This year, during the heat of summer, when temperatures in New York surpassed 90°F, the 22 solar panels on the roof of my house were doing absolutely nothing.

This is not something I learned until September, four months after my husband and I bought this house with a purportedly functional leased solar system in upstate New York, months after logging into a website that inaccurately told us that the panels were working, months after we forked over $6,000 to prepay the remainder of the 20-year lease to the company supposed to be maintaining the solar panels, Spruce Power, which happens to be the largest privately held owner and operator of residential solar in America.

A third-party technician dispatched to our house by Spruce in September blamed squirrels that chewed on some important wires. Spruce blamed the previous owners, who they said fell behind on lease payments; in September, Spruce told us it had disconnected the system previously but that did not explain why they’d taken our money to prepay the lease on the panels in June. The panels are still not working to full capacity. (Made aware that this article was in the works, Spruce said in September that it will repay us for the months the panels were not working.)

We are not alone. Obscured by the recent rush to sign up households for rooftop solar and speed up the electrification of America are those who already have solar panels on their roof that do not work. Many were early adopters who did the “right” thing for the planet, installing solar before the expanded financial incentives that came out of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Because solar was more expensive in the 2010s, many entered into leases with solar companies to defray upfront costs, and many were left in the lurch when those companies went out of business. Often, their solar leases were packaged and sold, alongside thousands of others, to private equity companies and other investors who were not incentivized to ensure, years into the leases, that service was good or that panels even worked.

Read more: How The Inflation Reduction Act Will Spur a New Climate Tech Ecosystem

“Bad operators have left many people with broken systems and a bitter taste in their mouth,” says Daniel Liu, head of asset commercial performance at Wood Mackenzie, an energy research firm. “It costs a lot to actually service these panels, and a lot of people have fallen through the cracks.”

There were 5,331 complaints containing the words “solar panels” submitted on reportfraud.ftc.gov between Jan. 1 and Sept. 19 of 2023, up 31% from the entire year of 2022 and up 746% since 2018, the first year for which the Federal Trade Commission has data, according to the FTC’s response to a Freedom of Information Act filed by TIME.

These cases are important to consider amidst the growing interest in rooftop solar, prompted by big incentives in the IRA and volatile energy prices that are leading people to want to have more control over the cost of their own power. Around 4 million U.S. homes now have rooftop solar, up from 300,000 a decade ago, according to Eric O’Shaughnessy, a clean energy consultant.

But in terms of regulation of the companies providing those solar panels, not much has changed since ours were installed in 2014. The thousands of households signing up for solar today hoping for energy independence could also find themselves dependent on opaque companies who are slow to respond to problems or who are no longer in business. For all the promise of solar—that it can help wean us off fossil fuels and cut our energy bills—the focus on speeding adoption has come at a cost: it allows unreliable players to flourish in a booming industry.

“The issue is regulation—there’s none of it, and customers like us are just sitting ducks,” says Steve Drapeau, who lives in Walnut Creek, Calif., and says his solar system has not worked since August 2022. He’s an active member of a Facebook group for customers of Spruce Power whose systems do not work as promised, and says he tries to get the company to pay attention to his case almost every single day.

Spruce is not the only company with unhappy customers, although it seems more hated than most; it gets an “F” from the Better Business Bureau and receives an average rating of 1 out of 5 stars from customers on the BBB’s website. Sunnova, a competitor, also receives an “F,” though it gets 2.61 stars out of 5 on the BBB’s website. A third competitor, SunRun, receives an A+ but the BBB makes a note on its page that “based on BBB files this company has a pattern of complaints.”

Companies that sell, rather than lease, solar panels are unpopular, too; dozens of customers have filed complaints against a company called Pink Energy, which abruptly went out of business in September 2022 and filed for bankruptcy after allegedly selling defunct solar panels and misleading customers about their benefits. Even some of the biggest solar-power companies in the U.S., including SunRun, Tesla, and SunPower have faced legal complaints about the sales practices, solar panels, and financing options at their companies or companies they’ve acquired.

“I get so many calls about solar I could never take every case—I would be working forever,” says Kevin Kneupper, a lawyer who represents consumers in cases against solar panel companies. “You could occupy every state attorney general, full-time, just doing solar.” (Kneupper says that when people ask him if they should get solar panels, he no longer can say yes in good conscience because of what he’s seen.)

The attorneys general in many states have sued companies that they say targeted vulnerable populations and misrepresented the benefits of rooftop solar. But the attorneys general appear focused on emerging companies trying to sell new solar systems door-to-door rather than those ostensibly servicing systems already in place. Their lawsuits do not tackle a bigger, more intractable problem: there are companies whose job it is to maintain or guarantee solar systems that are already on customers’ homes, and their track record is decidedly mixed. As William Tong, the attorney general of Connecticut, told me, “if you’ve been deceived, we will help you, but at that point, the damage is already done.”

