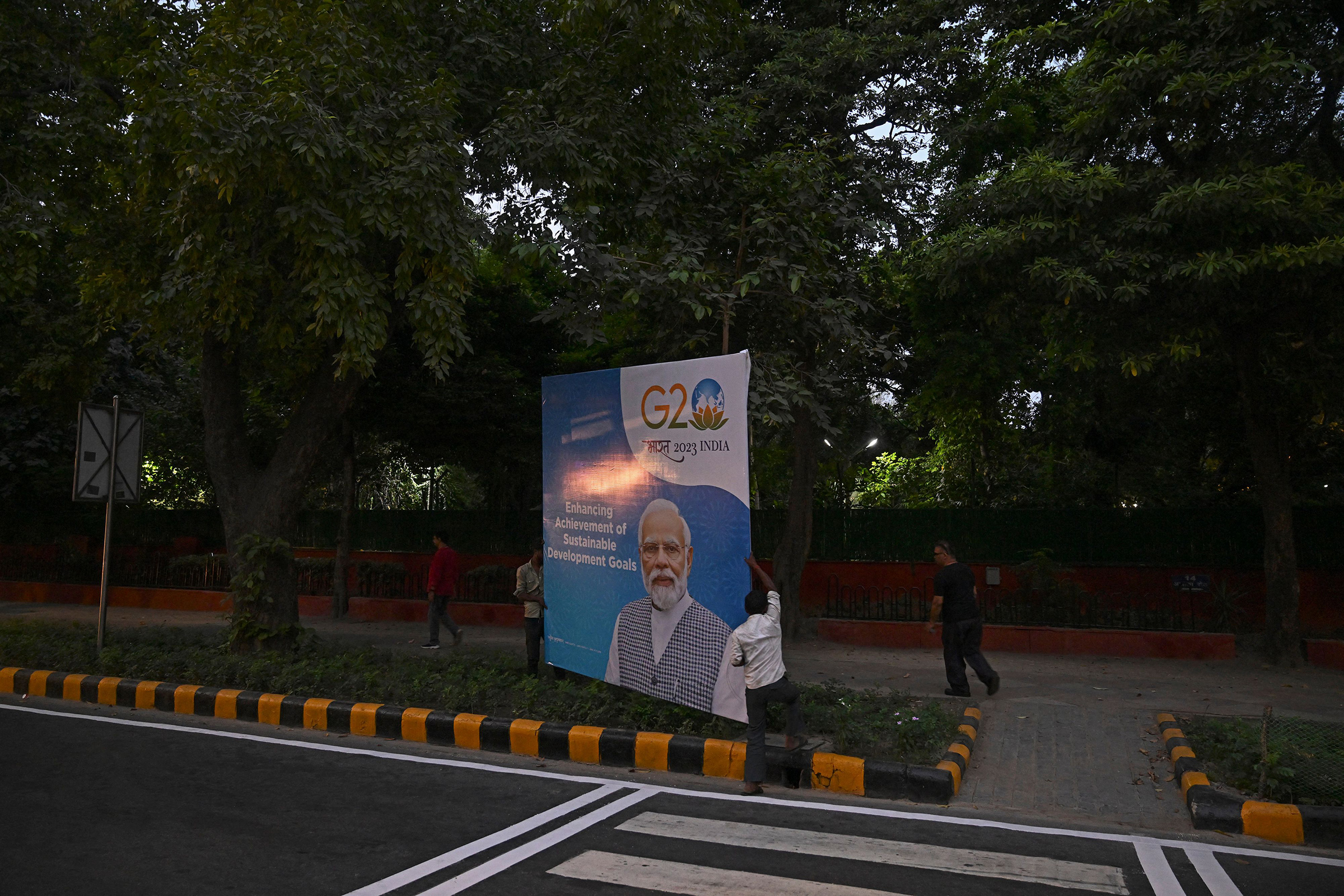

If Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s state visit to Washington earlier this year was cast by the Indian prime minister’s boosters as confirmation of his popularity in the United States, the G20 meeting in New Delhi this weekend is being promoted as consecration of his status as vishvaguru—a mentor to the world. India may be hosting by virtue of gaining the group’s rotating presidency, but the center of attention—at home and abroad—is the man some exalt as the hope of the democratic world and others decry as a strongman. Either way, to equate India—a federal union of more than two dozen states—with one individual is to obscure the many voices of opposition that are questioning Modi’s record, challenging his sectarian ideology and factious politics, and advancing an alternative vision of India that is competent, open, and humane.

One of the most commanding opposition voices is the rich baritone of Palanivel Thiaga Rajan. In the maelstrom of Indian politics, PTR, as everyone calls him, is an improbable figure. Regally portly, imperturbably placid, and savagely articulate, the man who until recently was responsible for managing the finances of Tamil Nadu—India’s second largest economy—is now on a new mission: to make Chennai, the capital of his state, the next IT capital of India. PTR did not seek this assignment. His performance as Tamil Nadu’s finance minister was so consummate that it earned him a national profile—a rarity for a politician from southern India, the more industrious and prosperous yet politically less powerful half of the country. As the manager of an economy almost twice the size of Hungary’s, PTR was everywhere, forcefully demystifying recondite economic jargon for the general public, deflating Modi’s claim to be converting India into an economic superpower, and defending India’s secular character from the assaults of the Hindu-first politics of Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Read More: ‘Bharat’ or ‘India’? The Controversy Over Some Hindu Nationalists' Push to Rename India

When I met him at his sprawling government mansion in Chennai earlier this year, PTR told me that the suffering of ordinary people during the financial crisis of 2008, when he was a banker, haunted him. If ever he was in a position of authority, he told himself, he would prioritize the least powerful. And that is what he did in the pandemic, allocating billions to fight COVID-19, before providing 8 million women in Tamil Nadu a monthly cash transfer of 1,000 rupees—all while reducing the state’s deficit and debt-to-GDP ratio. But the velocity of PTR’s rise and his closeness to the leadership of Tamil Nadu’s ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) party also drew the resentful notice of older colleagues.

