It was easy to miss, amid the horrors, what answered them. In the blood-soaked weeks that started on Oct. 7, the most consequential acts in Israel and in Gaza may also have been the least noticed, carried out not by those who claimed leadership but by those whom leaders had failed. The people who pulled others out of rubble, or out of hiding, who sheltered strangers, who bent to heal wounds seen and unseen, they all answered unspeakable violence with a shared humanity. But their selflessness did more than save lives. It illuminated the connection at the heart of a contest that has preoccupied the world for most of a century, the fellow feeling that defines a community and, more broadly, a nation. Amid the negation of war, and in the absence of a state, two nations were affirmed.

In Israel, the absence was temporary but catastrophic. As Hamas terrorists marauded across the country’s south, killing 1,200 people in a day and retreating back to Gaza with hundreds of hostages, the Israeli government was simply not in evidence. Into the void surged the people of Israel. Within hours, a matrix of volunteers mobilized to rescue those stranded in safe rooms, sustain those evacuated from border areas, and address the traumas of survivors.

The effort was instant, intuitive, unrequested. Its leaders were citizens who had spent the prior 10 months organizing weekly protests against an extremist government angling to erase the only check on its power. Pivoting from protest to service, the loose network of citizens dispatched trauma kits and therapists. When it emerged that no one, least of all the authorities, knew who was dead, who was alive, and who had been abducted, computer experts by the hundreds dove into a digital netherworld, sleuthing for clues.

And just as Hamas made no distinction among the people it slaughtered and stole—Jews, Bedouins, the Palestinian citizens once known as Israeli Arabs, Thai guest workers hired to toil in fields—all of Israeli society reached out. A citizenry riven by inequity and political crisis assembled in the collective spirit that defined Israel at its founding. “We see this as a restatement of the country,” said Gigi Levy-Weiss, a tech entrepreneur who helped organize the response at the Tel Aviv convention center, where as many as 15,000 people showed up with strollers, paper towels—everything, really. “There is a new core.”

In the Gaza Strip, the government stayed gone. Palestinians have no state, but in the Strip the Islamic Resistance Movement, better known as Hamas, has held power for the past 16 years. After the Israeli military began its retaliatory strikes, however, the group’s political apparatus proved as elusive as its armed wing.

“There is no police station, there are no municipalities ... There’s almost nothing,” says Amir Hasanain, a 21-year-old student in Rafah who, like uncounted others, responded by assuming the duties of wartime public servant. Organizing themselves into what he describes as “a simulation of government,” the volunteers delivered basic goods to sustain a civilian population suffering bombardment and homelessness. In the first eight weeks of the assault, nearly 16,000 of Gaza’s 2.3 million residents were killed, according to the Gaza Health Ministry. Some 1.9 million were forced to flee their homes, the United Nations reported.

The uprooting evoked what Palestinians call the Nakba, or “catastrophe,” that transformed a narrow enclave beside the Mediterranean into one of the world’s most densely populated places, its numbers swollen by refugees from villages lost to Jewish forces in the 1948 war that created Israel. Defending itself in the decades that followed, Israel would occupy and then settle both Gaza and the West Bank (leaving Gaza in 2005). In those same decades, the Palestinian identity took root. Claimed by some 14 million people globally, it is grounded not only in geography and shared experience but also in the aspiration to what the U.N. Charter declares the right of any people: a state of their own.

“What is so inspiring is the communalism,” says Ghassan Abu-Sittah, a British Palestinian physician who hastens from his London practice to Gaza whenever there is a war. If the destruction and death of this one is unprecedented, he says, so is the selflessness. “Everything is being shared,” he says, “and that’s what is keeping society from collapsing. Nobody turns anyone away.”

As entire neighborhoods were flattened by bombs, whole new cities sprang up beneath tarps and blankets. Rida Thabet was the principal at a 500-student vocational college, the Khan Younis Training Centre, built and run by the United Nations Relief Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA). But on Oct. 13, the day the Israeli military ordered the Strip’s northern half emptied, Thabet effectively became a mayor, 40,000 people having crammed into the school grounds. “It’s like a city,” she says.

