In mid-September, TIME interviewed Malaysian Prime Minister and democracy icon Anwar Ibrahim in Kuala Lumpur. After a political struggle spanning a quarter of a century defying incarceration and repression, Anwar finally took power following a highly divisive election last November. Nearly a year into the job, as the euphoria fades and the country’s favorite rebel transitions into a cautious patriarch, he is faced with the challenges of stabilizing his country’s politics, kickstarting a flagging economy, and combating a rising tide of Islamist politics that is polarizing society.

We met in the Malaysian Houses of Parliament complex, just before Anwar was to address lawmakers in what turned out to be a stormy session. The Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) staged a walkout after a heated exchange of words over allegations of judicial interference to help a graft-tainted ally. The tussle offered a peek into one of Anwar’s pressing difficulties. He has cobbled together a “unity government” of various coalitions and parties and has kept PAS, now the largest party in Parliament for the first time in Malaysia’s history, out of government. PAS, however, continues to gain ground and won more contests in state elections in August.

PAS’s rise foregrounds a resurgence of Malay-Islamist rhetoric that is polarizing Malaysia’s multiracial society. Even a non-Islamist secular leader like Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia’s longest-serving Prime Minister, who is increasingly seen on PAS platforms, now says multiracial Malaysia would be unconstitutional and charges Anwar for trying to “give this country away to outsiders.”

“Outsiders” is codeword for the Chinese and Indians, who are mainly Buddhist and Hindu. Race, intertwined with religion, goes to the heart of Malaysian politics. The majority Malays are Muslim by law and enjoy quotas in everything from university seats and jobs to business loans and housing under a decades-old affirmative action program. Malay-Islamist supremacists have been fanning their fears of losing these privileges.

We discuss this resurgence of identity politics and more—from Malaysia’s place in great-power competition between the U.S. and China, to boosting Malaysian democracy—in our frank interview.

Below are 5 takeaways from the conversation.

1. Anwar has a plan to restore democracy in Malaysia

Anwar once called Malaysia “the most tragic case” of democratic backsliding in Southeast Asia after being denied the opportunity to govern despite winning a historic election in 2018 that unseated a government led by the Malay nationalist UMNO party for the first time since independence in 1957. For him, the way to counter this regression is through a strong commitment to institutional reforms. When asked how he is restoring democracy in Malaysia, he emphasized rebuilding accountability. “Because democracy can be a farce, too. It can be a [instrument] for the rich and the powerful to manipulate. We are mindful and aware of that. Therefore, mass education to make people more aware is a major challenge. Otherwise democracy can be reduced to the establishment control of the ruling elite,” he said.

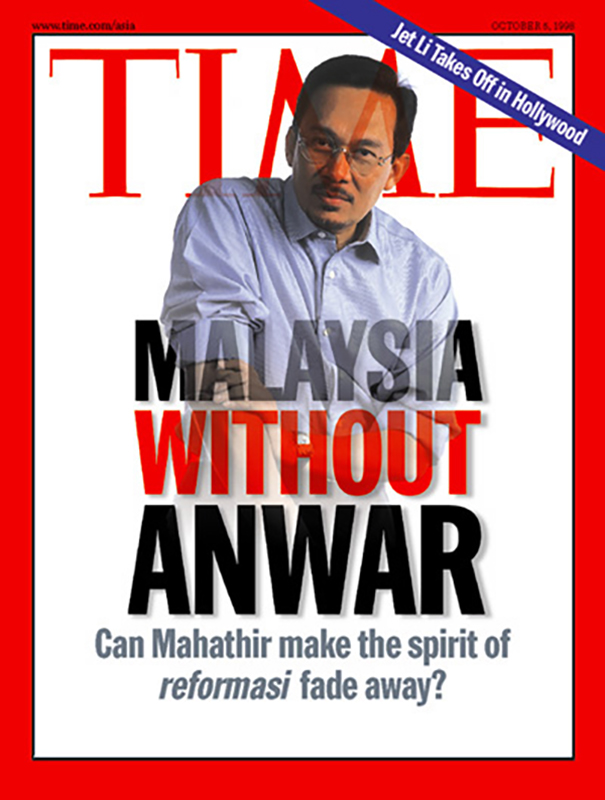

Good governance is a top priority for him. Corruption and cronyism were the major themes of the reformasi movement he launched in 1998. His movement captured both Malaysia and the world’s imagination—he twice appeared on the cover of TIME—when he gave up his role as Deputy Prime Minister and heir apparent to Mahathir to take to the streets. He paid for it with repeated incarcerations (1999-2004 and 2015-2018) and torture while jailed on trumped-up sodomy charges.

“I mean, in this country, the plundering was a mess and corruption is systemic. And if you stop that, it is a major success story. Not a single tender in the past nine months has been awarded through a negotiated process. There is [now] a proper tender, a transparent system. This is a major departure from the corrupt practices of the past. In Parliament, we have formed umpteen select committees. They can summon ministers and civil servants, question them. In the judiciary, there is not one case of appointments or decisions that I’ve interfered with,” he said.

