, and communications between the U.S. and Russia have slowed down dramatically since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia has opted out of a number of landmark arms control agreements, and as the U.S. and Russia stop sharing information about their military forces, arms control experts fear that the risk of nuclear miscalculation is once again on the rise.

Up until March of this year, the NNRRC received more than 1,000 messages annually from Russia, overwhelmingly under the New START Treaty. But after Russia suspended New START and a number of other arms control agreements, the day-to-day updates about Russia’s nuclear forces have stopped coming in. All that is left is the occasional notification about ballistic missile launches, a last holdover from an era where Russia and the U.S. cooperated on arms control.

So far, it appears that Moscow is content to keep on staffing its NRRC. A State Department official says that the day-to-day communications have continued unabated. “It seems that they share our view that there is a great value in maintaining this line,” says the official.

“The fact that the Russian government is committed to keeping the NRRC platform going is really one of the small positive signs that we have to keep holding on to at this point,” says Rose Gottemoeller, former Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security and co-author of a recent report on the NNRRC.

But the total notifications coming from Russia following the suspension of New START will likely amount to less than 10% of what they were in 2019, before COVID caused a temporary reduction in communication, officials say.

“A massive reduction in notifications,” says William Alberque, an arms control expert at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, “means a massive reduction in the sharing of information that the two sides use to prevent accidental conflict or ruinous arms races and an increase in the risk of potential conflict.”

Read More: Here’s How Bad a Nuclear War Would Actually Be

Over time, nuclear experts fear, each side's picture of the other’s nuclear arsenal will grow ever more opaque, increasing the chance of misunderstanding. “That lack of certainty may actually encourage things like an arms race,” says Alberque.

While “we don't depend on notifications alone to understand the status of the Russian strategic nuclear force,” Gottemoeller says, “we have lost something there. There's no question about it.”

Moscow Remains Silent

While the NNRRC continues its task of reducing the risk of accidental nuclear escalation, it was not designed as an arena for nuclear negotiations or to prevent purposeful escalation. For this, more traditional diplomatic efforts are needed.

For months, the administration has been pushing to bring an uncooperative Russia back to the table for arms control talks. In June, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said the U.S. is seeking dialogue with both Russia and China on nuclear arms “without preconditions.” Jill Hruby invited international observers to the nuclear test site in Nevada, to prove that the U.S. is not breaking the three-decade long ban on nuclear testing. And Washington D.C. has sent a set of informal arms control proposals to Moscow, Russian officials have confirmed.

So far, however, there’s been nothing but crickets from Moscow. The Russian embassy in Washington, D.C. did not respond to a request for comment. “They may not engage with us, and that’s a challenge,” says a senior State Department official, requesting anonymity to speak candidly. And when asked about the U.S. proposal by Izvestia, a Russian newspaper, Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said, “the situation is not conducive to the exchange of notifications, even on such key issues.”

Few arms control experts expect a quick reopening of talks between the U.S. and Russia. “Unless this situation in Ukraine comes to some kind of solution which both U.S. and Russia can live with,” Russia and the U.S. seem unlikely to return to the table for serious talks, says Andrey Baklitsiy, an arms control expert at the UN Institute for Disarmament Research.

Read More: She's Spent a Decade Fighting to Ban Nuclear Weapons. The Stakes Are Only Getting Higher

But in the absence of an arms control breakthrough, the NNRRC will continue its work maintaining and preserving the emergency line between the U.S. and Russia. Many experts say that establishing a similar risk reduction line with Beijing and other nuclear states could be a realistic move towards reducing the world’s growing nuclear risks.

At the NNRRC, they are taking steps to prepare for such an eventuality. The center is experimenting with machine translation in the case they eventually reach the limit of how many languages they can staff the center with 24/7.

In the meantime, watch officers will remain quietly at their computers, monitoring the lines.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com