Thirty babies had been born there by late November. Women who gave birth during daylight hours could find help at the shelter’s three medical posts. At night, Thabet recruits volunteer medics from the tents. Mohammed Bardaweel spent most of his career in emergency rooms but now does what he can with a kit from the World Health Organization. The hardest cases arrive from the north. One woman came by foot a day after a cesarean section. Another arrived with a 6-year-old with sepsis from a wound caused by phosphorus munitions, he says. “I hope that the nations all around the world who believe in peace and human rights will try to end this war,” the physician says. He pauses before adding, “I know that nations are different than governments.” By the evidence at hand in both Israel and Gaza, it’s a distinction that might inspire hope. —With reporting by -Leslie Dickstein/New York •

Trauma Teams

Merav Roth

It turns out that just as in a murder investigation, the first 48 hours are also crucial in the treatment of emotional trauma. Merav Roth pointed this out in a video call to fellow mental-health professionals the day after the Hamas massacre. “The psyche asks, Am I supposed to collapse?” she recalls. “Is there anything to hold onto? And if you come immediately with an answer, saying, ‘Hold my hand,’ you can bring the life instinct into service, and begin to put yourself together again.”

Therapists now double as first responders in Israel. Ofrit Shapira-Berman runs a WhatsApp group that within three minutes, and sometimes 50 seconds, matches a psychoanalyst with a trauma survivor, drawing from a list of almost 500 volunteers. Many provide a lifetime of analysis at no charge. “When someone loses someone that he loves, he sort of moves to another continent; there is a continent of bereaved people,” Shapira-Berman says. “This is not a continent. It’s a planet.”

At a lushly bucolic event center north of Tel Aviv, survivors of the Nova music festival, where more than 350 were killed, gather each afternoon and evening for what looks like a lawn party. “There’s so much science on how nature heals,” says Lia Naor, who created the retreat. Survivors steer their therapy by answering the question, What do you feel like doing? There’s music, beanbag chairs to hang out in, a sound bath. There are therapists too. “But they’re not on you,” says Liam Kedem, 24, who ran six miles from Hamas gunmen and comes to the retreat every day. “What makes me really feel like recovering is just sitting with the friends that I’ve been in the situation with. In the city, people look at me with these sad eyes.”

The approach, which seems perfectly suited to people who would attend a rave, can be adapted to meet anyone where they live. “We’re 9 million people in trauma. It’s not one or two,” Naor says. “So the only way to treat is within community.”

The Hamas massacre also activated the 2,000-year communal history of persecution every Jew carries. “We are so trained in trauma,” says Roth, a psychoanalyst and professor at the University of Haifa. “I was raised into the Holocaust.” But if Holocaust survivors were shunned in Israel in the 1950s as damaged or weak, subsequent generations have learned to appreciate the experience of victims and make common cause with their grief.

At the Dead Sea hotel where survivors of the Be’eri kibbutz are lodged, Roth met a woman of 85, who “was black with her death wish. She said, ‘I don’t want to live in such a world.’ And I said, ‘Please look around you for a second. Is this the world you want to leave?’” The sprawling resort was jammed with all manner of goods donated from around the country. “Her eyes filled with tears, but loving tears. And she said, ‘It’s so amazing. From the first moment, people came, and came with everything that we need.’”

“Solidarity,” Roth says, “is a cure.”

Night Medic

Lana Okal

At the shelters where most of Gaza’s residents now reside, there are shortages of almost everything except people. But that can be a blessing, as they bring expertise. When Lana Okal arrived at the Khan Younis Training Centre camp she announced that she was a doctor. The 25-year-old had graduated in January from Cairo University’s Kasr Al-Ainy School of Medicine, an experience she savored after life in Gaza. Her hope was to study in Britain after completing a year interning at Gaza City’s Al-Shifa medical center. She had two months left when the war began. “We had yet to cover anesthesiology and emergency medicine,” Okal says.

