It’s not as if Saturn needed any more kids. The ringed planet already has 53 known moons and 9 more candidate ones—putting it just two shy of 64, which would make it kind of an octo-octo-mom. That’s an awfully big shopping bill when it’s back to school time.

But Saturn apparently can’t help itself, and according to new findings by NASA’s Cassini-Huygens space probe just published in the journal Icarus, baby number 63 may be being born.

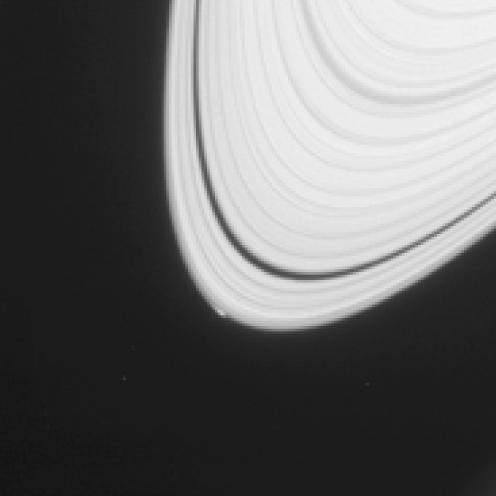

The new arrival has not been spotted directly yet. What Cassini, which has been orbiting through the Saturnian system since 2004, has seen instead is a sort of bulge in Saturn’s A Ring—the outermost of its larger, brighter bands—that measures 750 mi. (1,200 km) long and 6 mi. (10 km) wide. The rings — made of ice, rock and dust — are believed to be the nurseries in which all of the moons were born, with material coalescing and clumping, adding more mass and thus more gravity, and growing bigger still. The new moon—if it exists—is a pipsqueak, perhaps only 0.5 mi. (0.8 km) in diameter, somewhere within the 750-mi. clump, though there’s no telling exactly how large it will get.

As befits something so little and—if you’re an astronomer—irresistibly cute, the moon has been given a nickname: Peggy. It will eventually be given a formal name, but that will only be after it has, effectively, grown up and left home.

“We have not seen anything like this before,” said astronomer Carl Murray, the lead author of the Icarus study, in a statement. “We may be looking at the act of birth, where this object is leaving the rings and heading off to be a moon in its own right.”

If so, Peggy could represent the end of the line. Since the largest of Saturn’s icy moons are located furthest from the planet, the belief is that they are also the oldest, growing bigger and bigger and moving outward as they did. The formation of those big siblings as well as all of the smaller ones is believed to have depleted the rings of much of their moon-forming raw material. What’s left is enough to keep the overall ring system alive, but not enough to allow the emergence of any more moons. At 4.5 billion years old, Saturn may at last be ending its child-bearing years.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com