Indeed, it’s not something that the solar industry likes to talk about—in a time of extreme climate change, advocates are so hellbent on expanding rooftop solar that they are loath to criticize the industry’s bad actors, worrying that it may slow broader adoption. No one wants to get in the way of a good idea, even if that good idea can go very wrong.

The problem with residential solar leases

The solar system on my rooftop is leased; the house’s previous owners signed a 20-year contract in 2014 with a now-defunct Minnesota company called Kilowatt Systems. It is not rare for a solar company to go out of business and for its leases to be acquired by another firm; around 8,700 different companies installed at least one residential solar system between 2000 and 2016, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Many of these installers were contractors who only dabbled in solar, but still, only 2,900 of those companies were still active by 2016.

We did not think the panels were a very good deal when we bought the house, but couldn’t find anyone who could confirm this; our real estate agent had never sold a house with leased panels before and our lawyer said she didn’t review solar contracts. Under the lease the previous owners had signed, which we were expected to take over, payments had started out at $67.92 a month but rose each year, reaching $116.93 in 2034; meanwhile, the amount of energy guaranteed each year lessened as the panels aged.

Still, the panels cost a tiny fraction of what the house did, so when the previous owners agreed to split the cost of paying off the rest of the lease with us, we figured we’d gotten a good deal. We each spent around $6,000 to prepay the remainder of the lease, deciding not to buy the panels outright because we wanted the benefit of maintenance and support from Spruce Power.

Leasing is still an option for people who want solar panels on their roof, but it was even more popular in the early days of solar a decade ago. Only about one-third of residential solar systems installed in 2014 were owned by the customer, compared to two-thirds today, according to data from Wood Mackenzie.

The leasing model helped rooftop solar flourish in the 2010s, eliminating at least one barrier to adoption: high upfront costs for homeowners. Companies got the money to finance these costly installations from packaging and selling tens of thousands of solar leases to private equity and institutional investors.

More From TIME

But it’s much easier to sell solar systems than it is to install them on thousands of homes and maintain them, and cash flow became a problem for many companies who were trying to gain market share as quickly as possible. As early businesses ran out of money and went kaput, solar lease portfolios were sold from one company to the next, sometimes acquired in bankruptcy proceedings for pennies on the dollar. “These companies went out of business, bankers bought the portfolio and are still collecting fees, but they’re not set up to provide support,” says Vikram Aggarwal, the CEO of EnergySage, a solar services marketplace. He estimates that over half of all solar installations have been orphaned, meaning that the company that originally installed the panels or pledged to maintain them has gone out of business.

It’s not surprising that companies struggled to keep up with necessary maintenance and repair for solar panels on peoples’ homes; it costs much more, on a per watt basis, to maintain rooftop solar than utility-scale solar, says Liu, the Wood Mackenzie analyst. Utility-scale solar provides such relatively large amounts of power that they have the cost of regular inspections and maintenance built in, while residential rooftop solar is often installed and then largely forgotten. Even so, one recent study found that utility-scale solar projects degraded at a higher rate than analysts had predicted, meaning they produced less solar than anticipated.

The same is likely happening on rooftops, especially since homeowners can’t see what’s happening on their roof or if there are squirrels gnawing on their wires. What’s more, it’s expensive to send a truck to repair rooftop solar panels because electricians have been in high demand and because a company’s clients may be spread out across a metropolitan area, requiring technicians to spend a lot of time in transit.

Read more: The Overlooked Solar Power Potential of America's Parking Lots

The stories I’ve heard of “efforts” to repair solar systems are almost comical. Spruce Power, for instance, contracts with a company called NovaSource to service panels. But one Spruce Power customer, Joel Zuckerman, who initially leased a solar system for his Maryland home with a now-bankrupt company called Sungevity, says that it took NovaSource months after his panels stopped working to send a technician to his house, and when they did arrive in March 2022, they didn’t even go on the roof to check out the system. They came back in July, he says, but without the equipment they needed to fix the panels. It took over a year before technicians arrived, in September 2023, with the right equipment, he says—but still were unable to fix the system. “I realize I am just screaming into the void at this point,” Zuckerman says. (NovaSource did not return a request for comment. Spruce said it was not familiar with the case but that “in certain markets, it takes NovaSource a while to respond.")

