Nazanin Boniadi is an Iranian-born human rights activist, actress and 2023 Sydney Peace Laureate.

The Islamic Republic of Iran was built upon bricks of patriarchal misogyny. One of the first acts of the revolution’s leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, when he took power in 1979, was to reverse women’s rights in marriage, child custody and divorce. This included lowering the legal age of marriage for women from 18 to 9, and girls this young can still be married in Iran today.

Iranian women have not only been forced to veil but have been forbidden from dancing or singing solo in public, riding a bicycle, attending matches in sports arenas, becoming judges or president. They must sit at the back of the bus and can travel abroad only with their husband’s permission. Their court testimony and inheritance are deemed worth half that of men. They are among the very few women in the world whose grandmothers had more rights.

Nothing scares the Islamic Republic’s rulers more than independently minded women, and they know that, one year after the death of Mahsa Jina Amini in police custody, the revolutionary fire still blazes in the hearts and minds of Iranians. More than just a condemnation of the draconian dress code that Amini had been charged with violating, “Woman, Life, Freedom” is a powerfully synergetic slogan that acknowledges the importance of women’s rights in the quest for a normal life and fundamental freedoms for all citizens.

Read More: Mahsa Amini's Death Still Haunts the Iranian Regime

The theocracy’s brutal forces may have cleared the streets, but the people’s defiance is far from over. Female journalists Nazila Maroufian and Sepideh Gholian, continue to defy the regime despite multiple imprisonments. Mahmonir Molaei-Rad, the mother of 9-year-old aspiring inventor Kian Pirfalak who was killed by security forces, lives under house arrest for continuing to seek justice for her son. Dozens of Iranian female athletes have competed without compulsory hijab, prominent actresses have publicly removed their veils in protest, and hundreds of thousands of women continue to flout the hijab in major Iranian cities.

Mahsa’s killing galvanized a broad-based, pro-democracy uprising. Today millions of university students, worker’s unions, dissidents, ethnic, religious, sexual and other minority groups recognize that the status of women and girls is inextricably bound to the inclusive democracy they seek. They understand that you cannot divide women’s rights from human rights and universal dignities.

