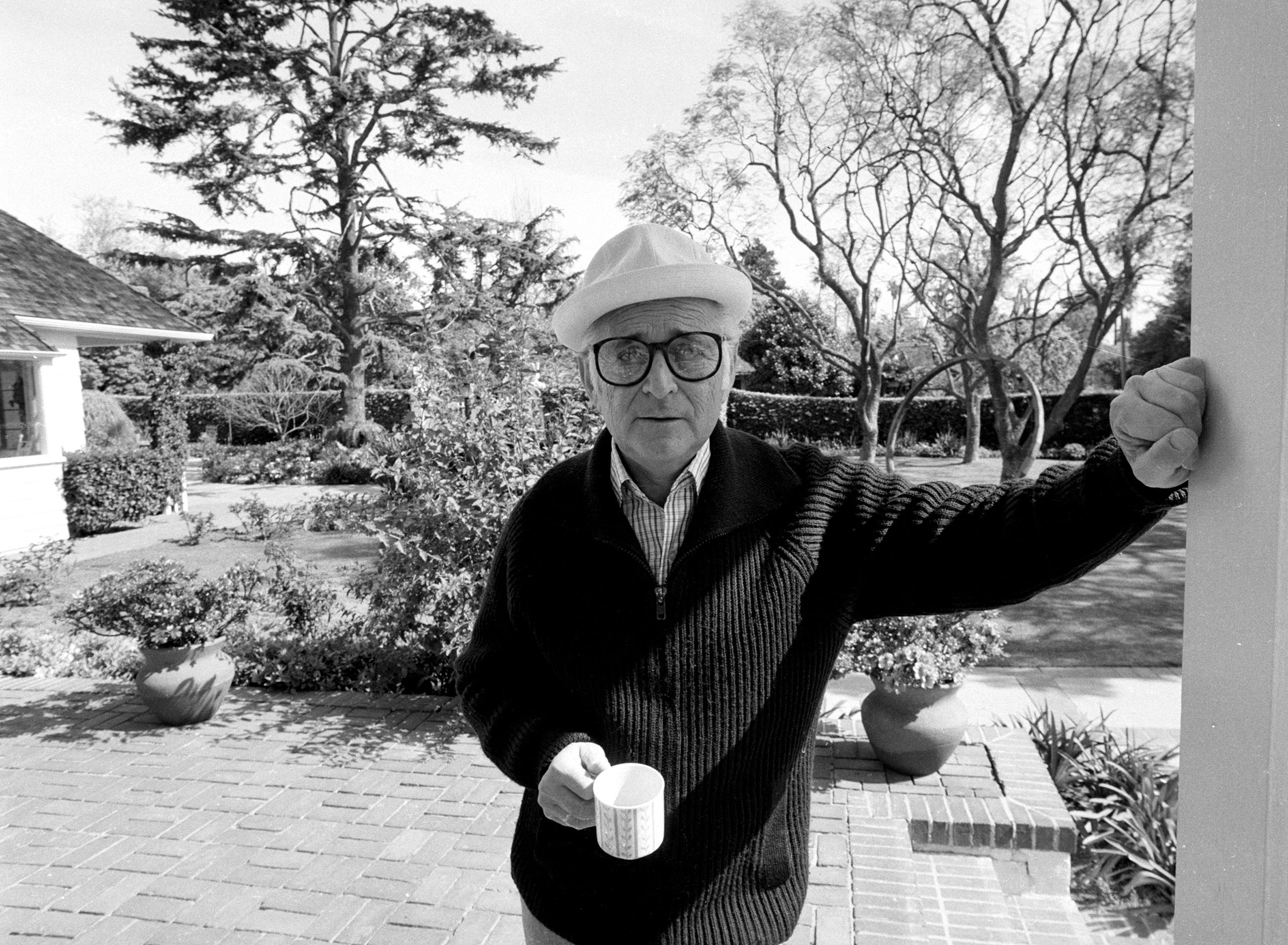

Norman Lear believed in dialogue. If Americans were one great, big, diverse, dysfunctional family, then the man who created some of the most important TV shows of all time knew that we’d have to keep the lines of communication open—even if that meant screaming at each other—to stay united. It was the principle that animated his work, throughout a seven-decade Hollywood career of unparalleled influence and a lifetime of advocacy for such progressive causes as civil rights, conservation, feminism, free speech and separation of church and state.

