Before mining came to Chhattisgarh, a landlocked state in central India, Hasdeo Arand was a remote forest with a dozen tribal hamlets. Spanning more than 650 square miles, the forest is often called the “lungs of central India” and is home to endangered elephants, sloth bears, and leopards, as well as valuable water reserves. Many of the local villagers are Adivasis, or “original inhabitants” hailing from the Gond tribe, who cultivate crops in their backyards and sell woven grass baskets at the market. For them, this land is sacred.

This is how Umeshwar Singh Armo remembers growing up in Jampani, a small hamlet crowned with guava trees. This is where his ancestors were buried, and where he hopes future generations of his tribe will thrive. Today, the 43-year-old is the village chief of the local district of Paturiadand, home to around 900 villagers.

The area’s nearly 250 plant and bird species aren’t the forest’s only resources. Armo remembers when, as a schoolboy, he learned about another one: a shiny substance called “coal.” But it wasn’t until 2007 that surveyors sent by the state government began roaming the forest, using satellite cameras and laser scans to look for the stuff.

“We would all gather around to watch them survey the land. We were curious, even excited, about what it all meant,” Armo recalls. “But we could not imagine they would dig the ground out like this.”

More From TIME

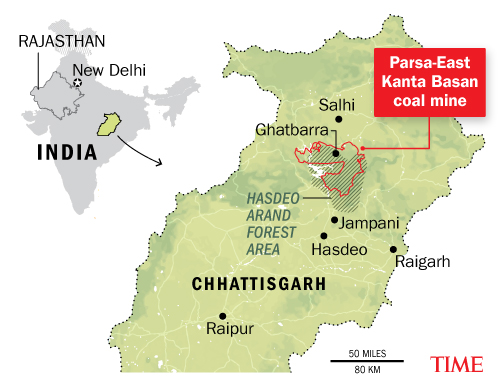

What the surveyors found was a miner’s jackpot: more than 5 billion tons of coal sitting under the pristine forest. In 2013, Chhattisgarh’s government marked out coal blocks, or designated areas for mining, and gave approval to Rajasthan, another state government, to extract the fuel. The Rajasthan government contracted the mining operations to Adani Power, India’s largest private operator and developer of coal mines and coal-fired power plants. Shortly after, a chunk of the forest roughly the size of five football fields was torn out to establish the Parsa-East Kanta Basan (PEKB) mine, named after two hamlets that once stood on the land. Today, what remains are large black craters.

Of course, the problems with coal don’t end with extraction. As a major consumer of it, India is also the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gasses (though its per capita emissions are around seven times lower than that of the U.S.). Most developed nations are winding down coal capacity to meet climate targets, but India and China continue to account for about 80% of all active coal projects. And while the U.S. and the E.U. have set goals of reaching net zero emissions by 2050, India says it will get there by 2070—another decade behind China’s goal of 2060.

In light of the most recent IPCC report’s stark findings, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres stressed that all countries need to move faster to reach those targets. India, which previously argued that phasing out coal would be too detrimental to its economy, may be succumbing to global pressure. In May, during a committee meeting as part of this year’s G-20 Summit, India’s secretary for coal, Amrit Lal Meena, announced that the country will close around 30 coal mines over the next three to four years.

Read more: How India Became the Most Important Country in the Climate Fight

But as the experience of Hasdeo’s residents shows, even efforts to prevent the damage coal does in the long term can have surprising—and damaging—effects in the short run.

Reuters reported that India also plans to stop building new coal-fired power plants—apart from those already in the pipeline. Not making any new commitments to coal is good news, says Tim Buckley, the director of the think thank Climate Energy Finance, but there’s a downside for those affected by existing operations: “'No new coal' means you rush to complete all the mines that are already there,” he said.

“If you’re a villager in that coal mine, you’re screwed,” he added.

Interviews conducted over three months in 2022 with more than 40 people—including locals who oppose the mine as well as those who support it; Adani workers at the PEKB mine; and teachers, police, and activists in the area—revealed how life in the forest has been transformed by the presence of a mining giant. For many, the transformation won’t end there.

