On Wednesday, the second GOP presidential debate will take place at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute and will be televised on Fox Business Network (FBN), a cable channel with both conservative political and business credentials. FBN is newer and less controversial than the more prominent, politically charged Fox News Channel, but its turn in the spotlight makes clear a fundamental truth about the rise of cable news and its historic relationship to cable television’s bottom line. From the earliest days of cable, political programming has served the twin goals of giving the industry power and profits.

While Rupert Murdoch, who recently announced he was stepping down as the chairman of Fox Corporation and News Corporation, has unabashedly cashed in on the political and economic potential of 24/7 partisan echo chambers, such a strategy was not his invention. That credit instead goes to two entrepreneurs who came before him and made cable news into what it is today: Ted Turner and John Malone. Both men understood the profit and power they could amass by tapping into Americans’ television addiction with a promise that consumption itself could fuel democracy.

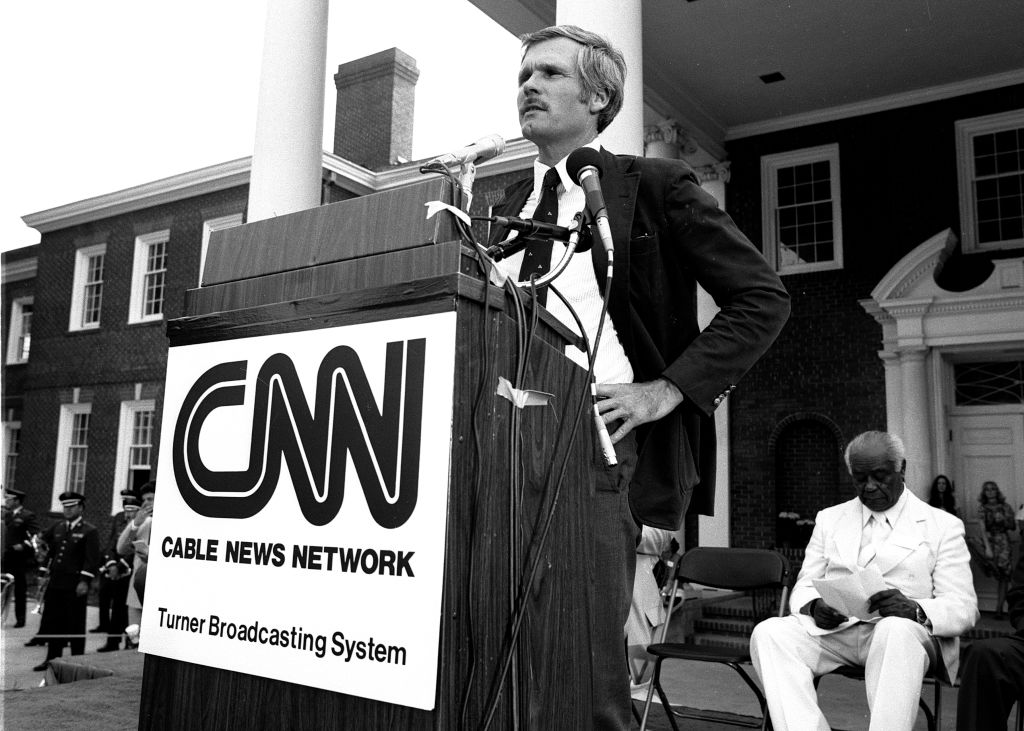

Read more: Ted Turner, 1991's Person of the Year

They took advantage of the displeasure of millions of Americans across the ideological spectrum who were unhappy with the television landscape during the 1960s. The three big networks—ABC, CBS, and NBC—exercised a monopoly over Americans’ screens. Yet, rather than lamenting its excesses, the networks’ critics denounced their limitations, from the dominance in newsrooms of elite, white, heterosexual men on the East Coast to the paucity of educational and public affairs programming.

Enter cable television. Its backers sold the new technology as a way to enable excluded voices to shape news and entertainment shows. Crucially, they argued that the route to more diversity was marketplace competition, which they defined as giving consumers the option to choose from an array of programing options. Over the next decades, cable pioneers embraced a very specific business model that chased niche audiences with the content they craved, ultimately transforming the very functioning of television news by tethering it to the metrics of the marketplace.

On June 1, 1980, CNN launched with a promise to deliver “understanding” and “peace” throughout the country and even the globe. In reality, Turner wanted to make money and found entrepreneurial ways to connect cable news to the business of cable television.

Immediately, cable advocates celebrated how a different approach to the news would help the industry’s bottom line as it fought against local regulations mandating rate caps and complicated franchise negotiations. An industry trade group lauded how CNN would boost lobbying efforts by moving “cable off the back pages and into the headlines,” thereby providing “credibility with our legislators and regulators.” And indeed, CNN provided an opportunity for elected officials in both parties to get the television time they craved, making them more sympathetic to the cable industry.

