Surgeons at NYU Langone Health have performed what they say is the world’s first whole-eye transplant, combined with a partial face transplant, in an important step forward for the fields of both transplantation and vision restoration.

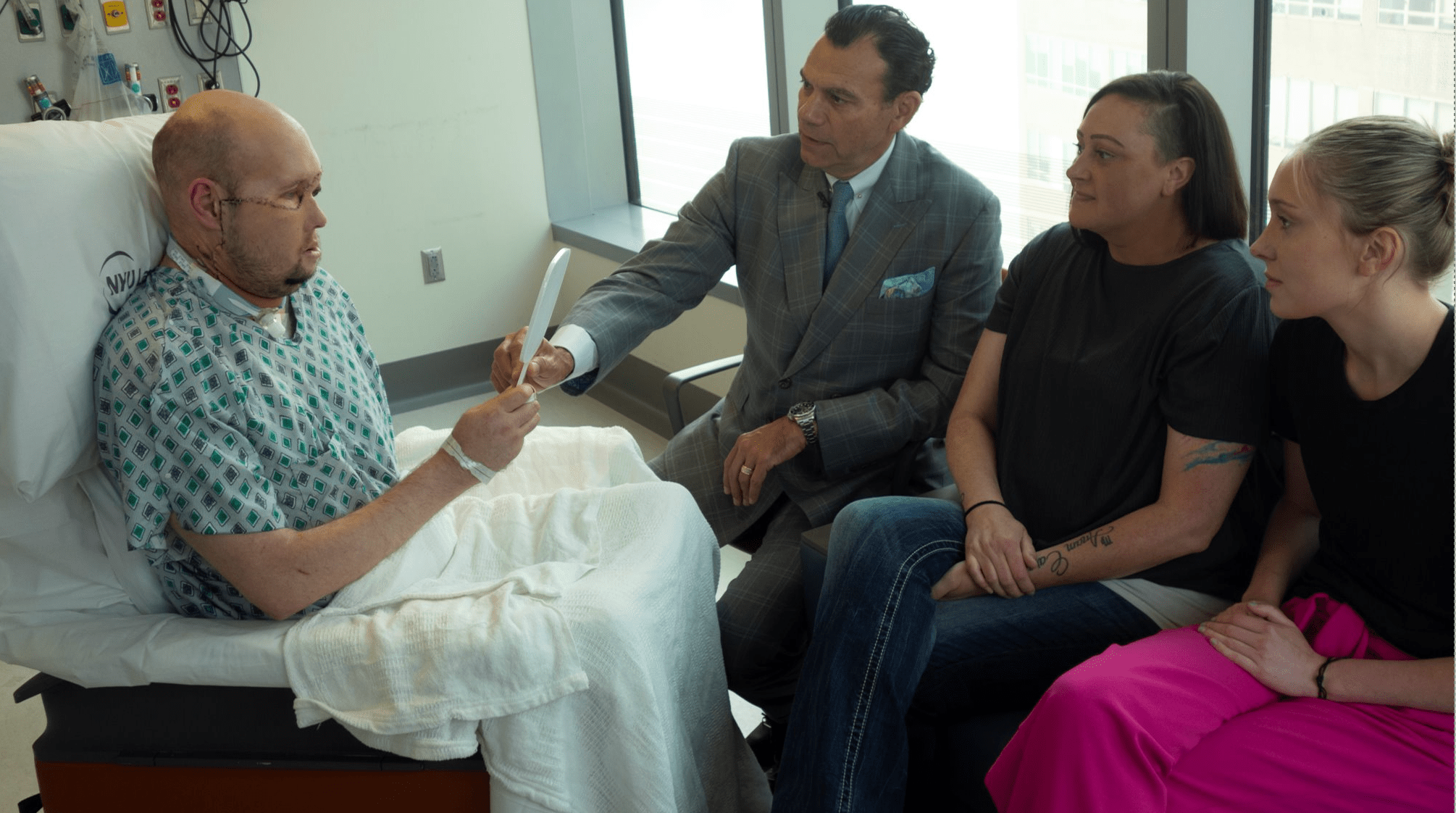

In May, a team of more than 140 health care workers performed the 21-hour procedure on Aaron James, a 46-year-old Arkansas man badly injured in a workplace accident in 2021. James, a high-voltage power lineman and military veteran, suffered a massive electric shock when his face accidentally touched a live wire on the job. James was lucky to survive, but lost his left eye, much of his face, and part of his left arm.

It’s not clear whether James will ever be able to see from his donated eye. Still, the novel combined transplant has given James major cosmetic benefits and improved his ability to speak and eat solid food—meaning that, for the first time since his accident, he’ll be able to enjoy a Thanksgiving meal with his family this year.

The nearly two years since the accident have been a test “of strength, will power, family, friends,” James said during a Nov. 9 press conference. “And I think we beat it.”

Corneal transplants are now used fairly frequently to restore vision and function to damaged eyes, and around 50 face transplants have been performed worldwide—including several by Dr. Eduardo Rodriguez, the NYU surgeon who led the team that performed James’ procedure. But, until now, a successful whole-eye transplant had never been documented. “There’s really been no [previous] attempts [of this procedure], whatsoever, as a human clinical trial,” Rodriguez said during the press conference. “It’s uncharted territory.”

There is always a risk that the body will reject a transplanted organ. But transplanting an eye involves extra layers of complexity because the organ connects to the brain, introducing serious risks, potentially including death, if something goes wrong.

Despite the challenges, Rodriguez and his team decided to attempt the procedure, with James and his family's blessing. A single donor—a man in his 30s—provided both the face and eye for transplantation. Hopes weren’t particularly high; “none of us thought the eye would even work,” Rodriguez said. But his team wanted to see what was possible.

During the 21-hour operation, which they rehearsed more than a dozen times, Rodriguez’s team injected stem cells harvested from the donor’s bone marrow into the donated eye’s optic nerve. Stem cells, the building blocks for other types of specialized cells in the human body, can work to repair damaged cells, including in the eye. Infusing the optic nerve with stem cells, physicians hoped, would increase the odds of nerve regeneration and eye function.

It’s still too early to say whether he will see from it, but James' new eye has shown signs of progress in the months since the operation. Blood now flows directly to its retina, the part of the eye that senses light and transmits those signals to the brain to create images. It also has a viable pupil.

James—who still has vision in his right eye—may never see from his left, and cannot currently open his left eyelid, but he says the surgery has already been a success to him. “When they approached me with the eye transplant and asked me if I wanted to do it, I said, ‘Of course,’” James says. “You’ve got to start somewhere.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com