“If we look far ahead, we all know that coal mining will only last 30 years,” Armo says. “But after that, our land will be destroyed. Then what? We have nowhere else to go.”

When coal is extracted from PEKB, its journey has just begun. The fuel itself travels north by rail and truck to Rajasthan, while the rewards of selling it are reaped by Chattisgarh’s state capital of Raipur. There, the dizzying development of towers, malls, and hotels stands in stark contrast to life for the Adivasi forest dwellers who work the mines, 90% of whom depend on agriculture and forest produce for their livelihoods.

It’s a pattern repeated across India, the world’s second-biggest importer, consumer, and producer of coal. By next year, amid growing demand for electricity, its government plans to have extracted over a billion tons just since 2022.

The Adani Group is key to these ambitions. Founded in 1988 as a commodity trading business by Gautam Adani, now India’s second-richest billionaire, it has become one of the country’s largest conglomerates, operating ports, airports, and thermal power production plants. Currently, the group also has government contracts to produce and sell more than 29 million tons of coal in India every year, claiming 50% of the country’s market share in coal trading. In June 2022, when the government issued 22 million tons’ worth of coal import orders to overcome domestic shortages, 19 million went to Adani.

Adani is no stranger to controversy. In 2010, the company announced that, to meet India’s rising energy needs, it would develop a new mine in the Galilee Basin in Australia. The backlash was so massive that Adani struggled to finance and insure the mine; he eventually self-funded it with $2 billion from other Adani entities. By last November, it had produced 18 million tons of coal, less than a third of its capacity. During an interview with The Financial Times last year, Adani hinted the mine might have been a mistake. And earlier this year, a damning report published by Hindenburg, a U.S. short-selling firm, accused the Adani Group of “pulling the largest con in corporate history” through stock manipulation, accounting fraud, and other malfeasance. The Adani Group issued a 413-page reply calling the allegations “stale, baseless, and discredited,” but the report nevertheless amplified the scrutiny around Adani mining operations, which experts say contributed to the company’s decision in February to halt an $847 million acquisition of another coal-fired power plant.

Yet the appeal of the coal business is clear. After Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP party came into power in 2014, it introduced a new law to enable what’s known as the Mine Developer and Operator (MDO) model, a process that allows government-owned coal blocks to be contracted out to private companies that take responsibility for land acquisition; resettlement and rehabilitation; and mine operation—all at undisclosed rates under confidential agreements. The Adani Group is India’s biggest coal MDO. An Adani spokesperson told TIME that all of its nine MDO contracts were acquired through “a highly competitive and transparent bidding process with a number of contenders.”

Critics say Adani’s dominance is thanks in part to his close ties with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. And the BJP isn’t the only political party that has boosted Adani’s coal empire. In 2015, Rahul Gandhi, then the leader of India’s main opposition party, Congress, made assurances to villagers in Chattisgarh that their land would not be given away for mining. After Congress was voted into power in the state in 2018, however, it contracted the Adani Group to operate coal blocks in the Korba district the following year. Four villages—including Madanpur, which Gandhi visited to make those promises—face the threat of displacement if mining continues.

Read more: The Climate Rifts Biden and Modi Couldn't Heal

The Adani spokesperson emphasized to TIME that, under the MDO process, the company is simply a government contractor. In PEKB’s case, the spokesperson said, this meant the state of Rajasthan was responsible for any concerns raised by villagers. But Adani Group owns 74% of the shares in RRUVNL, the government company that issues the contract—meaning Adani Group itself is the majority stakeholder over PEKB’s coal.

It’s not that coal faces no resistance in India: In fact, PEKB is one of the country’s most controversial land-rights cases ever. The mine is vehemently opposed by those who see it as the force behind the destruction of their land, homes, and livelihoods. In 2010, India’s coal and environment ministries conducted a joint study that found the forest should be a “no-go area” for coal mining because of its rich biodiversity.

