The U.S. child poverty rate more than doubled from 2021 to 2022. This was a policy choice. The U.S. Census Bureau found that child poverty rapidly dropped between 2020 and 2021 because of the American Rescue Plan’s Child Tax Credit—monthly checks sent directly to families making less than $150,000 per year with young children. Yet, Congress allowed the policy to lapse after only one year and child poverty reverted to its previous, very high level of over 12%.

U.S. lawmakers were not always indifferent to the vast number of U.S. children living in poverty. Head Start, the largest and most impactful piece of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty, aimed to address exactly this problem. And though underfunded since the 1970s, decades of research prove that Head Start has had meaningful and lasting impacts for the children and families that participate—including increased high school and college completion rates and increased “economic independence.”

The evidence from Head Start and from the Child Tax Credit point to an important lesson: child poverty can be addressed—if we take steps to reduce it through policy.

Read More: What's Behind the Spike in Child Poverty in the U.S.

Sargent Shriver, who directed the Office of Economic Opportunity in Johnson’s Administration, developed the idea for Head Start when he learned in the early 1960s that half of America’s poor were children. Looking for ways to counter political resistance to his antipoverty programs for adults, Shriver seized on the idea to transfer unused funds to a program that could give a “head start” to pre-school aged children. Shriver believed an antipoverty project for young children would be both effective policy and politics. Who could argue that a 4-year-old deserved to live in poverty?

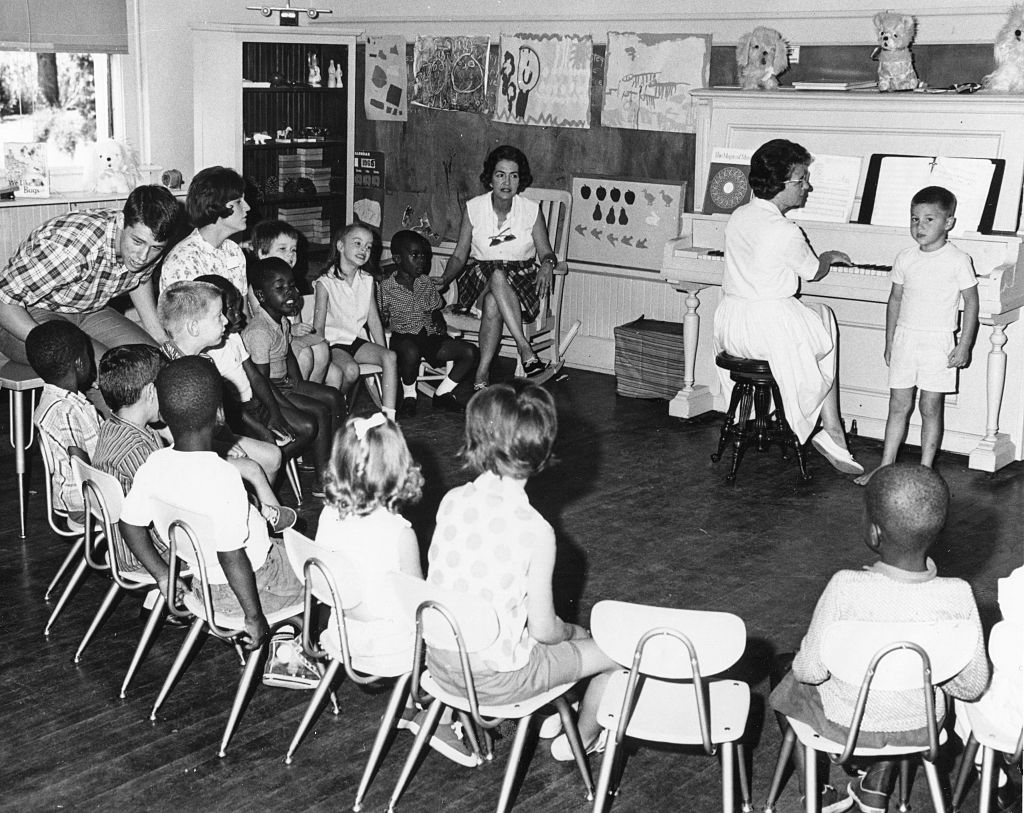

Shriver was right. Project Head Start gained broad bipartisan support when it began in the summer of 1965. A planning committee of experts proposed Head Start should be a comprehensive child development program. It would provide not only age-appropriate education, but also health, dental, social-emotional screenings, and nutritious meals. Critically, the committee also agreed that parent and community engagement was crucial to both the program’s and the children’s success.

