On October 1, 1993, a 12-year-old girl was kidnapped at knifepoint from her bedroom in Petaluma, California, during a sleepover with two friends, while her mother slept soundly in the room next door. This rarest of all kidnappings—a stranger abduction from the home—triggered one of the largest manhunts in FBI history.

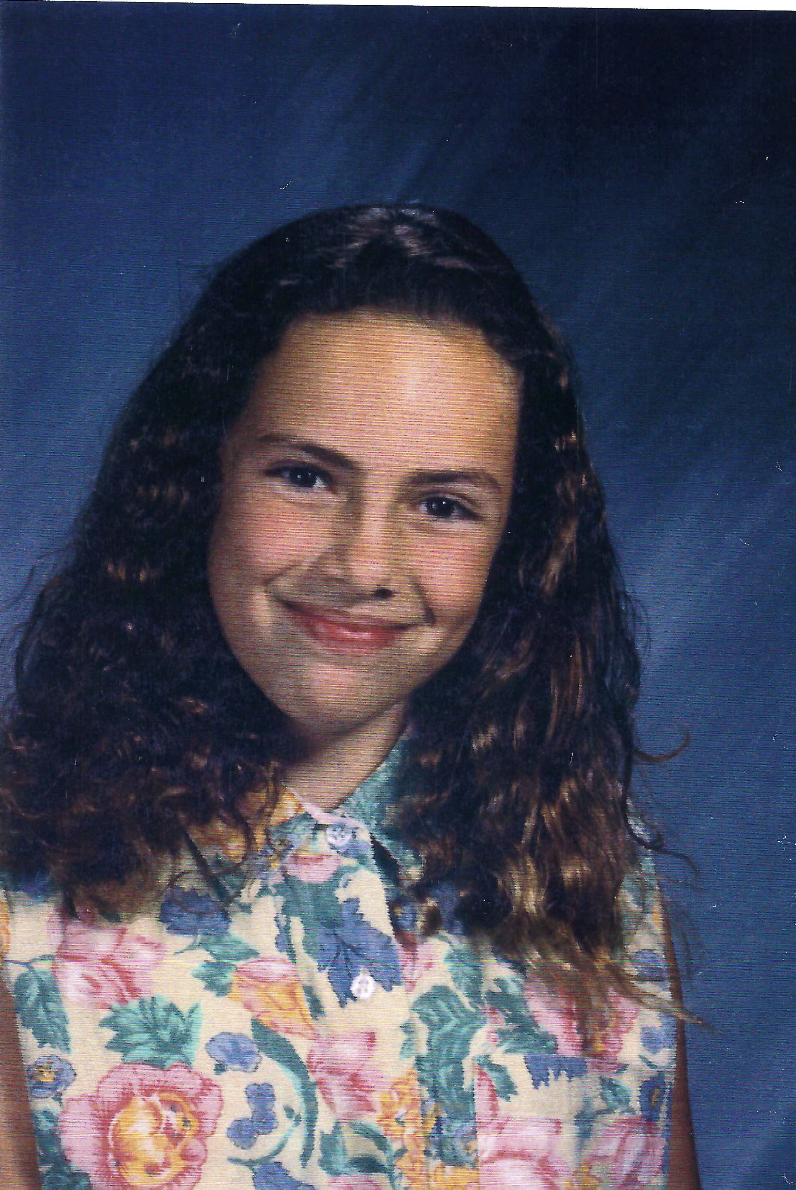

Her name—Polly Klaas—evokes the 1990s, a decade when America’s Most Wanted engaged the public to catch criminals and Soul Asylum’s “Runaway Train” video on MTV helped bring home missing kids. Americans of a certain age will remember Polly's dimpled face, which appeared on national news every night, on the cover of People magazine, and on more than 8 million flyers distributed as far as China.

The two-month manhunt unfolded at the dawn of the internet age, the first time a Missing Person flyer was posted online, not just stapled to telephone poles and Scotch-taped to storefront windows. This crime shocked the conscience of the nation and violated the sanctity of “home,” hastening the end of free-range childhood and the escalation of “stranger danger” culture.

