Beneath the bluster over what’s taught in schools is a struggle over the future of justice itself. Pressure to remove topics like mass incarceration from school curricula in places like Florida and from the College Board’s Advanced Placement (AP) African American History course reveals precisely why we must continue teaching it. Those pushing censorship are afraid of mass incarceration for the same reason they’re afraid of the history of slavery: Because reckoning with these histories raises the moral imperative to repair them.

I’ve been teaching the history of mass incarceration at the high school and college levels for over a decade now. The things that the African American Policy Forum identify as targeted for removal from curricular and state standards are at the center of my own pedagogy, namely, instilling a broad understanding of the strategies Black communities have employed to combat the effects of inequality locally and abroad. And, above all, helping young people, “articulate Black experiences and perspectives to create a more just and inclusive future."

Mass incarceration is the clearest afterlife of slavery. The exception for “slavery and involuntary servitude” to continue to be used as punishment for crime was reinscribed in federal law following slavery’s formal abolition. This was used effectively to re-enslave Black people, particularly in the South, during the subsequent “convict leasing” era, what W.E.B. DuBois dubbed the “spawn of slavery.” Federal, state, and local policies perpetuated racism in the prison system from 1865 until 1925, otherwise known as the convict leasing era, through the Civil Rights-Black Power era, and racial criminalization reached another nadir in the “tough-on-crime” and War-on-Drug eras. The rise of mass incarceration was marked by skyrocketing rates of imprisonment, growing by 400% from 1970 to 2000, and racial disparity, as police continue disproportionately to stop, shoot, and imprison Black Americans.

Young people must be allowed to wrestle with past injustice if they are to participate in building a more equitable future. And while the harms of slavery and racial oppression occurred in local, state, and national contexts, they also have crucial global dimensions. My own research has shown that mass incarceration arose from slavery and successive eras of empire building across continental North America, the Caribbean, and Pacific Oceans. The Black chain-gangs of the deep South appear little different from the Black road-gangs in the Panama Canal Zone during the same period. Plantation labor on Parchman Farm in Mississippi was not unlike the forced labor at the Iwahig Penal Colony in the Philippines, said to be the largest penal colony in the world by the 1920s. Even as mass incarceration has come to be seen as an unjust and oppressive system domestically, the U.S. continues to export its model of incarceration—with the globalization of super maximum security prisons—around the world.

Read More: How Community Health Workers Can End Mass Incarceration and Rebuild Public Safety

We are living in a world created by slavery and colonialism, still dominated by “global racial empire” as philosopher Olufemi O. Taiwo puts it. Because the root causes of oppression and injustice are global, so must be efforts to repair the harms. For Taiwo and generations of reparations activists, this requires nothing short of remaking our entire economic, political, and social systems locally and globally: beginning with climate justice, continuing through international distributive justice, striving for a global community structured by non-domination.

Teaching a global perspective not only increases the urgency of these questions, it can actually offer a wider range of alternative solutions to them. Black-led social movements recognized this. Members of the Black Panthers saw how their communities were governed like internal colonies, and how overseas colonies were treated like geographic prisons. Many of the same intellectuals and activists on the frontlines of protesting prison imperialism, also developed plans for repairing the harms of slavery and unjust imprisonment. These proposals for reparations drew on an expanded human rights framework and have always been about achieving a measure of self-determination and healing: combining demands for social justice, dignity, money, and land to create new modes of improving community life, both locally and globally.

These are precisely the kind of big historical and contemporary questions young people yearn to grapple with. They are as real and complex as their own lives, and stretch their imaginations and capacities to care. Discussing the history of mass incarceration in schools, when thoughtfully implemented, has real, tangible benefits. This is an issue that touches the lives of every student, their family members, or someone they know. There are now an estimated 70 to 100 million people living with criminal convictions.

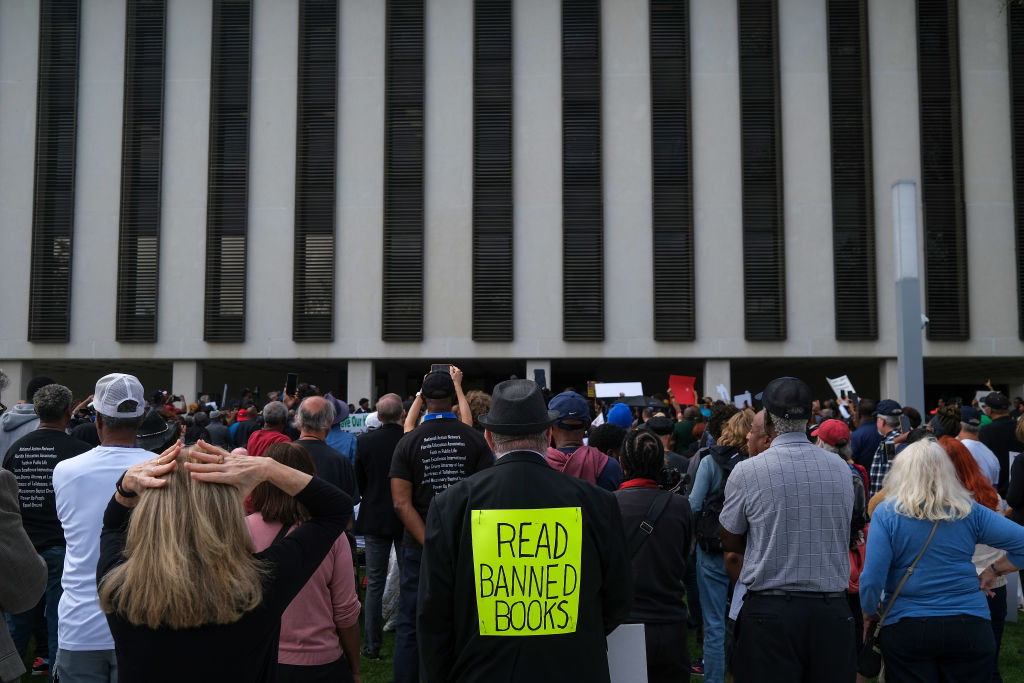

The recent groundswell in local, state, and national reparations proposals aim to redress the harms of unjust, racially targeted mass incarceration along with housing, health, and wealth inequality in places that have passed reparations plans like Chicago and Evanston, Illinois, Rosewood, Florida, Ashville, North Carolina, and Providence, Rhode Island. In California, the state Reparations Task Force requires recommendations to comport with international standards for redressing wrongs and injuries caused by the state, such as the United Nations’ Principles on Reparation. It calls on us to learn from the precedents set in Germany, Chile, South Africa, and Canada. While racial equity projects can be undertaken at the local and state level, achieving reparations cannot be done piecemeal in isolated localities. It requires the whole country. But how are young people and their families expected to grapple with these issues if the very topics of mass incarceration and reparations are banned from schools?

We are only beginning to imagine what it will mean once young people dig into these dimensions of the past to implement their local and global visions of repair. Just as racial injustice and oppression crisscrosses borders, so must the healing journey.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com