For decades, multinational corporations—especially those based in the U.S.—have funneled billions of dollars in profits to tax havens, earning even more money for their shareholders.

That’s why a global agreement brokered in 2021 by the Organization for Economic Co-operations and Development (OECD) was a huge deal: it set a global minimum tax of 15% and included a few ways that countries could collect that tax even if tax havens and companies were not cooperating.

But corporations are already finding new ways to get around that agreement; a development that will end up reducing the amount of corporate taxes countries can collect by about half of what was originally expected—$135 billion annually instead of $270 billion, according to a report released by the E.U. Tax Observatory on Oct. 23.

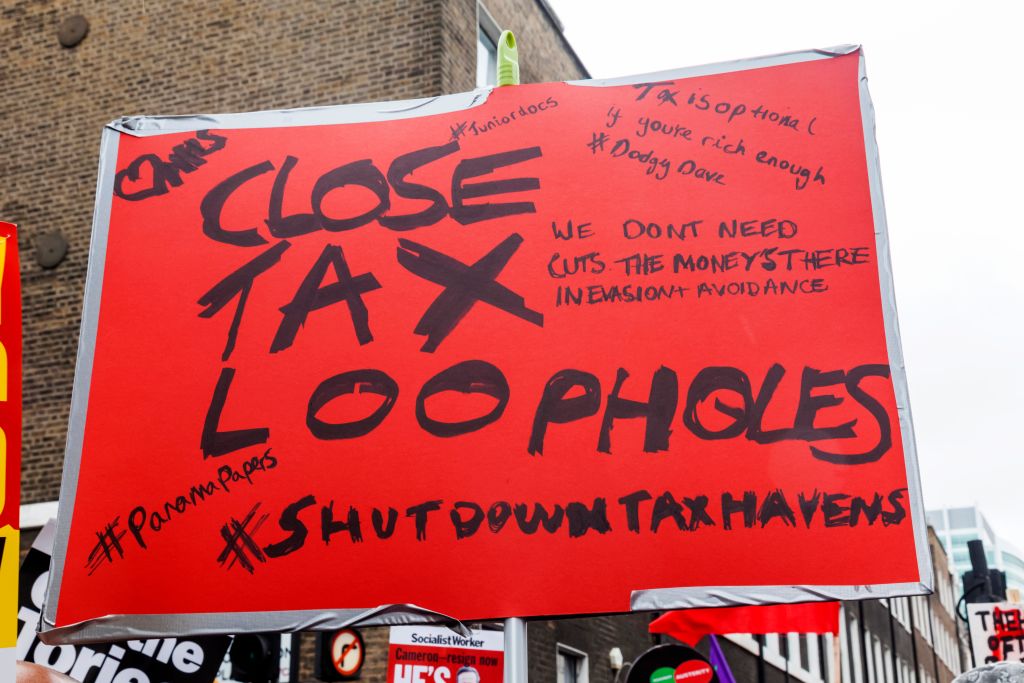

This finding is a big deal because tax evasion exacerbates global inequality, taking money that could have been used by governments for policies that improve the lives of their citizens and instead giving it to shareholders of giant corporations.

The 2021 agreement made it harder for companies to move profits to low-tax countries, says Gabriel Zucman, director of the EU Tax Observatory and one of the coordinators of the report. But instead, companies are now going to shift profits to countries that offer big tax credits or subsidies, including some in the E.U.. Governments are increasingly using refundable tax credits—such as the Inflation Reduction Act—as their new way to structure corporate tax policy, Zucman says.

Avoiding taxes is an art that companies have perfected over the last few decades. In the 1970s and 1980s, according to data from the E.U. Tax Observatory, barely any profits were shifted to tax havens, countries like Bermuda and Ireland where companies based in relatively highly-taxed places like the U.S. and Europe could move operations on paper and only pay minimal (or in some cases zero) taxes on their profits. But that changed in the 1990s and 2000s, when about one-third of the foreign profits of U.S. multinational corporations were shifted to tax havens. In 2010, U.S.-based companies began to shift even more profits—around 50%—and the level has remained elevated ever since, according to the Tax Observatory report. About $1 trillion in profits were shifted in tax havens in 2022, the report finds.

One common method of corporate profit shifting works like this: A company like Microsoft sells its intellectual property to a subsidiary in a low-tax country and then pays that subsidiary for the use of that intellectual property. The foreign subsidiary reaps huge profits that would normally show up on Microsoft’s profit ledger in the U.S. or U.K., but that instead show up in the tax haven and are thus taxed at a very low rate. This is actually a strategy Microsoft used, selling its intellectual property to a 85-person factory in Puerto Rico, where its tax rate was close to 0%, according to ProPublica. The IRS says Microsoft owes it a cool $29 billion in back taxes. In response to ProPublica's questions on the issue, the company declined to discuss details, saying only that it “follows the law and has always fully paid the taxes it owes.”

In some of the most frequently-used tax havens like Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, and Ireland, U.S. companies reported tens of billions of dollars of profit despite having few employees, according to an analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. In 2019, for example, U.S. companies reported $30.7 billion in profits in Bermuda, which accounts to about $36 million per employee there. The status quo allows multinationals “to use accounting gimmicks to report complete nonsense to their tax authorities,” says Steve Wamhoff, the director of federal tax policy at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Both the E.U. and U.S. have tried to rein in profit-shifting, knowing it was costing them billions of dollars, but no significant progress was made until the global minimum tax agreement in 2021. At the time, the OECD hailed the agreement as “ground-breaking” because it made it much easier for countries to force companies to comply. Essentially, the countries signing on agreed to set a floor so that multinational corporations would pay a tax of at least 15% in each jurisdiction where they operated. If a jurisdiction where a multinational corporation is located doesn’t tax that company 15%, the agreement makes it possible for other countries to collect that revenue.

“It’s a very well-designed mousetrap,” says Mike Kaercher, senior attorney advisor at the Tax Law Center at NYU.

There are some obstacles to effectively implementing the agreement—the key one being that every participating country has to ratify it and the U.S., one of the agreement’s biggest promoters, has not yet announced any plans to do so.

What’s more, the rule allowing participating countries to collect minimum taxes not collected by not-participating countries is temporarily suspended until at least 2026 to allow room for adoption—and, Zucman says, there is some concern that this suspension will be extended indefinitely.

Further still, in July 2023, the OECD clarified that the global minimum agreement doesn’t apply to certain tax credits, like those offered by the Inflation Reduction Act. Part of the Inflation Reduction Act allows for tax credits to be transferable, meaning a green energy firm can receive a tax credit and then sell it to another company, allowing the green energy firm to get much-needed cash and a multinational firm to get a significant break on its 15% minimum tax rate.

While for decades there was a race to the bottom between the many countries lowering their tax rates to invite foreign companies to move their profits there, now, there’s going to be a global-subsidies race targeting green energy producers, Zucman argues.

“Worryingly, the global minimum corporate tax agreement does not address this form of tax competition, and in fact legitimizes it,” Zucman and his co-authors write.

Of course, there is a positive to this new form of tax avoidance; it encourages companies to invest in green energy. But this still risks exacerbating inequality in the countries where the companies are actually operating. It could help boost the after-tax profits of shareholders at the expense of everyone else.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com