After responding to 60,000 tips and investigating 12,000 leads, Petaluma Police and the FBI were still searching for a prime suspect. Then on November 27, 1993, Sonoma chef Dana Jaffe found “suspicious items” during a hike on her remote, wooded property off Pythian Road in Sonoma, California. Having watched the daily news coverage of the search for Polly Klaas, Jaffe instinctively saw a possible connection to Polly.

The crime scene

On November 28, 1993, flashbulbs popped and whined in the darkening woods off. Pythian Road, illuminating the falling rain. Forensic technicians Tony Maxwell and Frank Doyle, two members of the FBI’s first Evidence Response Team (ERT), were searching for trace evidence and photographing the soggy crime scene.

The black sweatshirt, red tights, and white ligatures that Jaffe had found while walking in the woods near her home had been gathered by Sonoma County Deputy Mike McManus that morning. To mark the spot where the evidence lay he’d left behind a condom and its wrapper, also found at the scene.

After photographing the dripping trees and the fallen leaves disturbed on the ground where the evidence had been lying, agents Maxwell and Doyle bagged and tagged the evidence for an overnight trip to the FBI lab in Washington, D.C.

At the FBI office in Santa Rosa, ERT member David Alford was packing for a red‐eye flight to hand‐deliver another batch of evidence—related to another suspect—to Chris Allen in the FBI lab. On his drive from Santa Rosa to the San Francisco airport, Alford swung by Pythian Road. Case agent Eddie Freyer and Sergeant Mike Meese gave him the latest evidence, still damp from the morning rain. It was placed in new luggage, secured with locks. Tony Maxwell packed up his camera gear, grabbed an over‐night bag, and joined Alford.

At the airport, they realized their luggage would exceed the carry‐on limit. They identified themselves as FBI and requested permission to place the bags of evidence in the seat between them to maintain chain of custody. But the flight was full, so that wasn’t possible. The airline crew allowed Alford to walk on the tarmac and personally load the evidence in the cargo hold of the plane—last bags in. He sealed the cargo door with crime scene tape. On the other end, he would unpeel the tape and carefully unload the bags of evidence.

The palm print

As the evidence began its 3,000-mile journey to Washington, D.C., Petaluma detective Andy Mazzanti drove to the Petaluma police station to begin “a full workup” on Richard Allen Davis, a parolee with an outstanding warrant for a recent DUI and a failure to check in with his parole officer. The FBI had officially named him a “subject” in the kidnapping of Polly Klaas.

Mazzanti worked the phones late into the night, calling every law enforcement agency listed on Richard Allen Davis’s rap sheet. He wanted everything in the files—booking sheets, mug shots, police reports, records of any and all contact.