Lear died from natural causes at his Los Angeles home on Tuesday, Dec. 5, his family confirmed via a statement shared on the TV icon's website. He was 101.

The instinct to talk through our differences and, by doing so, honor our common humanity is what made Lear among the greatest comedy writers of his generation. Without skimping on laughs, his politically engaged sitcoms—All in the Family, Maude, Good Times, The Jeffersons and more—made their simple living-room sets the sites of weekly group-therapy sessions for a cumulative peak weekly viewership of 120 million. And his considerable contributions continue to influence a diverse group of television writers and showrunners working today.

When it premiered on CBS in 1971, All in the Family resembled no other family sitcom on television. As the archetypal conservative, white, working-class patriarch, Archie Bunker (Carroll O’Connor) ruled over his shabby Queens home like a tyrant—constantly bellowing orders at his daffy wife, Edith (Jean Stapleton) and picking fights with his daughter Gloria’s (Sally Struthers) hippie husband, Mike (Rob Reiner). Archie and the son-in-law he called “Meathead” clashed over the antiwar movement, electoral politics and the older man’s bigotry. And the Bunkers were forced to confront the accelerating pace of social change, as sexual mores loosened and their neighborhood integrated. “People still say to me, ‘We watched Archie as a family, and I’ll never forget the discussions we had after the show,’” Lear recounted in his 2014 memoir, Even This I Get to Experience. “And so that was the ripple [effect] of All in the Family. Families talked.”

Despite Lear’s own liberal sympathies, his characters were never one-dimensional mouthpieces for a particular party platform or point of view. Gloria’s feminist consciousness revealed Mike’s unexamined male-chauvinist tendencies—and suggested that he had more in common with his father-in-law than he would’ve liked to admit. Family’s fifth season helped to humanize Archie, opening with a timely, four-episode look at how the Bunkers weather the inflation crisis. And although the boilerplate media description of Archie at the time, as a “lovable bigot,” was a bit glib, it got at the rarely articulated reality that plenty of people with abhorrent prejudices or belligerent personalities still genuinely care for and are cherished by those closest to them. The implication was that the potential for love, empathy and relationships to overcome ignorance, even if they failed far more often than they succeeded, made tough conversations worthwhile.

This unique combination of gritty social realism and optimism about the power of honest dialogue to create positive change spilled over into Lear and co-creator Bud Yorkin’s subsequent projects, as a flourishing Family led to an expansion of the Bunkers’ universe. Maude spotlighted Edith’s cousin, played by the great Bea Arthur, a staunch Democrat, women’s libber and a formidable nemesis for Archie. Her decision to have an abortion, in an episode that predated Roe v. Wade by just a few months, remains one of the most influential moments in TV history. In a 2014 Fresh Air interview, Lear explained that he identified deeply with Maude because she was “an out-and-out liberal, as I am. No apologies in any direction. And the kind of liberal I am in the sense that I am not well-schooled in the political reasons for my being a liberal”; both arrived at their beliefs intuitively, guided by their own moral compasses.

It was probably no coincidence that Lear made his biggest impact in the 1970s, as a nation that had already been reeling from an epochal youthquake watched the Summer of Love descend into a dark winter of the soul. New movements for women’s and queer liberation, the rise of the religious right, the increasingly lethal and demoralizing war in Vietnam, Nixon and Watergate, a pileup of economic woes—all of it was weighing on and dividing Americans during Lear’s TV heyday.