The government approved the mine’s construction a year later anyway.

PEKB workers take their breaks sitting at the edge of the mine, where they gaze at the split between the open-cast pit and what remains of the Hasdeo forest.

The area’s tribal villagers know what mining can do. “Right now, our livelihoods are flourishing because of the forest,” said Mudhram Markam, a 41-year-old from the nearby Tara village who has been involved in the local resistance efforts since 2015. “But tomorrow when they dig out our land for coal, we will get sick and have trouble breathing, our water reserves will dry up, and things will just get more difficult. And most of all, the forest will be destroyed.”

In many ways, Adani’s promise of progress in exchange for coal is a familiar one. In America’s Gilded Age, mining giants powered the nation—and even today, U.S. coal companies are struggling to meet their cleanup obligations for the waste and pollution created by more than 50,000 mine openings as communities grapple with the legacies of the industry.

Read more: Below the Surface: Photographing Coal Miners Without the Stereotypes

That waste is only just beginning to accumulate in Hasdeo, but in Adani’s official telling of the PEKB story, that trade-off was worthwhile. The company, which also told TIME it was dedicated to being part of India’s commitment on climate change, said it has created over 15,000 jobs and built a colony of homes and toilet facilities in a neighboring village. It added that, through its corporate social responsibility wing, the Adani Foundation, it has been “continuously working” towards improving the quality of life in and around the peripheral villages of PEKB.

Most notably, the foundation set up the Adani Vidya Mandir, a school that offers free education in English for 800 students. For local Adivasi families who belong to the lowest rungs of India’s oppressive caste system, the school offered children a gateway to opportunity. But many parents who enrolled their children say the quality of education has worsened since the school first opened in 2013. One villager who teaches at a neighboring public school said that almost half his class last year came to him as new students after they unenrolled from Adani’s school.

Meanwhile, the mines are already taking a toll on the health of those working in and living near them. “Every step in the generation of electricity by coalfired thermal power plants…[carries] serious risks on the health of miners, plant workers and residents in the vicinity of mines and power plant,” stated a 2017 study from New York University, which looked at the health and environmental impact of mining in Chattisgarh. A 2020 study by the Indian Council of Medical Research found that the tribal population in villages near the city of Raigarh, who live in a similar set-up to the villages of Hasdeo, saw increased health risks like acute respiratory infections and tuberculosis, as well as increased exposure to man-made harms such as road accidents after the coal mine opened.

Several PEKB workers who spoke with TIME expressed frustration that when land collectors convinced them to sell their homes and work for the mine, they were promised around 12,000 rupees ($144) a month. Instead, they say, they earn less than half that sum, well below the recommended average income from trade unions in India. And while the Forest Rights Act of 2006 requires that all tribal villagers must give permission for commercial use of their land, multiple people who spoke to TIME allege that, when tribal leaders held meetings to gather their consent, villagers’ signatures were either forged or taken after they were given bribes by land collectors working for Adani.

The Adani Group has denied the allegation of deceiving council members, and fiercely contests what many villagers told TIME. While the company did not comment specifically on the salary discrepancy or educational outcomes at its school, in a statement to TIME the group said compensation was determined after “a detailed consultation process with the local community.” It added that “responsible mining practices” made PEKB “a model mine that’s frequently visited by representatives of other energy companies and academic institutions.”

Some villagers do support the Adani Group’s operations. Those who sold their land did so because they saw it as an opportunity to access not only previously unimaginable sums of money but also upward mobility through a job for the Adani corporation.

Those promises haven’t always panned out. One Adivasi mine worker, whose name has been withheld to protect his job, resides in the village of Salhi and has been with the PEKB mine since 2013. Six days a week, he works eight-hour shifts counting blocks of coal. He, like a dozen other mine workers who also spoke with TIME, says the working conditions are dismal. “We are not happy here, but we need to keep working out of necessity,” he said.

Those who accepted the Adani Group’s offers feel they have nowhere else to go: “We were screwed on both ends: by the collectors who came to take our land, and by Adani, who promised us progress,” said the mine worker from Salhi.