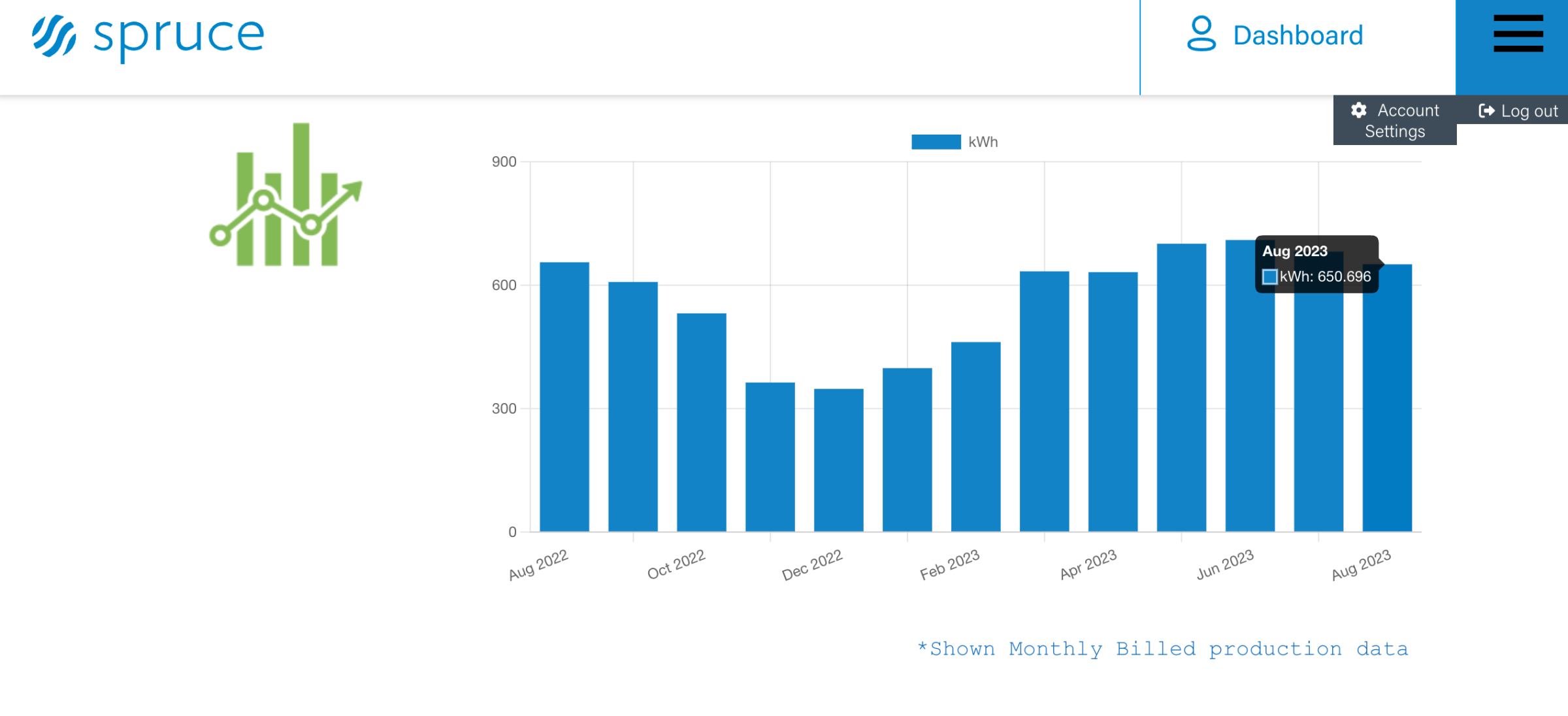

When we bought our house with Spruce panels on the roof, the closing was delayed for weeks because its customer service took that long to transfer the solar agreement from the sellers’ name to ours. When we called Spruce before the sale to make sure the system was working, a customer service representative told us to log into the company’s portal, where we could see how much the panels were producing. It showed that in March, the system produced just over 600 kilowatt hours (kwh) of power, with production increasing to about 680 kwh per month in July. An asterisk at the bottom said “shown monthly billed production data,” and though we later learned that this amount was just an estimate, nowhere did the page make that clear.

After getting a surprisingly high energy bill in August, a month after we moved in, I emailed Spruce’s customer service to check if the panels were working. I never got a response. When I called customer service later that month, a representative told me that the system had been disconnected since at least January because the previous owners hadn’t paid the bills. It was not until the end of August when I emailed Spruce Power saying I was a reporter that the company said it would send a technician; at that point, we also learned that Spruce does not do any of its own maintenance but hires another company to do it. The technician came in early September, looked at our system, fixed some of the panels but said he would have to come back another time to fix the rest. Spruce has not yet sent anyone back, even though I got a personal note from Jon Norling, the company’s chief legal officer, apologizing for the problems.

