Harriet Tubman is the most famous “conductor” of what’s known as the Underground Railroad, the network of safe houses that helped enslaved Black Americans in the South escape to the northern United States and Canada in the 1850s. But she did not come up with the term 'underground railroad,' and the man who did has been largely forgotten by history.

The phrase dates back to a different operation of escapes organized by Thomas Smallwood (1801-1883), a Black shoemaker who worked near the U.S. Capitol building and a father of four children.

Between 1842 and 1844, Smallwood helped the enslaved Black servants of government employees escape to Canada and wrote about these feats under a pseudonym for an abolitionist newspaper in Albany, N.Y., which was along the escape route he was using. (Slavery wouldn’t be abolished in Washington, D.C. until 1862.)

In the new book out Sept. 19, Flee North: A Forgotten Hero and the Fight for Freedom in Slavery’s Borderland, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Scott Shane traces the first mention of the underground railroad to an Aug. 10, 1842, column in the Albany paper Tocsin of Liberty, written by Smallwood under the pen name Sam Weller:

It was your cruelty to him that made him disappear by that same “under ground rail-road” or “steam balloon," about which one of your city constables was swearing so bitterly a few weeks ago, when complaining that the “d—d rascals" got off so, and that no trace of them could be found!

Writing under a pseudonym kept Smallwood from becoming a household name in the U.S. This column is one of the jokey letters he would address to the wealthy individuals who owned the escaped enslaved people, which the paper sent to anyone mentioned in the text. This letter was penned to Thomas A. Scott of Washington, D.C. regarding Henry Hawkins, a man Scott enslaved who was on his way north.

A few weeks later, Smallwood used the term 'underground railroad' again in an Aug. 24, 1842, column responding to a physician named James G. Coombs’ who posted a “wanted” notice for two men he enslaved in Washington, D.C. “I would just hint to him, by way of caution, that the secret of the ‘underground rail-road’ has never been communicated to anyone but the PRESIDENT and his CABINET.” In later columns, Smallwood would facetiously refer to individuals looking for their enslaved runaways “to apply at the office of the underground railroad.”

Read More: The Unsung Hero of the Underground Railroad

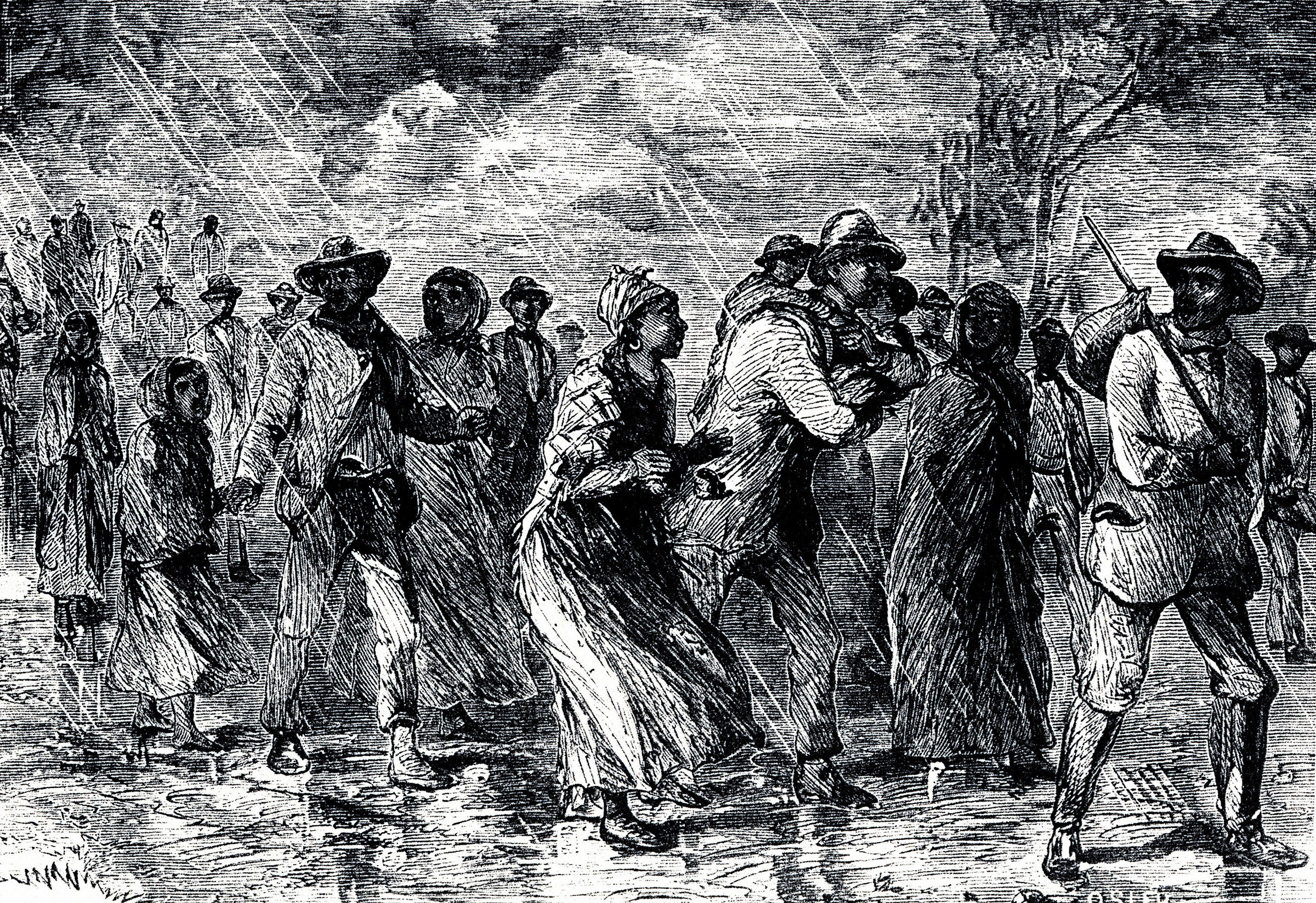

While Tubman would lead people from the South up through fields and swamps in rural areas, Smallwood was helping Black Americans escape from primarily urban areas, working with a white abolitionist Charles Torrey. Up to 20 enslaved people would be packed into horse-drawn covered wagons that would take off in the middle of the night and head north from Baltimore and Washington, D.C., primarily. “That's one thing that Smallwood remarks on, is that many of the people who came to him saying ‘help me escape’ were motivated because they feared they were about to be sold South,” says Shane. “He hoped to demoralize [the enslavers] and convince them that enslaving people just would not pay off, and that they have to hire laborers.”

Smallwood helped hundreds of enslaved people escape, collectively. Shane estimates that one wagon load of enslaved people was worth about $200,000 in today’s dollars. While the escapes that Smallwood orchestrated were a fraction of three million enslaved people in the United States at the time, it still caused a lot of embarrassment and garnered press attention because it was happening in the nation’s capital. Smallwood’s system of escapes “did not undermine the slave system. That would take a little longer, but it had quite an impact on the people in those cities at that time,” Shane says. But “for the hundreds who they helped free, it completely changed the trajectory of their lives, their children's lives, their grandchildren's lives.”

Smallwood eventually left the country himself, arriving in Toronto, Canada, on July 4, 1843. In his 1851 memoir written under his own name, he reflected on the symbolism of being a man who helped people escape to freedom embarking on his own journey on Independence Day: “Here, I was on Canada’s free soil, and I may rejoice and give thanks to God in honor of that day, it being the day on which I first put my feet in a land of true freedom, and equal laws.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com