He was also fiercely committed to depicting experiences that bore little superficial resemblance to his own. When Family premiered, representations of Black characters on TV had yet to meaningfully evolve past the racist caricatures of Amos ‘n’ Andy. Floored by Redd Foxx’s raunchy standup, Lear and Yorkin cast him as a cranky, scheming junk dealer with a long-suffering adult son (Demond Wilson). In 1974, their production company, Tandem, unveiled the pioneering African American family sitcom Good Times, built around Esther Rolle’s Florida Evans, a breakout character from Maude. They suffused it with the same combination of warmth, intergenerational tension and political urgency that fueled their other shows.

Lear wasn’t perfect; he sometimes failed to capture the Black experience in all its diversity. But, after Good Times cast members confronted him about racial stereotypes on the show and a delegation of Black Panthers complained that there were no prosperous Black families on TV, he responded with another long-running Family spin-off, The Jeffersons. The sitcom followed the Bunkers’ next-door neighbors George—an excitable foil for Archie—and Louise “Weezy” Jefferson (Sherman Hemsley and Isabel Sanford, in legendary performances) as the expansion of their dry-cleaning empire allowed the couple to “move on up” from working-class Queens to the posh Upper East Side of Manhattan. As Naima Cochrane observed in Vibe: “The Jeffersons addressed not just race and class, but also race vs. class. George wasn’t educated, but he worked hard, and expected his success to afford him respect and access—his theory was that green was more influential than black, and he was furious every time that proved to be untrue.”

A painful childhood

If Lear was fascinated by the American nuclear family, it might have been because his own childhood differed so dramatically from the norm. Born in New Haven, Conn. on July 22, 1922 to Jewish parents, he was 9 years old when his father, Herman, was arrested for selling fake bonds. While his mother, Jeannette, retained custody of his younger sister Claire, Lear was shuffled from uncle to uncle before ending up with his grandparents. Herman, for his part, had already made an indelible impression on his son. “When I was a boy,” Lear wrote in Even This, “I thought that if I could turn a screw in my father’s head just a sixteenth of an inch one way or the other, it might help him to tell the difference between right and wrong.” Herman would become the model for Archie, a delusional dad whose character would actually yield to Lear’s tinkering.

The young Lear attended Emerson College in Boston but dropped out after the Pearl Harbor attack to enlist in the military, where he served as a radio operator on a B-17 bomber. (“I wanted to be known as a Jew who served,” he said in the 2014 doc Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You.) Back at home, he married the first of his three wives, Charlotte Rosen; the couple’s daughter, Ellen, was born in 1947.

Breaking comedy ground

Lear got into comedy writing on a lark with his cousin’s husband, Ed Simmons, and spent the ’50s writing for performers like Martin and Lewis on such classic TV variety programs as The Colgate Comedy Hour and The Tennessee Ernie Ford Show. He graduated to movies in the mid-’60s, with notable credits including the Dick Van Dyke vehicles Divorce American Style, which earned him an Academy Award nomination, and Cold Turkey, which he also directed.

The sensation that was All in the Family shifted his attention to TV for the entirety of the decade that followed. But it wasn’t an instant hit. CBS aired the premiere with a disclaimer warning that the show “seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show—in a mature fashion—just how absurd they are.” Even at the height of his influence, Lear had to fight network executives over his shows’ frank treatment of issues that, he often pointed out, were already being discussed in households across America. Certain that if he capitulated once the suits would walk all over him, he stood firm. And the public responded to his candor. At one point, he had nine shows on the air, the strangest of which was the ahead-of-its-time syndicated soap-opera parody Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, with Louise Lasser in the titular role. His influence ran so deep that Richard Nixon put Lear on his notorious Enemies List. And when All in the Family won seven awards at the 1972 Emmys, host Johnny Carson joked, “Welcome to an evening with Norman Lear.”

