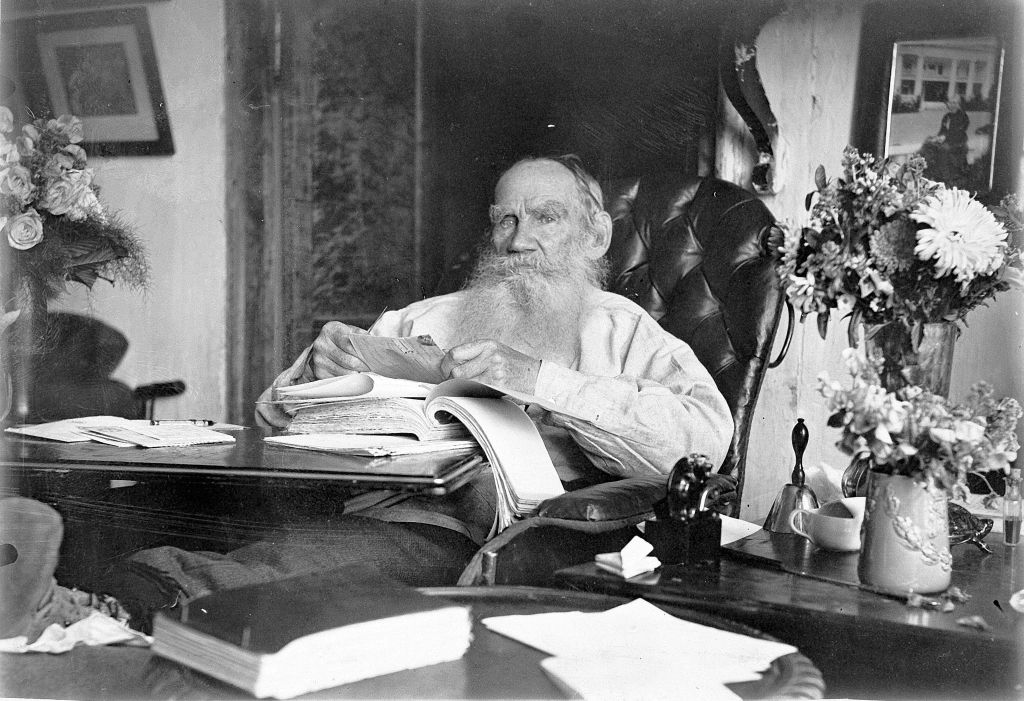

The geopolitical world teeters on the brink. To understand it, nothing is more necessary than a profound imagination. And that brings to mind Leo Tolstoy.

In War and Peace, Tolstoy writes that Count Fyodor Rastopchin, a general and statesman, “had known for a long time that Moscow would be abandoned, but had known it only with his reason, while with all his soul he had not believed it, and he was not transported in imagination into that new situation.” Rastopchin in this particular case had a prescient intellect. But because he could not vividly picture in his mind the fall of Moscow to Napoleon and the subsequent abandonment of the city by its inhabitants, he was helpless when it actually happened. Reason and analysis are not enough, as I have learned in over four decades as a foreign correspondent and geopolitical analyst. True clairvoyance, if such a thing is even possible, is really about a powerful imagination, which is essentially literary.

Pearl Harbor, 9/11, the rapid fall of Kabul, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the aborted march on Moscow by Wagner mercenaries, and Vladimir Putin’s likely retaliatory assassination of Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin were all, at least in a theoretical and analytical sense, somewhat predictable by experts beforehand. But they were also unimaginable, so we were all caught by surprise. Knowing something and actually believing it can be two different things. The best example I know concerning this category of mistake happens to be my own. I knew and even warned that Iraq was an artificial state, perhaps prone to chaos. Nevertheless, my problem was that while Iraq’s tyranny was something I had vividly experienced on the ground there during several visits in the 1980s, Iraq’s chaos was something I could only know theoretically until I returned to Iraq in 2004 and 2005 embedded with the U. S. military. Thus, in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, burdened by my awful memories of Iraq under Saddam Hussein, but unable to actually imagine the Iraqi anarchy that I had speculated about, I supported the Iraq War, and, in the manner of Tolstoy’s Count Rastopchin, I would soon find myself in my own eyes “ridiculous, with no ground under his [my] feet.” (All quotes from Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky's translation of War and Peace.)

One of the many things I learned the hard way from Iraq was that simply because you cannot specifically imagine an occurrence or situation doesn’t mean it won’t happen. This sounds obvious but it is not. What is now unimaginable in Russia, Iran, and quite a number of other places may in fact come to pass in the coming months or years. This is because not only is the Russian regime weak and increasingly unstable, but so are quite a few other regimes. We live at a time of tired authoritarian systems that are just as likely to give way to chaos as to democracy; if not to new forms of authoritarianism. The old question of the political philosophers, from Aristotle to Hobbes, is once again upon us: How to build new systems of order without succumbing to tyranny? Because this is such a messy, at times impossible, enterprise, we must prepare for dramatic surprises. As Tolstoy intimates, great events are the summation of phenomena that, because they are so complex and numerous, and also involve the Shakespearean passions of human beings, remain “inaccessible to the human mind.” And what makes them even more incomprehensible, according to Tolstoy, is that the “intrigues, aims, and desires” of the historical actors often lead to outcomes different from what they intended.