Norling says that until September 2022, Spruce was owned by private equity, which did not see the need to invest in customer service. Since being acquired by XL Fleet, a distributed solar energy provider, the company has invested significantly in improving the customer experience, he says. It launched “Spruce University” earlier this year in an effort to improve customer service, and wait times appear to have shrunk from nearly an hour earlier this year to just a few minutes now. Spruce’s leases are designed to be a 10% savings over the local utility rate, he says, and if the customer can show that they’re not saving money, Spruce will modify the lease rate. Norling apologized for my experience, adding that only about 40-50 customers of the roughly 72,000 rooftop solar systems across 13 states owned or administered by the company—or less than one tenth of a percent—have issues like mine.

Norling also had an explanation for why Spruce told me that our panels were working when they in fact weren’t: 3G technology. Older residential solar systems were installed with meters that communicated over 3G, he says, and when cell phone service providers discontinued 3G, those meters were forced offline. Spruce is upgrading the meters to 4G, but the chip shortage has led to slow production of new meters. Until they’re all fixed, what I and other customers saw on Spruce’s portal were estimates, and not the actual amount of solar we were getting. (The company never made that clear, and Norling apologized that the company did not specify that those calculations were estimates.) Spruce has offered to reimburse me for the months I did not receive solar power, but I also recently received an email from customer service, to whom I had sent my energy bills, saying they “were not able to review them to completion,” which is a sentence that may or may not have been written by an actual human.

The technician who came in September helped me log in to a system run by Enphase, the company that made the inverter, or brains, of the panels, and it showed that the panels had been offline since January 2019. Spruce says the previous owners were delinquent on their bills since 2019 and that it had sent them numerous notices about their system; the previous owners say they never received any notices from the company and that they were paying their solar bills until they sold the house in June 2023.

I should say here that my experience is by no means typical of everyone who gets solar installed on their roof. Sunnova, another company with poor BBB ratings, told me, for instance, that they upgraded all of their 3G meters before the 3G transition so that no meters went offline; Sunnova also has a global command center in Houston that allows the company to monitor every system in real-time and troubleshoot problems. It expanded its service technician team by 230% since 2020.

A neighbor of mine, Thomas Wright, installed solar panels on his home a year ago from SunCommon and has only positive things to say; he expects to have earned his money back in seven years and for the remaining 18 years that the panels are guaranteed, he’ll be generating electricity for free.

New York’s Solar Energy Industries Association (NYSEIA) would like me to tell you that the annual cost of solar is almost always cheaper than the price customers pay to the utility for power, and that solar panels increase a home’s value. States like New York use tax rebates to incentivize consumers to choose reputable contractors to install their panels, and modern technology enables homeowners to monitor their panels’ production hourly so they know if something is not working, says Noah Ginsburg, the executive director of NYSEIA.

There is a need, he says, for more real estate brokers and lawyers to be educated about solar leases and rooftop solar so they can better serve their clients. “We could do a better job proactively doing outreach to brokers and educating them, but they should be educating themselves as well,” he says. “This is going to be the rule, rather than the exception: rooftops in the United States are gonna have solar over the next decade.”

Solar customers can lose their right to sue

You might think there is a simple way out of these solar leasing nightmares: stop paying the company until it fixes your solar panels, or hire a lawyer to get your money back. But most solar leases have a clause in them requiring any disputes to be resolved by arbitration, which has been found to restrict the amount of relief consumers can receive.

Brad Cummings, who lives in Long Beach, Calif., says that subsidiaries of Spruce Power have been sending him collection notices and charging him late fees for more than three years even though the solar system he originally leased from a company called Tredegar Solar Fund I LLC has not been operating at full capacity since 2019. Tredegar “has simply been making up the numbers it bills,” he alleged, in a demand for arbitration he filed in 2021; he also says that Enphase, the company that owns his inverter, told him that his system had not reported data since November 2019, but Tredegar continued to send him bills that included specific amounts of power generated. During this time, he says, Tredegar hired Spruce to service his account.

The arbitrator ruled in January 2023 that Tredegar had materially breached the billing and payment provisions of its contract and owed Cummings $2,225 —much less than Cummings had requested. Despite that ruling, Cummings is continuing to get invoices from Spruce, which claims he owes $5,239.63 and is also charging him late fees for not paying those invoices. In July 2023, they sent him a letter warning him that failing to pay “could have significant negative impacts on your overall credit profile.”

