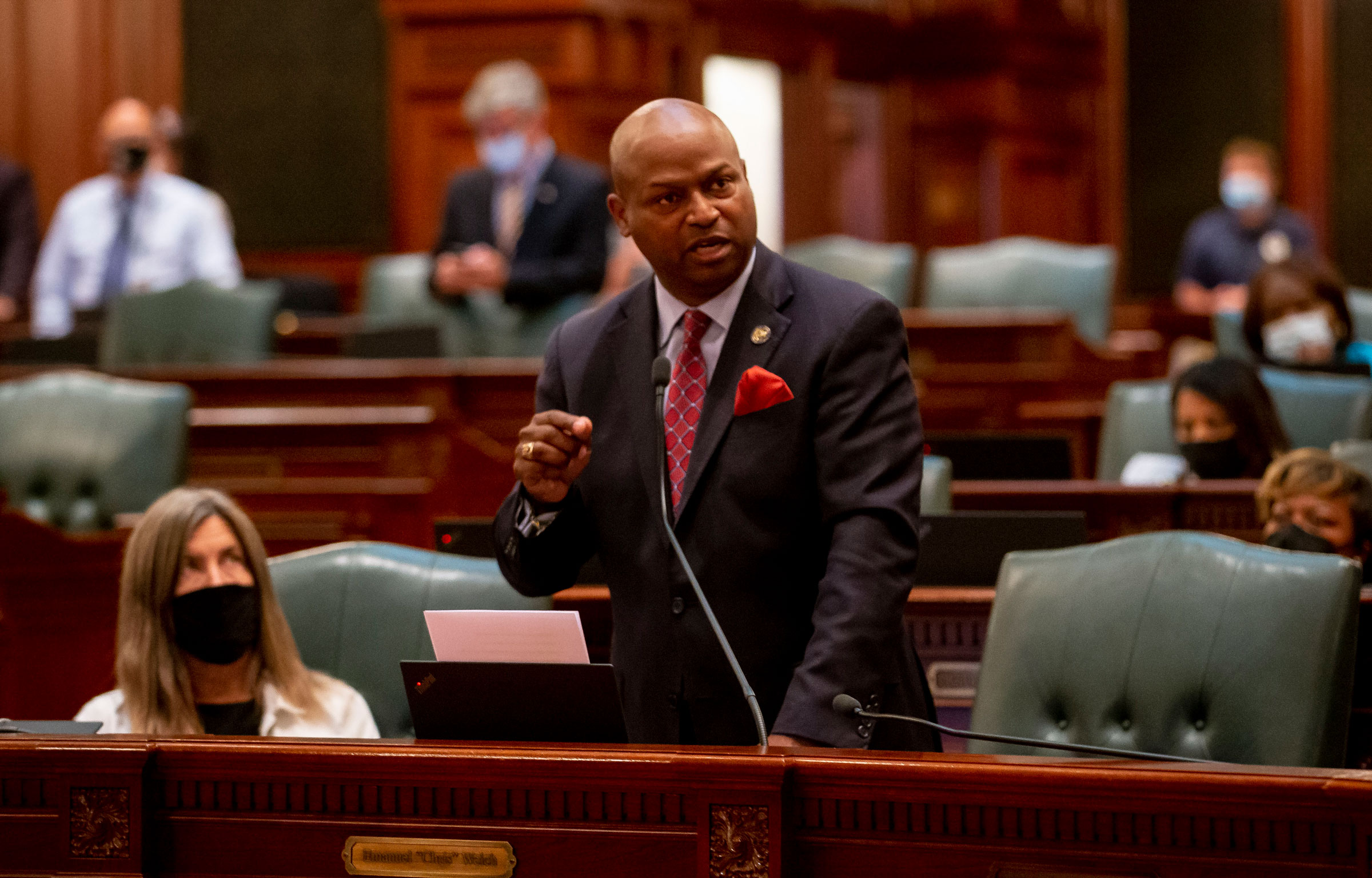

Illinois House Speaker Emanuel “Chris” Welch says he wants the state’s legislative staff to be allowed to unionize. The Democrat authored a bill he says would allow that last week, even though it’s unusual for the house speaker to write their own legislation. “I filed it in my name because I want folks to know that I’m 10,000% behind this effort,” he says.

The move took some of his employees by surprise. In the weeks leading up to the filing, more than 20 staffers in his office—who are part of the Illinois Legislative Staff Association (ILSA)—had said Welch would not engage with them around their effort to unionize despite his pro-labor rhetoric. Welch had not filled the employees in on his plans to file the bill, although he says his office had been speaking with them since November.