“Adani is making a fool out of us,” said another.

In March, India’s Supreme Court was asked to weigh in on the future of PEKB after three different pleas were filed in relation to the mining operations: An advocacy group formed by Hasdeo’s villagers and an environmental lawyer both challenged the operations on the grounds, respectively, that they displaced local villagers and harmed the environment, while Rajasthan’s state electricity board asked the court to approve the mining to meet its electricity needs.

The apex court—which often takes years to deliver final judgments amid a backlog of nearly 70,000 appeals and petitions—is yet to hand down a final judgment on the matter. This spring, despite the opposition of the state government, the federal government announced a new round of auctions over the unoccupied coal blocks in the forest.

These questions are part of the global puzzle that climate experts call “just transition”: the idea that shifting away from fossil fuels must be done responsibly, taking into account the needs of local communities. Just as the negative impacts of mining are often borne by marginalized people, so too are the negative impacts of achieving a sustainable future—necessary though that is. “Change is in the air: renewables are already out-competing coal, and India’s central and state governments are under increasing pressure to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions,” writes Sandeep Pai, an expert in India’s energy transitions. But, he continues, “Developing a long-term just transition strategy for the coal sector in India will be a major undertaking.”

Read more: How One Activist Stopped Ghana From Building Its First Coal Power Plant

So while the future of PEKB is hung at the Supreme Court, residents weigh their own futures too.

Last September, Umeshwar Singh Armo, the village chief, was awakened by someone knocking on his door at 4:00 in the morning. He unlatched the bolt of his thatched hut and peered outside, spotting two men in police uniforms. They asked him to accompany them to the local police station, where a senior official wanted to speak with him. “It won’t take too long,” he recalls their reassuring him. “We’ll drop you right back.”

Though alarmed, Armo had come to expect these situations. He had helped form the Hasdeo Arand Bachao Sangharsh Samiti, or the Save Hasdeo Forest Committee, which has been protesting the mine for a decade. The community’s efforts have become a force of resistance against the authorities, with marginal success as successive governments, both local and federal, stop and restart mining in the area.

Armo, who is tall and soft-spoken, described these events when he met with TIME last October at the committee’s local office. He arrived on his bicycle with a Gond tribal scarf draped around his chalk-colored shirt and quietly removed his shoes before sitting on a jute charpai, or a woven bed.

The police arrived shortly after rumors began circulating among villagers that the forest department was planning to cut more trees to clear land for a second phase of mining in the neighboring villages of Pendramar and Ghatbarra. Armo suspected the police were trying to discourage him from protesting, but he cooperated with their request. That day, they detained him, along with other members of the committee, for over 12 hours, he says.

While he was in custody, officials erected barricades to prevent villagers from passing through areas designated for clearing, while nearly 2,000 trees were felled to clear 1,138 hectares of forest.

Armo realized that he had been deceived when he was given no clear explanation about what was going on at the station. (Police told TIME Armo and others were detained “for their safety.”) Enraged, he asked the officers to write in their records, When Hasdeo was being destroyed, we were busy tricking the villagers who tried to save the trees, so that “future generations would read this and tell you how wrong you were.”

Now, Hasdeo is a surveillance zone, with young men recruited by the Adani group keeping an eye on the protesters and the police patrolling the area to ensure the mining operations continue. Villagers fear retaliation for speaking out. But Armo is undeterred. Every sunset, he gathers under a large tarpaulin tent to talk to other villagers about the latest developments in the mine and to plan future resistance efforts. For him, the fight to save Hasdeo is also a larger fight for the Adivasi existence.

“We stand to lose so much if we don’t fight: the land, the river, the animals and plants, the sanctuaries, the livelihoods,” he says. “We are fighting for all of it.”

—Reporting for this story was supported by the Matthew Power Literary Reporting Award from N.Y.U.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Astha Rajvanshi / Chhattisgarh, India at astha.rajvanshi@time.com