She was put to work. By day, she has helped record the health status of the displaced people in the shelter. At night, she is on the list of medics who have volunteered to be roused in emergencies. Trained in primary care, Okal felt useful treating most of the patients brought to her. But one night in late November, she found herself facing a 40-year-old woman who had been pushed in a wheelchair from Gaza City with her children. Her leg had been amputated after being crushed in the bombing; her husband was dead; and the young physician felt as overwhelmed as the Gaza health care system itself. “She said, ‘Help me.’ I cannot. I want to try, but I cannot.” The amputation was “very polluted,” Okal says, and she had neither the equipment nor the expertise to treat it. Cell networks were down, so no ambulance could be summoned. “The situation here,” Okal says, “is very difficult.”

Peacekeeper

Amir Badran

Before there was Tel Aviv, there was Jaffa, an ancient city with the cosmopolitan feel of a Mediterranean port and a population to match: a third of the city are Palestinian citizens of Israel. That might explain Amir Badran’s presence on the Tel Aviv–Jaffa city council. But only faith in human nature could account for his decision this fall to run for mayor just two years after Israel’s “mixed cities” erupted in street fights.

Watching the news on Oct. 7, Badran knew his campaign was in trouble. But he held out hope for Jaffa. With a few phone calls, the attorney founded the Guard for Jewish-Arab Partnership, a joint effort to keep the peace. It advertises and staffs a hotline, sends volunteers to escort people who feel unsafe, and partners with Standing Together, a nationwide solidarity effort. Fear is all around. In the month after the massacre, as many Israelis applied for gun permits (236,000) as had done so in the previous 20 years. Jaffa Arabs like Badran who were appalled by the Hamas massacre were also shaken by Israel’s retaliation. Some 200,000 residents of Gaza trace their families to Jaffa, the home they fled or were expelled from in 1948.

“We will work together, Arab and Jewish residents, to keep each other’s backs,” Badran says, “to be safe in our homes, to secure our mosques, synagogues and churches, and to show the world that we can do it differently, while other people speak in the language of war, especially the mixed cities.” Regaining that equilibrium, he says, is the only way forward for a country where 20% descend from Palestinians who stayed within Israel’s borders in 1948. “The reality is that we are living together, and we will have to still live together.”

Giving Shelter

Rida Thabet

For most people in Gaza, the war is a saga of exodus into smaller and smaller spaces. More than 1.6 million of its 2.3 million residents have been forced from their homes, first into the southern half of the Strip, then into the cramped lots where 1.4 million have sought refuge under the blue flag of the U.N. Some 40,000 are camped in the vocational college run by Rida Thabet.

Their hardship is more than a humanitarian challenge for Thabet; it is a personal one. “I’m displaced myself,” she says. She hails from Gaza City, from which people still arrive, sometimes wounded, always stressed. “They see us as management,” Thabet says. “They come with anger, and they throw that anger on your face.” The face is sympathetic. Thabet comforts not only her 15-year-old daughter, traumatized by the cascades of bombing, but also her guests. On Nov. 24 the oldest was the 95-year-old woman who asked, as she does daily, “Where am I? Who are you?” The youngest was just hours old.

“You want to help but you feel helpless,” says Thabet. Her answer is action: finding mattresses for those at risk of bedsores, tarpaulins for people sleeping in the open, common ground for feuding spouses, and support groups for children who have seen too much. As an employee of UNRWA, which in peacetime provides schools, medical services, and aid to the 74% of Gazans who are registered refugees, Thabet is both an anchor of Gaza’s middle class, and a conduit for the trickle of assistance reaching them. More than 100 of her colleagues have been killed, including a friend who died “giving training on how to keep safe.” “We have some unique stories,” Thabet says. “Some of them are very sad ones. And some can give hope.”

