A Cantonese language advocacy group in Hong Kong stopped operations after local officials raided the family house of its chairman last week over an essay published three years ago.

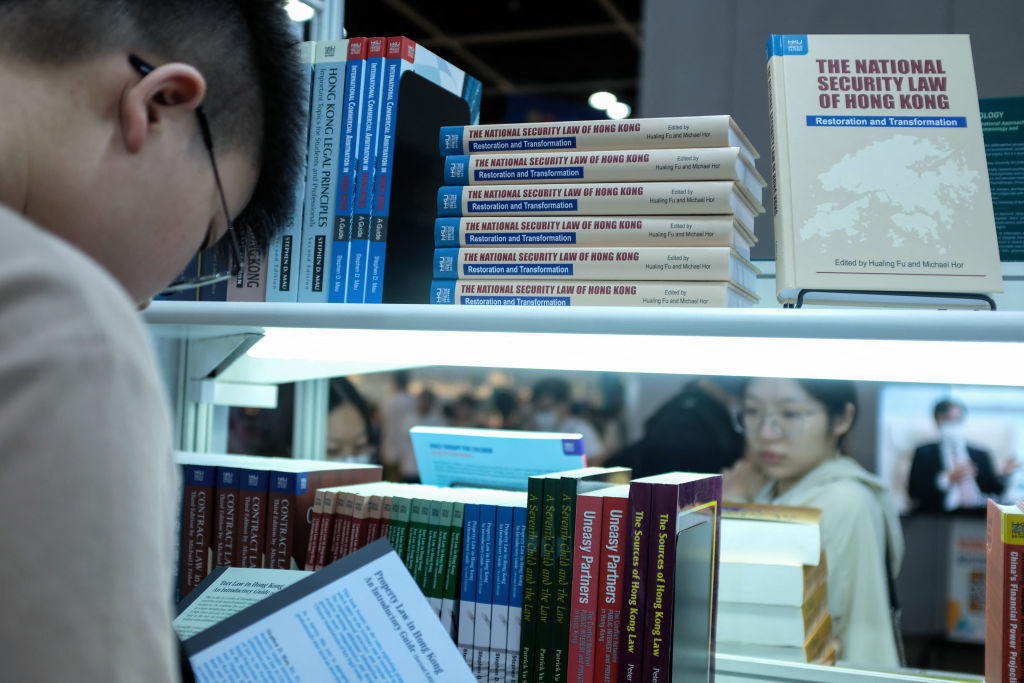

It’s the latest sign of waning freedoms in Hong Kong, since a sweeping national security law was passed in 2020 that has since been used to curtail civil liberties in the city and stamp out anything perceived as a critique of or threat to Beijing’s expanding influence in the former British colony-turned-Chinese enclave.

Andrew Lok Han Chan, the chair and founder of Societas Linguistica Hongkongensis (SLHK)—which formed in 2013 and has advocated for the preservation of Cantonese or Guangdonghua, a language with origins in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong (formerly called Canton) and also widely used in Hong Kong and Macau—announced on Facebook on Monday that he was disbanding the group “effective immediately,” to “ensure the safety of my family and former members.”

Lok said that on Aug. 22, officers from Hong Kong’s national security department visited his former home and entered without a warrant. Lok was not there, but the officers allegedly asked his family to relay a demand to remove an entry published online in an essay writing competition in 2020.

Lok, who is in Australia, tells TIME the essay that police asked to be taken down was “Our Time” by Siu Gaa, which imagines Hong Kong in 2050 after a government crackdown on linguistic and ethnic minorities as well as freedom of religion in the city. (Without providing any other information, Hong Kong police told TIME in a statement after publication of this article: “In conducting any operation, Police will act on the basis of actual circumstances and according to the law.”)

“We've thought we can have freedom of speech or freedom of art inside the competition,” Lok says. “They were just writing fiction. So we thought they were OK. But now you see, even writing fiction is forbidden.”

How speaking Cantonese became a political act

As the city’s lingua franca, Cantonese has earned a reputation of helping maintain Hong Kong’s identity, and by extension, autonomy from Chinese rule. But the notion of Hong Kong’s independence is a sore spot for the Chinese Communist Party, and with the passage of the national security law, promoting it is now sometimes a criminal offense.

Since the British handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997, the rise in popular use of Mandarin or Putonghua—the “common tongue”—in the city was not particularly political in nature, says Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London. The number of Hongkongers speaking Mandarin has drastically increased in recent decades, from 65,892 in 1996, the year before the handover, to 94,399 in 2011, to 165,451 in 2021, according to census data.

Under Xi Jinping’s rule, as China has increasingly repressed Hong Kong’s freedoms and identity, Tsang says, Hongkongers have viewed identifying with Cantonese as a means to push back. The SLHK’s shutdown falls in line with Xi’s other measures to increase the city’s swift integration with China, Tsang adds: “Dissent that can be seen as posing any kind of challenge to the CCP’s authority is no longer permitted in Hong Kong."

It’s not the first time the Cantonese language has become a political flashpoint between Beijing and Hong Kong. In 2016, the dystopian film “Ten Years”—which depicted a Hong Kong that has Mandarin as the dominant language—was reportedly banned from Chinese public screenings at Beijing’s behest. And in October 2022, China’s short-video platform Douyin pulled the plug on livestreamers using Cantonese for using “unrecognizable language.”

China has been, for years, trying to standardize language use across its various regions and territories to galvanize a uniform national identity. But that has come at the expense of other languages, and in turn, their cultures. In the western region of Xinjiang, officials have banned the use of Uighur in schools since 2017 in favor of Mandarin. In September 2020, residents of Inner Mongolia protested over a curriculum reform that changed the language of instruction in schools from Mongolian to Mandarin. And in June 2021, Sichuan provincial authorities closed down private Tibetan schools offering classes taught in the Tibetan language so that the learners will be forced to practice Putonghua, Radio Free Asia reported.

Read More: How Beijing Is Redefining What It Means to Be Chinese, from Xinjiang to Inner Mongolia

Lok says Hong Kong risks losing its unique character and independent cultural capital with further clampdowns on the Cantonese language and its advocate groups. “We have a huge cultural industry related to Cantonese,” Lok says, referring to Cantopop and the Cantonese film industry, which have earned global recognition. “The diminishing of the freedom of speech can also give a negative impact to the development of Cantonese culture.”

But Chaak-ming Lau, an assistant professor of linguistics at the Education University of Hong Kong, believes that despite increased use of Mandarin in Hong Kong society, the city is not at risk of losing Cantonese. In Hong Kong’s 2021 census, over 6.3 million people aged 5 and up still have Cantonese as their usual spoken language. The Hong Kong government’s official stance is promoting biliteracy in English and written Chinese, and trilingualism in English, Putonghua, and Cantonese. And in the Ethnologue, the world’s most comprehensive catalog of languages, Cantonese—as part of the Yue Chinese family—has “institutional vitality,” which means communities and institutions use it extensively. “Cantonese is very far from being endangered,” Lau tells TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com