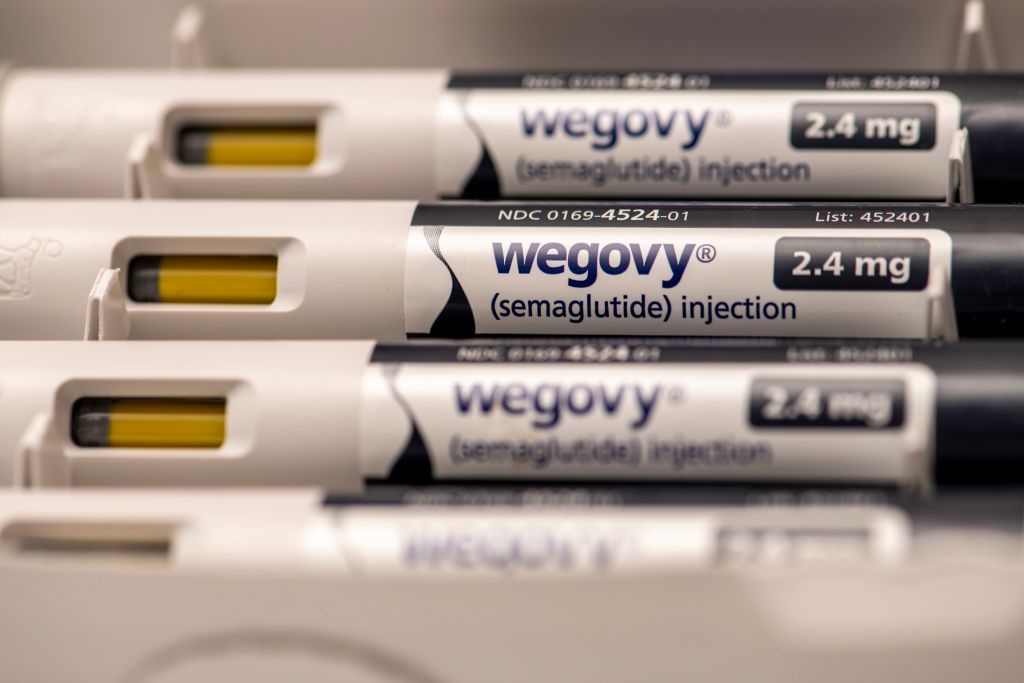

Popular weight loss drugs have dominated news headlines and social media, mostly for their ability to help people shed pounds and control diabetes. But now there is evidence that one of the drugs, semaglutide, can also help reduce the risk of dying from heart disease in some patients. The drug semaglutide is sold under the brand names Wegovy, Ozempic, and Rybelsus. This trial, however, only studied the effects of Wegovy, which is semaglutide at 2.4mg in injectable form, and currently approved for weight management. The results of a much-anticipated study, sponsored by semaglutide’s maker Novo Nordisk, investigating the drug’s effects on the heart were presented at the annual meeting of the American Heart Association in Philadelphia and published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study involved more than 17,000 people without diabetes but with a history of heart attack, stroke, or circulatory symptoms, who were also overweight or obese, with a body mass index of 27 or greater. Because they had a history of heart issues, most were on medications to treat risk factors like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and clotting. To learn what effect losing weight could have on reducing the risk of dying from heart disease—on top of controlling those risk factors—the researchers randomly assigned half of the volunteers to receive the drug semaglutide, which was approved in 2021 to treat people who are overweight and obese, while the other half received a placebo.

After more than three years, the scientists, led by Dr. A. Michael Lincoff, professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, found that the people who received semaglutide lost about 9% of their body weight, compared to less than 1% in the placebo group. Those receiving semaglutide also reduced their risk of having a heart attack or stroke, or dying from a heart event, by 20%, compared to those receiving the placebo. The result generated applause from the standing room-only audience packed into one of the main auditoriums for the American Heart Association meeting.

“It’s been established that obesity and being overweight increases the risk of cardiovascular events, but while the standard of care includes treating risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol with medications, the risk factor of obesity and being overweight have not been something we have been able to effectively treat in the past,” Lincoff tells TIME. “Now for some patients we have another pathway, an additional modifiable risk factor that can be treated with semaglutide.”

“This is an entirely new pathway to harness, of addressing obesity and its metabolic complications,” says Dr. Amit Khera, director of the Preventive Cardiology Program at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. “The fact that we have a new treatment avenue for patients with cardiovascular disease is incredibly exciting, and welcome.”

“The results are astounding,” says Dr. Holly Lofton, director of the medical weight management program at NYU Langone Health, who led the study at one of the more than 800 sites involved in the trial. “I think this will change prescribing practices.”