Brothers and Sisters for Israel

Ron Scherf

Few societies are built around the military the way Israel is. So it made sense that the largest protests against Benjamin Netanyahu’s efforts to sideline the judiciary earlier this year were led by a group called Brothers and Sisters in Arms. Started by seven military reservists on WhatsApp, it grew to 50,000 members, many of whom vowed not to serve in protest of the Prime Minister’s power grab.

When Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, the group nonetheless urged its members to report for duty “without hesitation.” But the real surprise was that it stepped in for a government that proved unable to function. Brothers and Sisters for Israel, as it was renamed that same day, posted an emergency button on leading news sites: “If you have an emergency, click here.” It sent 400 teams to the communities around Gaza to coax terrified residents out of safe rooms, and 5,000 volunteers to work the depopulated farms. Hospitals got help treating the wounded, evacuees got hot meals, and donations got sorted in an underground parking garage staffed each day by 10,000 to 15,000 volunteers. The Facebook post “Can we just pay taxes directly to Brothers and Sisters in Arms?” became a meme. “You see the power of unity,” says Ron Scherf, a co-founder. “Everybody’s now focusing on helping each other.”

Three weeks after the massacre, the situation room at the Tel Aviv convention center was still humming. A computer whiteboard listed 60 teams, ranging from intelligence to kindergartens, other protest groups having pivoted just as nimbly to whatever needed doing. (A lawyer previously tasked with springing arrested protesters had organized the retrieval of pets from evacuated towns.)

Information scholar Karine Nahon led the effort to sort the dead from the abducted, a daunting task that began with 14,500 names. Some 500 volunteers crawled through social media feeds and 150 Hamas Telegram channels, deploying facial-recognition software and novel algorithms. “We’re a small country,” Nahon says. “We gave a call, and everybody showed up.”

Eyal Shai, an air force reservist with experience running giant call centers, organized the teams. “They’re talking in systems,” he says. “I’m talking people and jobs.” Every hour, a table of volunteers would break to talk with a psychologist. Few knew each other by name, but many recognized each other from the protests that, at the time, had felt like the most important task at hand. “When you look at the motive for our behavior over the last year, it all came from being patriotic,” says Oren Shvill, another of the founders. “True love of country.”

