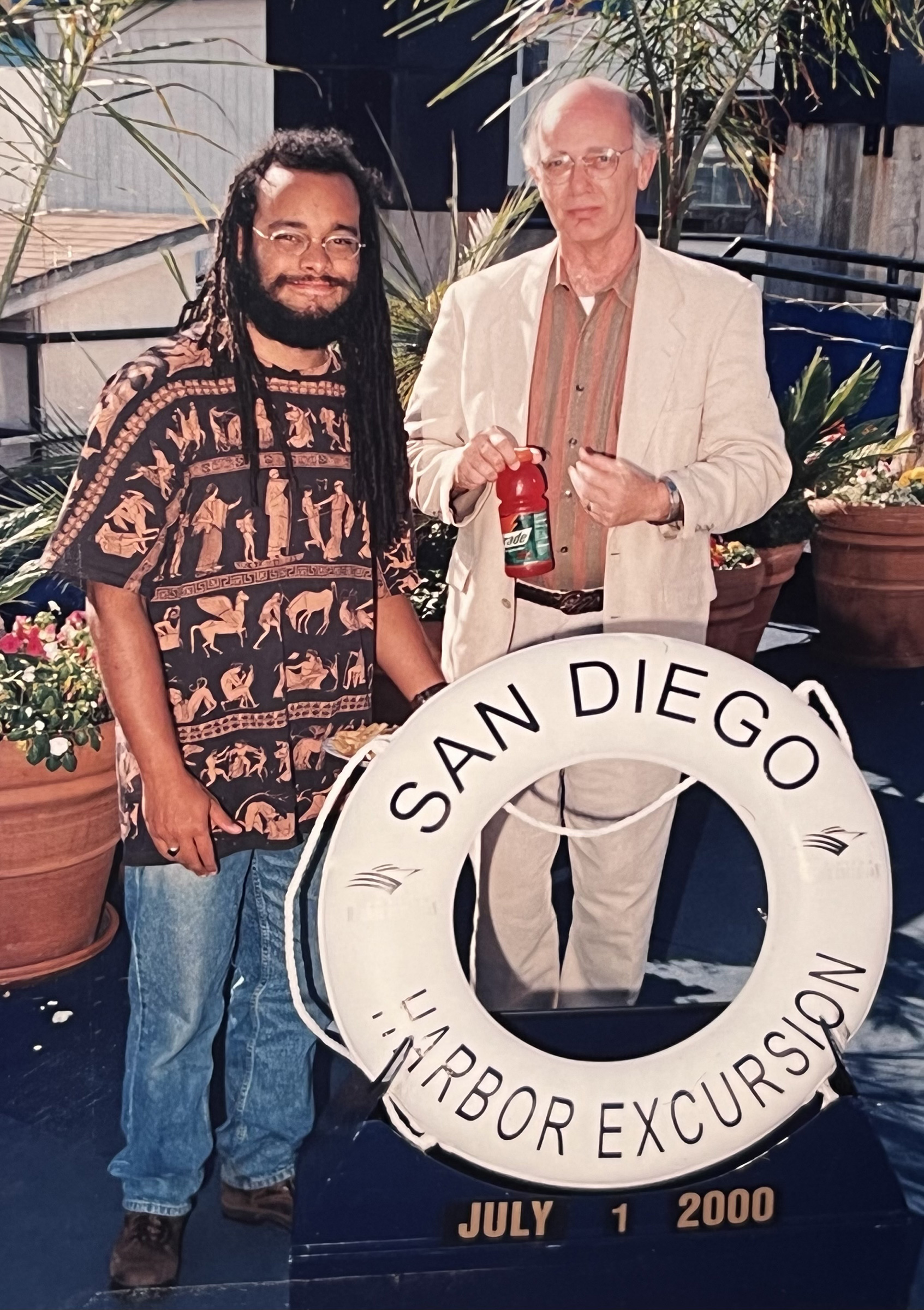

August 11, 2023 marked the first time my father, Edwin LeRoy Goff, could have celebrated his birthday while holding his grandson. He died on April 22nd, 2022, roughly five months before my son was born. When he died, my father knew that my wife and I were expecting a boy. That the boy’s middle name would be LeRoi (my dad’s preferred spelling). And that my dad had work to do.

“Get the damned CPAP!” I scolded him that March. “You only have to make it to October now!”

It was our running joke for years—the kind of thing that has to be a joke because it cannot be said plainly. He would laugh at whatever life-extending behavior I demanded. Sometimes he would confess a secret plan to get healthier. But he never followed through. And then he died.