Those exhausting ’70s took their toll. Lear had wed Frances Loeb—a feminist in a similar vein to Maude and the future publisher of the magazine Lear’s—after the dissolution of his first marriage, in 1956. They soon had two daughters, Kate and Maggie, but his nonstop work schedule took him away from both his children and Frances’ struggle with bipolar disorder. (The couple divorced in 1986, following several years of separation.) Scaling back his TV commitments—but still serving as executive producer of films like The Princess Bride and Fried Green Tomatoes—he shifted his focus to politics and philanthropy.

Philanthropy and politics

Concern over the rise of the religious right led Lear and Texas Congresswoman Barbara Jordan to found People for the American Way in 1981, an organization dedicated to fighting right-wing extremism. He sparred with Ronald Reagan in Harper’s, insisting that “without freedom from religion we would have no freedom of religion. Because the very essence of freedom is the ability to say yes or no.” Jerry Falwell labeled him “the No. 1 enemy of the American family in our generation.” Lear purchased a rare original copy of the Declaration of Independence and, in the early 2000s, took it on tour in an effort to encourage participation in the democratic process.

As a philanthropist, Lear was part of the cheekily named “Malibu Mafia,” a group of wealthy Jewish men who donated to progressive causes including nuclear disarmament, a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict and various Democratic campaigns. He used the sizable fortune he amassed in television to endow the Lear Family Foundation, which funds the Norman Lear Center for the study of entertainment, media and society at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication, as well as a raft of arts, environmental, healthcare and activist organizations.

In 1987, he married filmmaker and activist Lyn Davis Lear, with whom he remained until his death. The couple co-founded the Environmental Media Association, an organization that promotes conservation in the entertainment industry, and raised three children: Benjamin, Madeline and Brianna.

His lasting legacy

By the beginning of the 2020s, Lear had been an elder statesman for many more decades than he had been a young upstart. “Suddenly I walk into a room, they're ready to applaud,” he told TIME in 2013, by way of explaining what it was like to be 90. “I'm told how great I look all the time, and they don't mean beautiful. They mean, You're alive.” Along with an armload of Emmys, he collected a Peabody Award for Family, a National Medal of Arts and, in 2017, saw his career celebrated at the Kennedy Center Honors. He was among the first inductees into the Television Hall of Fame, as part of a cohort that included Lucille Ball and Edward R. Murrow. And, in 2019, he co-hosted and helped to produce Live in Front of a Studio Audience, a pair of hit ABC specials that staged recreations of Family, Good Times and The Jeffersons episodes.

Yet what was even more remarkable about Lear’s later years was watching his influence spread to younger creators of all identities and backgrounds, amid a contemporary America that might be even more polarized than it was during the Nixon years. Black-ish creator Kenya Barris has praised the way Lear’s shows “were poignant and had a point of view and had something to say, whether you agreed with it or not.” Lear befriended comedian Jerrod Carmichael, whose frustratingly short-lived NBC sitcom, The Carmichael Show, wore his predecessor’s inspiration proudly. Lear even returned to TV to collaborate with Gloria Calderón Kellett on a 2017 reboot of his 1975 comedy, One Day at a Time, which starred Bonnie Franklin as a divorced woman starting over with her two daughters. This time, the family was Cuban American: The mom (Justina Machado) was a veteran, Rita Moreno played the fabulous grandmother and scripts took on contemporary issues from gender identity to gentrification. When Netflix canceled the show in 2019, Lear took to his surprisingly active Twitter account to pose the question: “Is there really so little room in business for love and laughter?” (One Day was subsequently revived on Pop TV, where it ended its run in 2020.)

Like Lear’s greatest creations—Archie, Maude, George—Machado’s and Moreno’s characters can be tough or ignorant or stubborn on the outside. But they can be sweet, vulnerable and, yes, lovable below the surface. That doesn’t excuse their shortcomings, but it does make them capable of change and, thus, worth half an hour of our primetime attention. “I consider myself a writer who loves to show real people in real conflict with all their fears, doubts, hopes and ambitions rubbing against their love for one another,” Lear told TIME in 1976. “I want my shows to be funny, outrageous and alive. So far, so good." 43 years later, the assessment holds up.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com