Civil Defender

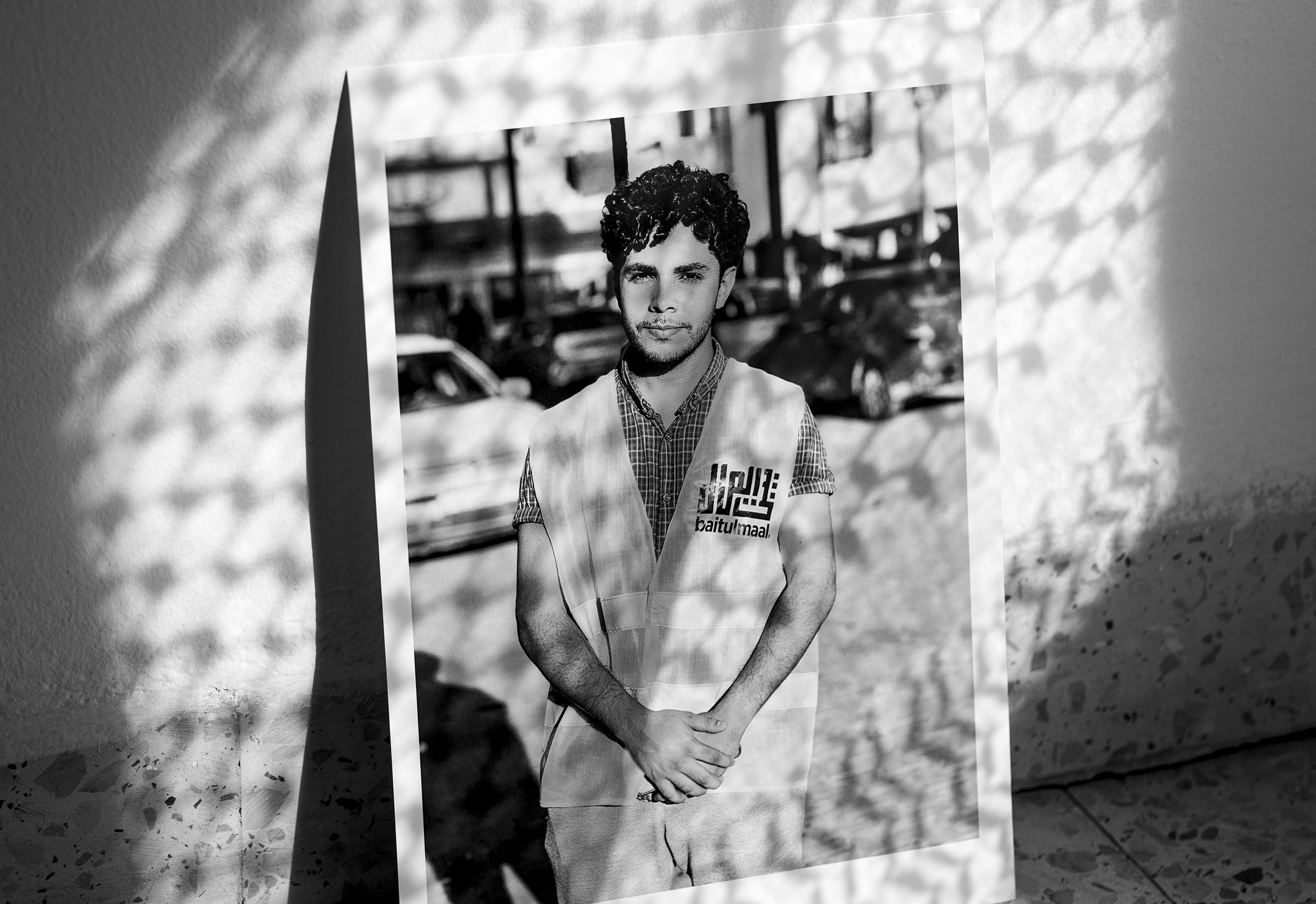

Amir Hasanain

The future of any society relies on the likes of Amir Hasanain. The résumé of the 21-year-old student is a ladder of civil-society internships and academic scholarships capped by a semester at Missouri State University, sponsored by the U.S. State Department. Hasanain was back in Gaza doing his final undergrad year when Israeli bombs flattened Al-Azhar University. “I have witnessed a lot of things,” Hasanain says. Many are horrible, like “the scream of my little brothers and sisters every time there is an airstrike.” In the first days of the bombardment, the entire family gathered in one room so “we all die at once, and none has to regret his survival.” But he has also witnessed the owners of private wells opening them to all. Those with solar panels charge phones for free. Police stations are not operating, but “elderly people in the neighborhood volunteer to solve the quarrels that arise between neighbors,” he says. “The government is now dysfunctional,” he notes, but the people have stepped up.

Hasanain himself rises at 6 a.m. at his home in Rafah, near the Egyptian border, and walks first to the market and back, then two kilometers to wait four hours for water. He rides a donkey cart to where he volunteers delivering food or other aid via the civil-society organizations that are like the passersby who, in the absence of civil-defense workers, scramble into the rubble in search of survivors. Walking two kilometers home, Hasanain eats his one meal of the day. After two months of war, though, the real concern is mental stamina, he says. “The days are just overlapping with more fear, disappointment, and frustration.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Introducing TIME's 2024 Latino Leaders

- How to Make an Argument That’s Actually Persuasive

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- The Ordained Rabbi Who Bought a Porn Company

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

- The 100 Most Influential People in AI 2024

Write to Yasmeen Serhan/London at yasmeen.serhan@time.com