I was lost. I knew I needed to do something to honor him, something as big as the hole his absence left, but I had no sense what that should be, which left me feeling not entirely sane. Because, while I was struggling to find how to honor him, I was also wrestling with a commitment I made to my growing family: To give up my father’s name.

To be fair, losing my father’s name was not technically the commitment. The commitment was to create one family name with my wife. In our case, that amounted to the same thing. At 15, I decided it would be sexist to ask a woman to take my name in marriage. In talking with my father, whose marriage to my mother fell just 18 months after Loving v. Virginia made it legal, I asked if he thought marriage naming conventions were sexist. He said he'd never considered it. “But I probably should have,” he admitted. That endorsement locked me into changing my name.

Fast forward a couple decades, I cavalierly told my then girlfriend (now wife), “If we get married, I’m taking your name”—a path followed by roughly 3% of men in straight marriages (and nearly half of men in non-straight marriages). Without hesitating she replied, “Because it’s somehow less sexist for both of us to have my father’s name?” Which vaporized that bit of teenage brilliance.

Read More: 'Lucy Stone, If You Please': The Unsung Suffragist Who Fought for Women to Keep Their Maiden Names

So, we got curious about other options. Hyphenation felt clunky for us. She proposed we keep our names, something increasingly common among academic couples. But that ruled out having one family name—defeating the point. Ultimately, we decided on a single new name for us both. Meaning that, as I spent my first birthday without him, my first Eagles Pre-Season, my first Perseid meteor shower, I was grieving my first best friend while perversely filing paperwork to lose yet another tie to him.

I did not worry that he would disapprove. When my parents were not sure how to arm the child of a White father and Black mother for the racism of the north, they chose to give me the middle name, “Atiba,” a Yoruba word for wisdom—one who seeks understanding. The name my wife and I chose, “Solomon,” echoed that commitment to teaching the pursuit of wisdom, a commitment my father spent his career pursuing as a moral philosophy professor. Moreover, he had given his explicit blessing more than six years earlier. Still, it felt like betrayal. And I was still lost.

Read More: To Protect the Next George Floyd, We Must Remove the Threat of Police Violence from Everyday Life

After months of agonizing over whether or not to finalize the move from “Goff” to “Solomon,” I asked a question my father sometimes wielded against hard problems: “Who has faced this before?” Again, my wife was kind enough to have the answer. “Um…women.” Right. In the U.S., more than two-thirds of women still change their names in straight marriages.

I spoke with a friend who had lost her father after changing her name. Did she also feel remorse or shame? Turns out, no. Her response, and the responses of other women I unscientifically surveyed, was that changing their names was entirely untethered to their obligations to their dads. Many assumed that marriage meant a name change—and that they would outlive their parents.

Why was I so conflicted, then? Was I just worried about violating gender expectations? Maybe. While some colleagues applauded the idea (a bit like me at 15), one person close to my father called it “disgusting.” My concern that people would see the name "Phillip Atiba Solomon" as dishonoring my father was not entirely baseless. Still, when I took the time to be curious about it, that fear was not at the pit of my internal conflict. Instead, it was losing his name—without having figured out how to honor him.

It was some comfort that the name itself wasn’t my problem. It wasn’t the solution either. I investigated raising funds to name things after him. Maybe that will be it. Before bed, my wife and I now share things we think he would have noticed. It’s nice to bring his memory back to us each day. It also does not feel like the full measure.

The truth is, I haven’t figured it out yet. Feeling like a failure as a son, and worried I’d be one as a father, I asked my therapist how children learn to honor their parents and love themselves. His answer stunned me. “Curiosity,” he said. Parents often feel most honored when their children are curious about their lives. Children learn to love themselves by seeing their parents love them. If parents are curious about their children, kids learn that they are worthy of that kind of interest.

Moral philosophers tend towards analytic certainty, but my father was a philosopher in a different mode. Long before Ted Lasso made it cool, my father was the single most curious person I have ever met, both in being odd and in being interested in the world—though mostly the second thing. There was kindness in it. He would turn his curiosity towards every new person he met, which absolutely made him the worst person to run into on the way to the bathroom. But he was also reflecting to people that they were worthy of someone’s attention. He was being a mirror for them to love themselves through.

I am still lost without him most days. Still trying to find a path to honor him. But at least my dad packed me with provisions for the journey. The curiosity he gifted me helps me discover new morsels of him in the books he loved and the artists that nourished him. It delivered me from many teenage certainties, solved my naming and gender conundrum, and helps me parent my son a little like my father did me.

It's still not enough. It is, though, what I owe him on my way to figuring out what enough is.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com