Read More: What Prigozhin's Death Reveals About Putin's Russia

As I write, Russia is at a crossroads, a place where it has not been for 70 years when Stalin died. Then the fate of the whole Soviet empire was in question, as the East European satellite states were all subservient to the Kremlin. Predicting that Nikita Khrushchev would triumph and lead the empire to gradual de-Stalinization was certainly not obvious beforehand. Now we are again talking about the fate of the Russian empire, with its various minorities and spheres of influence stretching east to the Pacific and south to the Middle East, not to mention its effect on Europe. The difficulty in prediction—what necessitates a Tolstoyan imagination in the first place—is that Russia has historically been a weakly institutionalized state, especially when compared to China, a very different authoritarian behemoth with thousands of years of bureaucratic history behind it. Putin has accumulated more power than any Kremlin leader since Stalin, and yet behind—and beyond— that façade may lie an utter void. State collapse, a shaky collective leadership, civil war, liberal democracy, a new dictator even more nationalist than Putin, or Putin himself growing into a true totalitarian tyrant may all be real possibilities. Russia at some point could actually become a low calorie version of the former Yugoslavia. Indeed, throughout the 1980s experts speculated openly about the uncertain future of post-Tito Yugoslavia. But all were, nevertheless, shocked by the ethnic war and collapse of the federation that followed in the 1990s. Neither should we be shocked by a complete disintegration of the Russian empire, with warfare across the breadth of the supercontinent, a rump and unstable Russia left to cause Europe a permanent nightmare, and Chinese power expanded deep into Eurasia; or conversely, an economic collapse inside China itself that leads to social upheaval. Nobody should think any of this can’t happen.

Iran represents another tired, teetering regime of great consequence, with far-flung ethnic regions, that could affect areas well beyond its own borders. The Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, is 84 and in ill health. His succession could be problematic. Iran has already faced widespread political unrest against the regime in 2009, 2019, and 2022, not to mention other simmering revolts. The regime’s base of support is exceedingly narrow. As has been said, the situation is like a group of North Koreans governing a country of South Koreans. Like Russia, anything is possible. Before the Shah fell in 1979 it was impossible to truly imagine a regime other than his, despite the warnings of many experts about his low popularity. After he fell, for decades it became impossible to imagine any regime beyond that of the ayatollahs. But just last fall, in the midst of massive anti-regime protests ignited by the violent death of a woman, Mahsa Amini, while in the custody of the so-called morality police for incorrectly wearing the hijab, it suddenly became possible to vividly imagine a new Iran.

And with a new Iran, over time there could even be a new Iraq. Iraq’s weakness and extreme instability as a democracy in the aftermath of the U.S. invasion in 2003 has been to a significant extent a function of political interference and intrigue from Iran. But were that situation ever to end, and were Iran to turn inward to address its myriad of political and economic problems in advance of joining the global community, Iraq could stabilize and dramatically transform before our eyes. One’s entire image of a country and its politics, as well as one’s expectations about its future, can turn on a dime, which should make us embrace Tolstoy with his complex interplay of unintended historical fate and human agency, and make us wary of the conventional wisdom.

Conventional wisdom relies on linear thinking, that is, on the continuation of current trendlines. But great events are often great because they manifest zigs and zags. One of the ultimate follies of conventional wisdom that I am aware of was the fantastically grand buildings designed as the administrative heart of British India by Sir Edwin Lutyens in New Delhi, which were all constructed in the interwar years with the implied assumption of eternal colonial rule. Yet the British empire in India came crashing down just a few years later.

The same might be true of a number of Arab dictatorships. To assume that the failure of the Arab Spring automatically means continued autocracy is another example of linear thinking. While expecting new democratic outcomes might be fanciful, individual autocracies might weaken into a number of competing factions, in which case various groups in society might be consulted more on policy. Such consultative regimes already function in the royal systems of Oman, Jordan, and Morocco. Even the more rigid autocracies of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states feature consultation with elements of their populations. Change will have to come in one form or another. After almost a decade in power, the military regime of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi already seems exhausted and near a dead end, unable to generate the level of economic growth and entrepreneurship demanded by a growing and youthful population. With Egypt’s underground water table diminishing and its access to upstream Nile water potentially threatened by Ethiopia’s Renaissance Dam, Egypt (as well as Pakistan) are examples of hard regimes that hang on desperately to power in the face of an increasingly hostile natural environment.

Climate change that disrupts agricultural cycles, coupled with information technology advancing at warp speed, is simply going to unravel political systems across the globe that cannot measure up. It is getting increasingly harder to be a dictator these days, even as the weakness or absence of bureaucratic institutions make democratic change problematic in many countries. The future is more mysterious than ever.

The poet John Keats urged us to be “content with half knowledge,” which echoes Tolstoy’s observation that much of what will happen in international affairs remains “inaccessible to the human mind.” But neither should we lose hope. As Keats wrote,

And other spirits…are standing apart

Upon the forehead of the age to come;

These, these will give the world another heart,

And other pulses. Hear ye not the hum

Of mighty workings? –

Listen awhile ye nations, and be dumb.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com