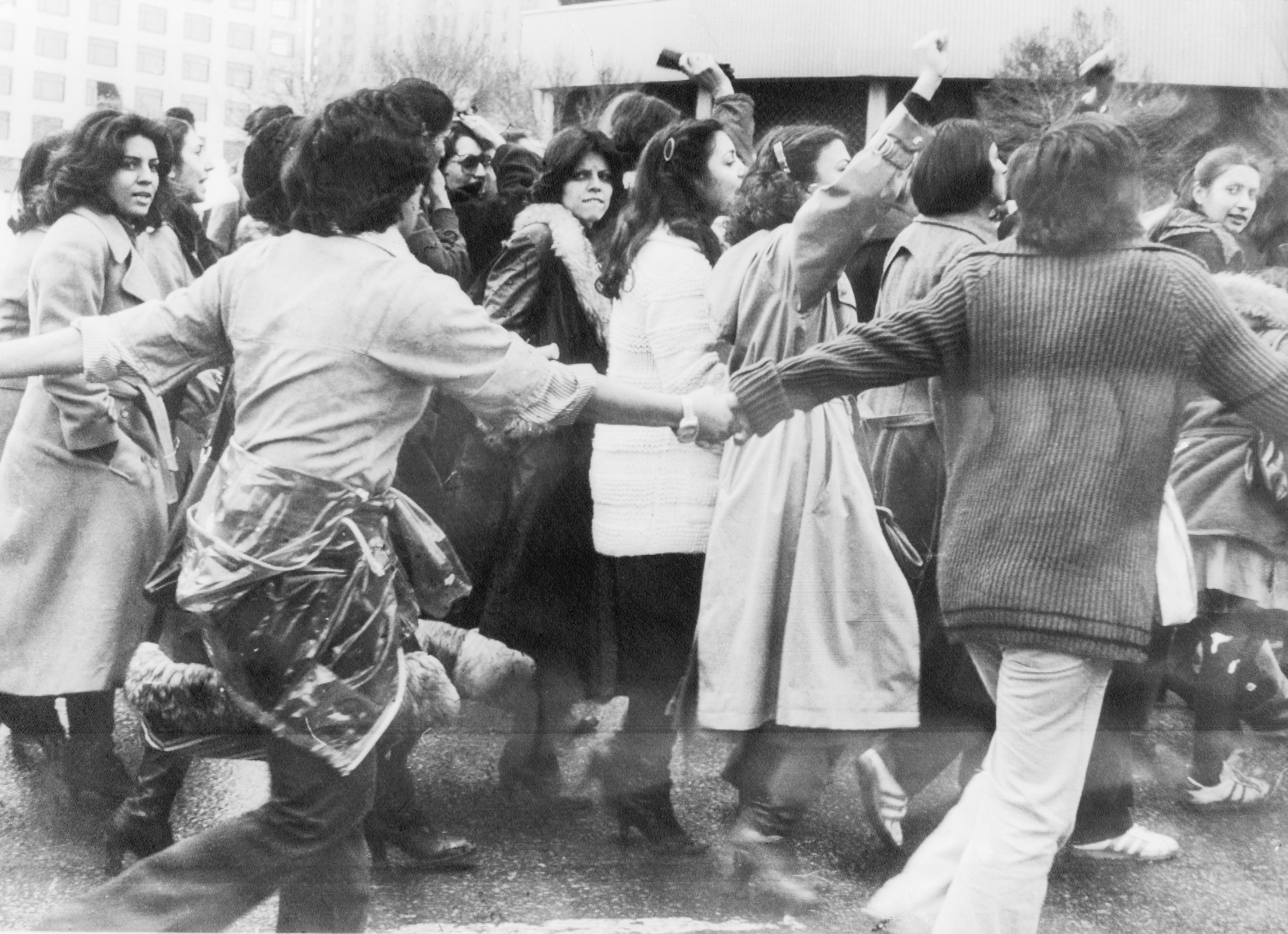

In the aftermath of the 1979 Revolution, too few Iranian men showed solidarity as the regime ransacked the rights of their wives, mothers, daughters and sisters. But over the last year, they have stood united with Iranian women against a gender apartheid regime that maintains power by silencing everyone who doesn’t share its intolerant, Islamist ideology.

Pop singer Mehdi Yarrahi was jailed in August for his song “Roosarito” (“Your Headscarf”) in which he champions women to remove the mandatory veil. Prominent dissident Majid Tavakoli appears to be days away from having to serve yet another lengthy prison sentence for his liberal advocacy. Images of hospitalized and intubated 31-year-old protester Javad Rouhi, — tortured to death while imprisoned — are eerily similar to the viral images of Mahsa last year.

Indeed, while much of the international coverage of Iran’s protests in the past year have focused on the role of women, the vast majority of the more than 500 Iranians who have been killed by authorities during these protests have been young men. The movement’s rallying cry has captured the national aspiration.

Nowhere is this notion reflected more profoundly than in singer and songwriter Shervin Hajipour’s song “Baraye” (Because of) — perhaps the most compelling manifesto expressing the longings of the Iranian people — that won the inaugural Best Song for social change Grammy in 2023. The song became the international anthem for “Woman Life Freedom,” channeling societal discontent with lyrics that touched on themes of poverty, economic hardship, corruption, environmental mismanagement, human rights abuses, gender inequality and a yearning for an ordinary life.

Mahsa Jina Amini was young, a woman, a member of religious and ethnic minority groups. She represented Iran’s vibrant diversity — the antithesis of the homogenous, intolerant, geriatric, male, Shia clerics who rule the Islamic Republic. History has shown us that when women are on the frontlines, democratic movements not only have a higher chance of success, but also a better outcome for all who seek their rights and their freedoms. The centrality of women’s rights in this movement only strengthens the objective of a free, secular and democratic Iran. That’s why Iran’s “Woman Life Freedom” revolution not only endures, but is one of the most important and promising political movements in modern Middle East history.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com