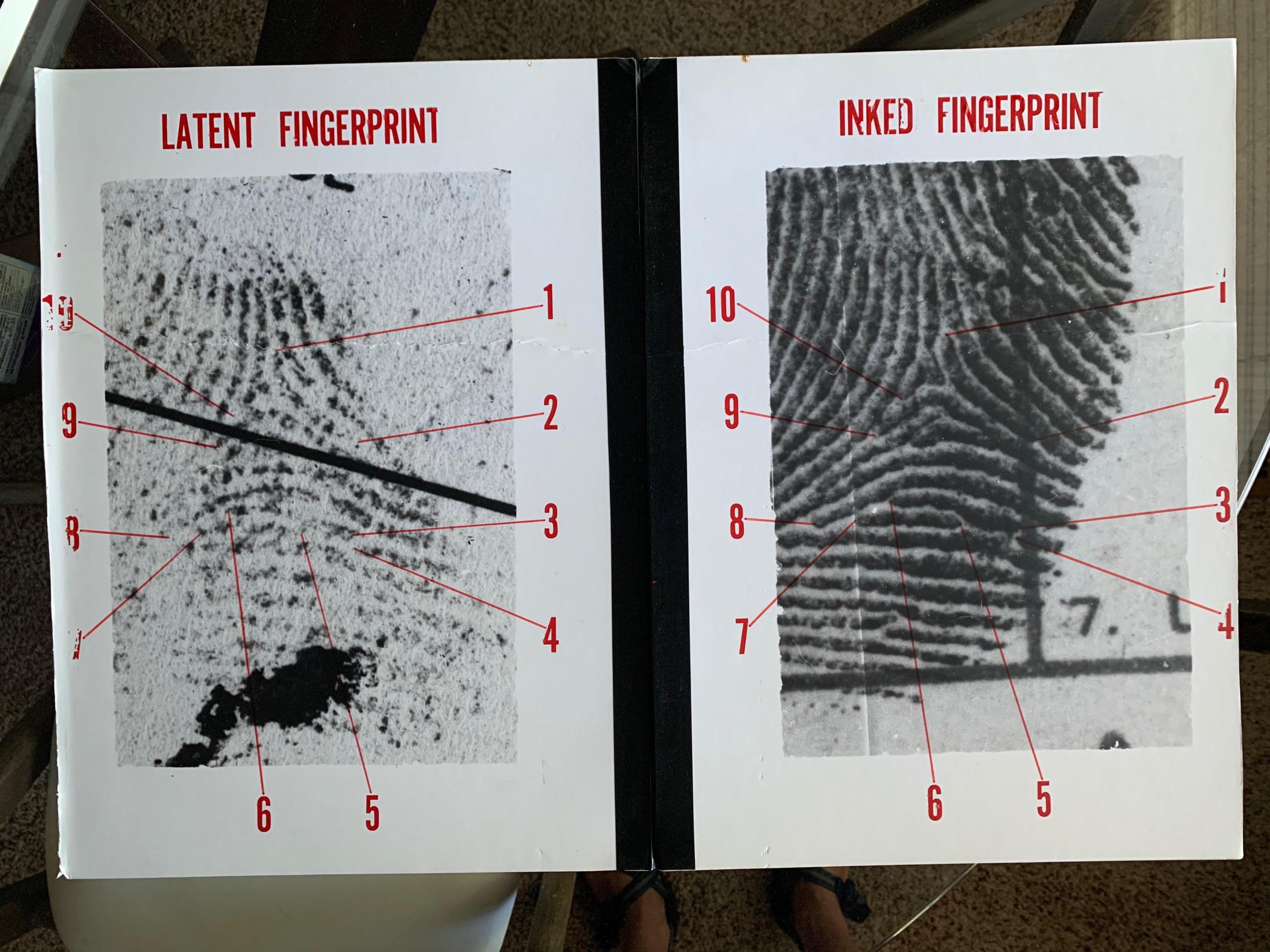

There was one particular item he needed more than anything: a palm print. The fingerprints found in Polly’s room after her disappearance were all accounted for. They had been matched with elimination prints taken from Polly’s family and friends, and therefore ruled out as related to the kidnapping.

All but one.

It was the palm print found on the upper rail of Polly’s wooden bunk bed—one of the forty‐eight latent prints that Tony Maxwell lifted in the dark with Redwop powder and the alternate light source (ALS)—technology so new at the time that the FBI didn’t even own it. He had borrowed a unit, tested it in his living room, and was using it for the first time in a major investigation.

Something about it had made Maxwell gasp and scribble the word “Bingo” next to entry A‐6 in the fingerprint log. David Alford had hand‐delivered it to the FBI lab on October 5. There it sat for two months, of little use without a suspect.

Now that they had a suspect, investigators needed his palm print. They already had a set of inked prints from Davis, but it didn’t include his palm. Authorities usually rolled only the fingers. Palm prints were less common, typically reserved for more serious felonies—bank robberies, kidnappings, violent crimes—at the discretion of investigators.

Mazzanti called the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Napa State Hospital, the California Highway Patrol, and a number of police departments that had booked Davis at some point. None of them had what he needed.

Around midnight, Mazzanti called the Stanislaus County Sheriff’s Office in Modesto, California, where Davis’s rap sheet noted he had been charged with robbery. That was back in the spring of 1985, when Davis and his twenty‐four‐year‐old girlfriend, Susan Edwards, had teamed up on a series of robberies.

As Mazzanti made those late‐night calls, he saw the opportunity to retrieve a palm print rapidly shrinking. He was working his way down the list of kidnappings, robberies, and assaults, yet not one of those case files contained what the FBI refers to as “major case prints”—a set with the palms, full fingers, and sides of each palm.