The ruling that Tredegar breached part of its contract should mean that Cummings has no obligations to the company, says his lawyer, Kevin Kneupper. But Norling, of Spruce, contends that the system is now fully functioning (which Cummings disputes) and therefore that Cummings is responsible for ongoing lease payments. Spruce hasn’t responded to requests to stop sending him collection notices; Cummings has now filed a suit in California Superior Court accusing Spruce of violating the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act.

Cummings says Tredegar originally promised him he’d have no power bills and that the system would function for decades. “This is the whole thing with them auto-debiting your account,” he says. “People want to sell you stuff, they sign you up for auto-debit, and then they don’t honor the job.”

He’s right, in a way. Even if solar leases are not as popular as they once were, the last decade has seen an explosion of the as-a-service model, where customers don’t own things like software or music or even homes but instead pay a monthly fee. “Our as-a-service model allows consumers to access new technology without making a significant upfront investment,” Spruce said, in a March announcement that it had bought a portfolio of 22,500 solar leases.

These deals turn problematic when the company holding the lease keeps collecting monthly fees but, in an effort to keep costs low for investors, skimps on the actual service part of the deal.

Before Spruce returned my emails, I filed complaints with the New York State Attorney General’s office and with the New York Department of Public Service, which oversees regulation of the state’s utilities and rooftop solar. So far, neither has intervened. (A spokesperson for New York’s Department of Public Service told me that the agency has refunded more than $3.4 million to consumers this year based on complaints about solar billing issues.) A spokesperson for the Federal Trade Commission, which focuses on consumer fraud, said that my case falls outside the agency’s purview; a spokesperson for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau said that the conduct I described was likely covered by state and federal statutes that prohibit unfair or abusive practices.

“There’s a lack of regulation and it’s something that we have been trying to broadcast: the state is purely focused on mobilizing renewables, but at the expense of what?” says Daphany Rose Sanchez, executive director of Kinetic Communities Consulting, a company that helps lower-income customers in New York assess their renewable energy options. She’s had customers sign up for solar only to find that the company placed a lien on their home, rather than just on the panels, making it difficult to sell or refinance.

Regulators are eyeing their options, but they also don’t want to put in place barriers that might slow the development of a technology that, when it works, can be very good for society. “Consumers want solar panels, and nobody wants us to stop the availability of solar panels. ” says Tong, the Connecticut attorney general. “They don’t want the government making it more difficult or getting in their way.”

There's no slowing rooftop solar

Indeed, rooftop solar is booming. Around 6.4 gigawatts of rooftop solar was installed in the U.S. in 2022, which broke the record for the most small-scale solar capacity added in one year. Industry watchers expect the 2023 number to be even higher, after the Inflation Reduction Act increased a tax credit for rooftop solar panels to 30% of the cost of the project, up from 26% in 2020 and 2021.

The adopters of rooftop solar today may have fewer problems than the customers of the last decade; more people are now buying their systems outright, rather than leasing them, and the rise of battery storage has enabled homeowners to use more of the energy their panels generate, saving more money. What’s more, says Liu, the Wood Mackenzie analyst, as the market matures, solar companies are investing more into both selling systems and maintaining them.

Read more: Scientists Just Got A Step Closer to The Sci-Fi Reality of Building Solar Power Stations in Space

That doesn’t solve the problem that I and many others are facing—we can’t sign up for new solar systems or take advantage of new tax credits because we’re already stuck with older panels on our homes that are owned by companies that don’t seem to want to maintain them. Indeed, while solar does save money for a lot of people, for many people with older systems, the savings are pretty low; Zuckerman, the Maryland resident, says his savings come out to about $7 a month. And that’s even before the nightmare of dealing with a company that still has not fixed his panels. He, like many people I talked to for this story, says he wishes Spruce would just come and take the panels away so he could stop dealing with the headaches.

I haven’t gotten there yet—I like the idea of making some energy on my roof instead of buying it from a power company that is still burning fossil fuels. But I did like it better when I thought I could just have solar panels on my roof that were going to chug along and produce power without me having to constantly worry about squirrels or wires or billing issues. Now I’ve learned: with rooftop solar, someone has to be vigilant, and if the company maintaining your system won’t do it, you have to.

But vigilance is a hassle. Now that my 3G meter has been replaced, I can log online to Enphase’s monitoring system every day and see how much my system is producing, but even then, it seems almost set up to remind me of how little I can do as a person just trying to create some energy on my rooftop. On Sept. 21, for instance, the panels—which are still not working to full capacity—produced the most they have generated since the technician gave them a partial fix: 27.7 kwh. That means that even at its most efficient, the system can only generate about 18% less energy than my house uses on a daily basis.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com