Armed with a popular idea, Johnson and Shriver ignored the committee’s recommendations to roll out slowly with one or two pilot programs. Seasoned politicians, Johnson and Shriver knew to ride political momentum and get programs off the ground across the country quickly. Relying on the volunteer work of the First Lady, the wives of Congressmen and cabinet members, and federal agency interns, the Johnson administration was able to get Project Head Start operating in over 3,000 of the nation’s poorest communities in just 12 weeks, earning it the nickname “Project Rush-Rush.”

Shriver believed that community investment would increase the success of the programs and buffer Head Start from eventual political headwinds. Johnson Administration volunteers traveled to poor counties, reached out to the local leaders of community action organizations, and supported them through the federal grant application process. Civil rights leader Whitney White Jr. published op-eds in Black newspapers encouraging community leaders to support the program, claiming it would “rain a torrent of educational vitamins” on children living in poverty.

Within the first few years, Head Start programs were operating in nearly every congressional district in the country. Johnson expected that Head Start would soon provide two years of free comprehensive child development programs for every poor child in the nation. This was a radical notion in 1965, when 32 states did not even have public kindergarten.

In many ways the roll-out of Head Start was politically savvy, but in other ways it was limited by the biases of the privileged white people leading it. For example, the Johnson administration sought to link Head Start to improving children’s IQ scores, a now discredited measure of intelligence. It was a tactic that fed dominant narratives about the cultural deprivation of poor, especially Black, households. At the White House launch of the program, Lady Bird Johnson reinforced this narrative, saying that poor children were “lost in a grey world of…neglect” and that “some of them don’t even know their own names.”

Yet, the structure of the policy allowed federal dollars to bypass state and local governments and flow directly to community organizations to develop programs based on their own specific needs and assets, giving power and resources to those who had very little of either. Title II of the Economic Opportunity Act declared that its Community Action Programs, under which Head Start fell, required the “maximum feasible participation” of the poor. Bypassing state and local governments was particularly important in Southern states which were aggressively fighting federal desegregation and other civil rights mandates.

A key example was the Child Development Group of Mississippi (CDGM), the biggest Head Start grant during the program’s early years. Black women who had participated in Mississippi’s Freedom Summer in 1964 led the programs. They believed that “early childhood education was social revolution” for their communities.

For a time, it was. Head Start programs not only provided federal dollars to educate, feed, and provide medical and dental care to young Black children, they also offered better-paying jobs for working-class Black women outside the purview of white supervision. Without curriculum mandates, teachers developed culturally appropriate lessons that celebrated Black culture and history.

Read More: The Heavy Cost of Banning Books About Black Children

Mississippi’s white segregationists recognized the power of programs like the CDGM to uproot the social order. Local segregationists and Klansmen violently harassed CDGM workers—burning crosses in front of proposed CDGM sites, beating and shooting at teachers, and burning CDGM sites down. One of Mississippi’s U.S. Senators accused the group of mismanaging federal dollars and pressed Shriver to cut CDGM’s funding. He gave it to another local program. After a huge amount of public pressure on Shriver—including negotiations with Martin Luther King Jr.—he restored funding to CDGM, but at a much lower level.

The incoming Richard Nixon Administration endangered Head Start, and all War on Poverty programs. Though the Nixon Administration feared political backlash for cutting Head Start altogether, an early program evaluation gave them the excuse they needed to stop expanding the program. The 1969 Westinghouse Learning Corporation report stated that Head Start hadn’t, in its first four years, raised the IQ scores of participating children. Of course, the programs were designed to do much more and success could be measured in many ways—but the Johnson Administration’s emphasis on IQ had proven a major miscalculation.

Senator Walter Mondale knew that the report’s results contradicted the experiences of the people participating. “I have rarely talked to educators…or parents of children in Head [S]tart who weren’t delighted. They think it is working, they think it is helpful…Wherever you go you get the same reaction except from the reports like Westinghouse,” he stated.

Read More: What to Know About the Expiration of Federal Emergency Childcare Funding

Yet the Nixon administration refused to increase funding, and Head Start has remained underfunded ever since. Today, it only serves about 30% of eligible preschoolers and nine percent of eligible infants and toddlers.

Still, Head Start served over one million children below the federal poverty line in 2019 with comprehensive care—education, nutrition, health and wellness screenings, family supports, and opportunities for parent leadership. Economists have shown the lifelong positive impact the program has for generations of participants.

This example is instructive. Policymakers can meaningfully address child povertyif they choose to. History shows that providing resources directly to communities and families pays dividends for children.

Michelle Bezark, Ph.D. is a Senior Research Analyst at Start Early and a Visiting Research Scholar at Northwestern University. She researches and writes about the evolution of early care and education policy. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Michelle Bezark / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com