Fulfilling Turner’s promise to “make news the star” (and avoid overpaying celebrity anchors) also meant weaving in commentary and opinion shows to fill the 24 hours of airtime. The network then doubled down on more lucrative “soft news,” first introducing segments—and then eventually entire programs like Moneyline, Showbiz Today, and Larry King Live—dedicated to business, sports, and entertainment news. In the process, CNN reshaped the very definition of what national news could be: it wasn’t what journalists thought the public needed to know, it was what consumers wanted to see.

That’s why CNN also joined an industry-wide research collaborative aimed at gleaning information that would motivate advertisers, and then politicians, to embrace the cable dial and narrowcast—chasing smaller audiences of the “right consumers.” This research revealed that cable viewers drank more wine, bought more goods via mail orders, owned more video games, and used their American Express credit cards in higher volume than non-cable households. They were also more politically aware across the political spectrum. Compared to non-cable subscribers, “Cable Americans” were 28% more likely to vote, 50% more likely to work on a campaign and 69% more likely to donate money to a candidate or political cause.

Presenting this data to politicians sent a clear message: let cable thrive economically and elected officials could tap into more politically active viewers to benefit their own careers. It worked, and Congress passed legislation that eliminated rate caps and streamlined the franchising process in 1984.

In the aftermath, operators like TCI’s Malone, a ruthless cable visionary, saw CNN as one of the industry’s “crowned jewels.” In the late 1980s, when Turner overextended his credit and risked losing control of CNN, Malone convinced other major cable operators to join him in buying more equity to keep the channel in the hands of cable insiders rather than outsiders.

Time and time again, when legislators scrutinized their business practices, cable operators dangled CNN as evidence of the benefits of deregulation. In 1989, Sen. Al Gore (D-Tenn.) grilled Malone during hearings on rate hikes and vertical integration tactics, accusing TCI of being “hell bent on total domination” of the television marketplace. In response, Malone reminded senators that cable operators invested in channels like CNN and C-SPAN—which provided gavel-to-gavel of coverage of both the House and Senate—meaning far more news coverage for cable subscribers. Without directly saying it, Malone was also implicitly reminding senators that this coverage meant more television time for them to reach their constituents and build national, even global, reputations.

But Malone’s vision went beyond Turner’s view of cable news as a profit center. He saw cable’s success as hinging on giving viewers not just choice, but also a more personalized television experience—and that eventually included cable news. That’s why in 1996, he struck a deal to carry the new Fox News Channel in exchange for an undisclosed sum (rumored to be around $200 million) and an option to acquire a 20 percent stake in the business. The savvy—and politically conservative—Malone correctly recognized the moneymaking potential of Murdoch’s vision of balancing out perceived liberal media bias and tapping into a hungry “right of center” audience.

Two years later, Malone discussed the future of television news in a competitive cable news environment (which also included MSNBC, launched in 1996) with Walter Cronkite. Malone celebrated the profit potential of the 24/7 news channels that had emerged as brands targeting different demographics. He even foreshadowed the profitability of today’s media environment, touting a future in which business and technology would advance to the point that viewers could “hit a button and up comes thirty minutes of the news exactly the way you want to see it.”

The legendary CBS anchor voiced concern that consumerism was poised to overrun citizenship and threatened to leave Americans without the knowledge they needed “to perform their role in democracy.” Malone, however, derided such thinking as elitist. “The consumer is king,” he asserted. He trusted viewers to “demand convenience, accuracy… and quality.”

From the beginning, cable news tapped into civic frustrations with the limits of broadcasting, but its goal was never to advance democracy. Instead, cable news had two purposes: making money and fostering the deregulation of cable television. To convince lawmakers to unshackle the industry, executives sold the idea that giving audiences what they wanted—and therefore maximizing profits—could deliver a more robust landscape and a better informed citizenry. Many elected officials eagerly bought into that promise because expanding television access served their own agendas as well.

Read more: What to Know About Rupert Murdoch’s Successor Lachlan and All His Other Children

Yet, the rapidly expanding media landscape of the last 30 years has exposed that while more media means the information citizens need is available, trusting the market has produced profitable echo chambers and information silos that, by design, drown it out. That’s why Murdoch bought the Wall Street Journal and then launched Fox Business to grow his media empire. He wanted to strengthen the bonds between conservative media outlets that reinforced the messages, ideas, and viewpoints that his target right-leaning audience wanted to hear. The result is a polarized political landscape with the left and right living in fundamentally different media worlds.

CNN recently released a poll that found that 69% of Republicans and Republican-leaning voters question the legitimacy of the 2020 election, despite all evidence to the contrary. That’s why it is fitting for the second Republican debate to play out—as the first one did—on a channel that makes clear its priorities: throwing red meat to conservative voters in the name of making money for its owners. This sobering reality reflects how cable has remade the political world and makes clear the profound democratic challenges facing the country today.

Kathryn Cramer Brownell is Associate Professor of History at Purdue University, Senior Editor of Made by History, and author of 24/7 Politics: Cable Television and the Fragmenting of America from Watergate to Fox News and Showbiz Politics: Hollywood in American Political Life. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Kathryn Cramer Brownell / Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com