2. China shows deference and steers away from disputed waters when Malaysia’s navy raises notes of concern or protest

The interview took place just a day after Anwar returned from China—his second visit to the country since assuming power last November. He was to fly out later that night to New York to attend the United Nations General Assembly. Malaysia’s relations with China and the U.S. naturally came up, especially its stance as the two major powers drift apart.

The China trip also came on the heels of the Malaysian government’s rejection of the latest edition of the “standard map of China” that lays claim to almost the entire South China Sea, including areas lying off the coast of Malaysia's Borneo region covering the states of Sabah and Sarawak.

Anwar said he publicly raised the matter at a gathering of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in the presence of Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and all ASEAN heads of state. “But to me, what is reassuring is the categorical statement by Li that they will honor and respect the claims of others,” he said.

“We do have issues [with China] like the South China Sea but the engagement has been working, in the sense that we have stated our position, and I’m at least reassured that China has said they will not do anything except through meaningful exchanges and dialogue. But of course, they are firm about the involvement of any third party in this dispute and conflict, and I share this sentiment,” Anwar added.

Anwar also said Chinese intentions of honest engagement are visible on the ground—or rather, in the water. “Thus far, when things are raised, or a polite note of concern is expressed, they do not necessarily withdraw but at least give some deference or consideration. Which means they do not, for example, aggressively enter our waters,” he said. “When we identify cases of them entering our waters, and give a note of protest, then they have steered away on a number of occasions.”

3. Huawei is proof that the U.S. can’t intimidate Malaysia

“The U.S. is a longtime ally and friend, and we continue to engage with them. But we cannot be intimidated in any way. A good example is our decision on 5G,” Anwar said.

“The previous administration, my predecessor, decided to have just one network system, [from Swedish firm] Ericsson. My position was to continue it because it is an important technology. But why shouldn’t we utilize the best of both worlds? So we chose [Chinese tech giant] Huawei to also participate," he added.

Soon after Anwar took power, he made it clear that he did not think the Ericsson deal was transparently agreed. His government began a review of the 11 billion ringgit ($2.5 billion) tender with Ericsson to build a state-owned 5G network. The review prompted U.S. and E.U. envoys to Malaysia to warn the government about risks to national security and foreign investment if it allowed in Huawei. These warnings clearly didn’t work. In May, Anwar’s government formally announced that the country will adopt a dual network model for its 5G rollout next year, rather than rely solely on Ericsson. “Of course, this displeased some people. But I can’t help it. My commitment and loyalty are to the people of Malaysia,” he told TIME.

4. Anwar thinks economic development and education are key to combating rising Malay-Islamist supremacy

When asked what his top priorities were for combating PAS’s rise, Anwar cited economic development first. “A more just, equitable system so that no community or part of the country is seen to be ignored or marginalized,” he said.

His slogan of “Malaysia Madani,” or “Civil Malaysia,” sums up his goals. The budget for this year focuses on low-income groups, including nearly $2 billion in cash handouts to the poorest 60% of the population. To generate the cash for such welfare measures, he is spurring investments with policy incentives including an ambitious $5.3 billion fund for renewable energy and green technology. He recently pulled off an investment coup of sorts by persuading Elon Musk to establish Tesla’s regional headquarters in Malaysia.

Anwar cited education second. “Because extremism, racism, religious bigotry breed easily among the more ignorant segment of the population. When I say ignorant, I don’t mean you’re not qualified, you don’t go to university. I mean the lack of understanding of the total message of a religion dependent on some of the mullahs and sheiks, with their very narrow, obscure interpretation,” he said.

Third, Anwar said that the government must do a better job emphasizing that Malaysia is a pluralistic society. “Although it is a predominately Muslim country, it is a multiracial country. And we have survived hundreds of years with the presence of Buddhists, Hindus, and Christians. And there is no reason why you should upset this and cause enmity.”

5. Anwar is open to PAS joining his unity government

PAS had been a long-time supporter of Anwar since his reformasi days and had allied with him politically in earlier elections. Co-opting PAS in his “unity government” would be a way of neutralizing the rising Islamist rhetoric in the country, and there has been speculation about the possibility. The only hurdle to a reconciliation is said to be a personality clash between him and PAS’s current leader, Abdul Hadi Awang, dating back to their student activism days when both of them were youth Islamist activists.

“The difference is nothing substantive, it’s just powerplay,” Anwar said, before adding that there is also a serious problem with the more hardline way PAS has started to interpret Islam.

“On whether we are prepared to engage with them, of course we do. We must. And I’ve sent [an invitation] to them ... Yes, I have been open to the idea from the beginning. After all, this is a unity government and we do what is best for our country. But of course, we are going to draw a line. Islam is the religion of the Federation, but this is a multireligious country and I want every single citizen in this country, of all religious persuasions, to know that they have a place in this country,” he said. “No one should be discriminated, marginalized, or ignored.”

Does that mean there’s no scope of reconciliation? Is PAS open to the idea?

“There has not been a clear rejection nor a positive response. The political climate is still a bit heated, so we’ll let it cool off for some time,” Anwar said. “Of course, contingent upon these major policy conditions being accepted.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com