“We're not going to negotiate for anything crazy. We're not going to ask for million-dollar salaries," says Kelly Kupris, a policy analyst focused on K-12 education and a member of ILSA’s organizing committee. "We just want to be treated what we're worth, listened to, and know that we have a safe workplace that is able to put food on the table at the end of the day."

The push to allow legislative staffers to unionize is sweeping across different states, to mixed results. In California, the legislature recently approved a similar measure after at least five tries; it is now awaiting a potential signature from the governor. In New York, senate staffers launched a legislative workers group last year to attempt to unionize. Recent efforts to unionize in Washington, Massachusetts, Minnesota and New Hampshire have not succeeded so far. Oregon became the first state in the nation to allow legislative staff to unionize in 2021, although Maine allowed nonpartisan legislative employees that right in the late 1990s.

The effort in states follows success on the federal level, where congressional staffers succeeded in their attempts to protect staffers’ right to bargain collectively last year. Legislative workplaces are often characterized by a “big imbalance of power,” says Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, associate professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University, where he studies labor. “You have an elected official who has a pretty significant political role and often younger staffers, who are hoping to build a career in this area and may not have the bargaining power or ability to speak up or push back when working conditions are poor or deteriorating.”

Read More: Inside the Capitol Hill Staffers' Effort to Unionize Congress

The effort to unionize legislative offices takes place as a screenwriters strike helped secure a new contract, while actors remain on strike and so do United Auto Workers. Momentum behind labor is high amid the work stoppages. A 2023 Gallup poll found that 88% of Democrats, 69% of independents, and 47% of Republicans approve of unions. In total, 67% of Americans approve of them.

The energy around labor issues is also reflective of other attempts to unionize workplaces that have not traditionally had them, such as fast-food restaurants and graduate schools. “This year is different because there has been such a national focus on previously unorganized groups of workers forming and joining unions—as well as huge waves of strikes and labor mobilizations, which have put forth demands for better wages and working conditions,” says Kent Wong, director of the UCLA Labor Center.

Many view legislative staffers as the next natural target for unionizing. There’s often an expectation for legislative staffers to keep up with the blistering pace of an elected official’s schedule—“You’re going to be working crazy hours and not making a lot of money,” Wong says. Moreover, some staffers may be hesitant to form or join a union depending on the politics of their boss or their future political aspirations, he says. “We may never see a day when legislative staffers work 9 to 5 and have weekends off," Wong says. "However, we may see more accommodation."

A staff survey from ILSA, which collected signed cards from more than two-thirds of its coworkers to represent them, found that 84% have worked hours they were not ultimately paid for, either through pay or comp time. 84% say they struggle to pay bills or make ends meet, 37% currently have or have previously taken a second job or gig work to supplement their income, and 32% currently have or have previously taken out debt because the office income was not sufficient.

Although ILSA views Welch’s bill as a “good starting point,” according to Kupris, they continue to disagree with the speaker over the need for the legislation and the specific rules around organizing.

Last November, staffers approached Welch’s office about voluntarily recognizing them as a union. Welch did not believe current law allowed him to do so and encouraged them to go before the Labor Relations Board in Illinois, which said it did not have jurisdiction.

Welch's new bill will create a legal pathway for legislative employees in the House and Senate to organize, he says. (A few weeks ago, Welch’s mother asked him what was going on with his staff. “The law doesn’t allow it,” he says he told her of their wish to unionize. His mother asked: “Well, aren’t you in charge of making the laws?” He responded: “Well, on the house side, you’re right, Mom.”)

ILSA argues that they do not actually need a bill to unionize. “It definitely has good potential, but our right to organize is still existing right now and this bill…isn't granting our authorization to do that; we've had that right,” says Kupris. (They point to a Workers' Rights Amendment passed last year that establishes a constitutional right for employees to organize and bargain collectively. Welch argues that an existing law exempts staff in the General Assembly from organizing; ILSA disagrees.)

Kupris also says the effective date of 2026 is a “non-starter” for them; they have proposed 2024. "We just ripped that right out of the [California] bill," Welch says, adding that it is about taking time and "getting it right."

Experts suggest the recent passage of a bill in California to allow staffers to unionize starting in 2026 could inspire other states beyond Illinois to follow. California has often been a leader on labor issues, Wong notes: “If the California state legislative staffers are successful in unionizing, it'll send ripple waves across the country, and it will challenge other legislative staffers to think, 'Gee, you know, maybe it's not right that we work 24/7.'”

“We Democrats talk about equity and workplace safety all the time. In California, it was time to put our money where our mouth is,” says California State Rep. Tina McKinnor, a sponsor of the bill, who used to be a staffer in the statehouse. “As Democrats, we've asked all different types of businesses and organizations to unionize. I just think that before we ask any other business to unionize, we should make sure that we're protecting and unionizing our own employees in the legislature.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com