The offense that would ultimately yield the palm print was a broken taillight.

The crime spree

The 1985 Modesto robberies were the grand finale of a crime spree that consummated the three‐year romance of Davis and Edwards.

They had gotten together not long after Davis got out of prison in 1982 for kidnapping a woman named Frances Mays. Sue Edwards was 21 the mother of two young boys, and a wife in an unstable marriage.

One of their first joint ventures would eventually send him to jail: the kidnapping of Selina Varich, an acquaintance and the ex‐girlfriend of Edwards’s sister.

On the morning of November 30, 1984, Davis and Edwards forced their way into Varich’s Redwood City, California, apartment and threatened to kill her, along with her father and daughter, if she didn’t give them $6,000. When the terrified Varich tried to run away, Davis pulled her back inside and pistol‐whipped her in the head several times, gashing her scalp and splattering blood. They made her shower to wash the blood out of her hair, then drove her to the bank and forced her to withdraw the money. Varich, who needed five sutures to close her head wound, later described Davis as “evil, with scary eyes and gloating expressions.”

After escaping with the money, Davis and Edwards decided they had better get out of San Mateo, where Varich could identify them. Between December 1984 and 1985, they drifted from town to town in California, Oregon, and Washington, supporting themselves by selling drugs and stealing.

They might never have been caught had they not returned to Modesto. A week or two after their Modesto robberies in the first weeks of March 1985, it appeared they had gotten away with it all. Then on March 21, 1985, a cop noticed a defective taillight on their pickup truck and pulled them over.

The records check flagged outstanding warrants for their brutal attack on Selina Varich. Davis was arrested and booked in Stanislaus County, where deputies rolled inked fingerprints—including both of his palms.

Detective Andy Mazzanti didn’t know any of this as he searched for a palm print years later. He didn’t know he’d hit the jackpot when he called the Stanislaus County Sheriff’s Office to ask for records. It was late, and most folks had gone home for the night, so he left a message requesting files.

Mazzanti left the police department several hours after midnight and went home with a heavy heart. He had just learned that Poppy, his eighty‐ nine‐year‐old grandfather, had died of cancer.

Hours later, on the morning of Monday, November 29, 1993, 43 pages of records from Stanislaus County scrolled out of the fax machine in the Petaluma command center. They included a set of “major case prints”—ten fingers, both palms, and the blade of each hand. The prints were dated March 22, 1985—when Davis was stopped for his broken taillight. Detective Andy Mazzanti wasn’t there to grab the fax. He was out for two days on bereavement leave to attend Poppy’s funeral. He would not know—for twenty‐nine years—that he was the one who found the inked palm print.

A break in the case

The inked print was sent to the FBI Lab in Washington, D.C., where a fingerprint specialist confirmed it was identical to the latent print lifted from Polly’s bed frame. The development made national news.

The news caught the attention of a Bay Area resident named Marvin White, who hired ex‐convicts to help them transition from prison back into society. White saw Davis’s mug shot on TV and the wheels of his mind started turning. Could he help bring Polly home? He decided to pay Davis a visit.

On the morning of Saturday, December 1, White drove to Mendocino County Jail, where Davis was being held in isolation. In the visiting room, they spoke face‐to‐face for about half an hour. At some point, White leaned close, pointed an index finger at his open hand, and mouthed the words: “They found a palm print.”

Davis shrugged and nodded in acknowledgment but said nothing.

Later that day, Davis requested to speak with investigators. In a videotaped interview, Petaluma Detective Mike Meese offered him coffee and his favorite brand of cigarettes (Camels) then leaned in and asked the question that America was desperate to know.

“Is she alive?”

Cigarette poised, eyes glued to the table, Davis slowly shook his head. “She’s not alive.”

Sixty‐five days into the search, five minutes and forty‐four seconds into the interview, they finally had the answer. The answer nobody wanted. “Do you know where she is now?”

“Yeah.”

“Can you tell me?”

“I’ll show you,” Davis said.

This is an adapted excerpt from the book "In Light of All Darkness: Inside the Polly Klaas Kidnapping and the Search for America's Child."

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com