The patients in the study represent a larger cohort of 6.6 million people in the U.S. who might benefit from the drug, said Dr. Ania Jastreboff, associate professor of medicine and director of the Yale Obesity Research Center at Yale School of Medicine during a presentation at the conference.

Lincoff notes that while the trial found a link between the weight loss drug and a lower risk of heart events, the effect may be more complex than a simple correlation between pounds dropped and risk lowered.“It isn’t the amount of weight loss that influences [heart] risk,” he says. The difference in heart events between the two groups began to emerge quickly, after about a month of weekly treatment, but the weight loss occurred gradually and didn’t max out until about a year. “The benefit was not necessarily proportional or driven by how much weight was lost,” he explains. In fact, the heart benefits were similar for people no matter what they weighed at the start of the study, or how much they lost during the trial.

More research will be needed to clarify exactly how the drug is affecting the heart, but it’s possible that changing levels of GLP-1 could also trigger physiological changes that directly affect the heart. “We know from other studies that excess adiposity can have direct effects on heart and blood vessel cells, so the drugs may be affecting excess fat cells, which promote inflammation and can promote atherosclerosis and increase the stickiness of blood [through clotting], all of which increase the risk of heart events,” says Lincoff.

Jastreboff agrees. “If we treat obesity, then we improve things like hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and inflammation, and we see benefits for all different types of diseases,” she said during a briefing at the conference.

The data provides the strongest reason yet to start treating heart patients who are overweight or obese, just as doctors address high blood pressure, excess cholesterol, and diabetes in patients. “It’s always nice to have another tool in the toolbox,” says Dr. Sean Heffron, assistant professor of medicine at the NYU Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Many heart experts are impressed that the 20% drop in heart events was on top of reductions they already experienced from being treated with the current standard of care, including aspirin, statins to lower cholesterol, and medications to control hypertension. “We are literally leaping forward from the past to the future at a watershed brought on by highly effective obesity medications,” Jastreboff said.

Dr. Bruno Manno, a clinical professor of cardiology at NYU Langone who was in the audience for the presentation, says “I see about 20 people a day, half of whom would qualify for this [treatment]. The results make a very compelling argument for sure for treating them.” He says, however, that the high cost of the drug—more than $1000 for a month’s supply—as well as lack of coverage by insurance companies and shortages in the supply of semaglutide are the biggest barriers to seeing heart patients benefit from the medication. “If the cost and availability issues weren’t there, there wouldn’t be an issue at all in treatment of the people who are a fit for this medication,” he says.

One change that could potentially convince more insurers to cover the drug is adding heart benefits to its label. Novo Nordisk has filed a request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to update the label for semaglutide (Wegovy) to include the fact that among people with a BMI of 27 or higher, and with a history of heart disease, the medication can reduce the risk of additional heart events. The FDA has granted priority review of the request, and is expected to make its final decision in six months.

In the meantime, the success of the study naturally raises the question about whether the drug should be used in people without a history of heart attack or stroke, to help them avoid a heart event to begin with, rather than withholding the medication until people experience a heart event. “Scientifically, the medical benefit is likely to be similar,” says Lincoff. “But logistically doing that study will be difficult.”

Even in the absence of such a study, Lofton notes that combining the results of this trial with the results from previous studies of semaglutide that included people who were overweight or obese without a history of heart problems, may justify using the drug to help people avoid having a heart event in the first place. “I think the astute preventive cardiologist or primary care doctor would consider that someone is a candidate for semaglutide to help them lose weight if they are overweight or obese and have a strong family history of heart disease or other risk factors,” she says. In fact, the drug is already approved for people who are overweight or obese, but their doctors can now tell them that there is a possibility that in addition to losing weight, they might also reduce their risk of heart disease. However, there isn’t hard data to document that yet. “They may say that the drug is not intended to treat cholesterol or blood pressure or other heart risk factors, but they may also see benefits there,” she says.

As encouraging as the data is, Khera cautions that the results should be interpreted carefully, and aren’t a license to dismiss the importance of changing diet and exercise habits to lower heart disease risk. He notes that the population in the study were people with existing heart disease, but that ideally, people should avoid experiencing heart events in the first place. “You don’t want to wait until you develop cardiovascular disease,” he says. “It’s not about making a choice between lifestyle modifications or these medicines. It never is, and never will be. It should start with lifestyle changes first, and when needed, this medicine can now be a helpful additional option.”

Addressing access and availability will be the next hurdles for semaglutide. Novo Nordisk has increased manufacturing to meet the already explosive demand for the drug, but with a new population of patients now eligible for the medication, supply constraints likely won’t ease until at least 2024.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com