Until 2016, when he won his first election to the state legislature, PTR had been a privileged yet largely unknown private citizen. He was born into an aristocratic family that traces its origins to the Chola Empire, which dominated southern India and east Asia in the 11th century. PTR’s grandfather, Sir Ponnambala Thiaga Rajan, was one of the most pre-eminent politicians in British India. Educated at Oxford and trained as a barrister in London, the old man had made enemies of hidebound Hindus by appointing members of lower castes to high-ranking positions in some of the most venerated Hindu temples in southern India. But his late father, Palanivel, a much admired lawyer and politician, was determined not to build a political dynasty.

Born in 1966, PTR was expected to work hard, get into the best schools and universities, and settle into a high-paying job. And that is what he did. Exiled to boarding school at age six, he attended the National Institute of Technology in India and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States, before taking a job as a banker at Lehman Brothers in New York. By his mid-thirties, PTR had made his first million, married his American girlfriend, Margaret, and fathered a son. The man now regarded as one of the most scrupulous Indian politicians of his generation had no clear plan to return to India, much less to run for public office. Then, in 2006, he received news that his father had died of a heart attack. An only child, he moved to India to be near his elderly mother. Lehman opened an office for him in India, an unprecedented arrangement that collapsed with the firm in 2008. Now jobless (having turned down an offer from the DMK to run for his father’s vacant seat), PTR moved to Singapore to work for Standard Chartered Bank. His family remained in India.

This time, distance deepened his attachment to India. PTR followed its politics closely and observed Modi’s untrammeled rise from provincial politics to national prominence. The way to challenge Modi, he felt, was to fortify the federal structure of India: only the states could most effectively check Modi’s power in Delhi. In 2015, he gave up banking, returned to India and a year later ran for Tamil Nadu’s state legislature from the historic temple town of Madurai. Though his party lost, PTR took the seat by a small margin. And for the next five years, he devoted himself to modernizing the party’s IT wing. At the next election, in 2021, the DMK won decisively. PTR, to the astonishment of his colleagues, was given the finance ministry—one of the weightiest portfolios in government, and a system governed by its own archaic rules. “I want to make this department efficient and modern,” he told me. “I want it to be able to function on autopilot, should the need arise.”

The job served as a showcase. With it came membership on India’s powerful panel on goods and service taxes (GST Council), where he began working closely with India’s finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman. Even as he castigated the social policies of Sitharaman’s boss, he acquired a reputation in Delhi as a consensus builder on economic policy, effectively emerging as the most influential voice in the GST Council. (The Modi government even agreed to convene the GST Council in PTR’s hometown of Madurai.) Just over two years into his job, PTR had simultaneously established himself as one of the most trenchant national critics of Modi and as a bridge between the federal government and the states. At the same time, he attracted an enthusiastic support base locally. At a public meeting in Chennai one February evening, I saw women cheer every sentence of his speech and mob him affectionately afterwards. In a political culture animated by envy, PTR was flying at a dangerously high altitude.

This summer, a mysterious audiotape was leaked to the press by the head of Tamil Nadu’s BJP unit and broadcast on every news network. In it, PTR could be heard complaining about corruption in his own government. A politician privately appalled by graft is a rare creature, but PTR denied the voice was his—and then put on a detailed presentation demonstrating how it could have been created using sophisticated AI tools.

The integrity of Indian democracy, already deformed by a deluge of disinformation and illicit cash, faces a grave threat from advances in AI, as do other Western-style democracies. In PTR’s case, his allegation of duplicity was essentially vindicated in August, when the Supreme Court of India dismissed a petition demanding a probe into the tapes, saying they amounted to “hearsay” and had no “evidentiary value.” But that was only the legal outcome. Politically, the damage had been done.

In May, PTR was relieved of his duties as Tamil Nadu’s finance minister, and moved to the ministry of Information Technology and Digital Services. Cabinet reshuffles seldom provoke controversies, but this one triggered a torrent of criticism. When I reached out to him shortly after the reappointment, however, PTR was unfazed, even cheerful with the demotion. He had modernized the finance ministry and upheld the promise to balance the budget and channel cash to women. “Now, this new role is a blessing,” he said.

PTR’s command of economics, which had won him the grudging respect even of the BJP, is no match for his passion for technology. Weeks into his new job, he was on a tour of the US, arriving in New York just before Modi’s state visit to drum up investment. Silicon Valley is replete with CEOs from Tamil Nadu, PTR said with some pride, and foreign investors, tech companies, and manufacturers are now looking at what he reminded me had been the first Indian state to set up a ministry dedicated exclusively to IT affairs, only to fall behind Hyderabad and Bangalore, the two cities where almost all the major transnational tech companies are headquartered. “I am going to drag Chennai ahead of those two cities,” he told me. “Just wait and watch.” Modi may absorb all the credit. But the hard work of raising India up is being done by those the world does not yet know.

Correction, Sept. 11

The original version of this story misstated the name of PTR's late father. It is Palanivel, not Ponnambala.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com