In her 1892 masterpiece, A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South, scholar Anna Julia Cooper wrote, “Only the Black woman can say when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.”

Just a generation removed from slavery, Cooper—who is often called “the Mother of Black Feminism”—understood that the progress of African Americans, and of American civilization, is impossible without Black women. Only when Black women are no longer denigrated and diminished, but rather are truly elevated by all in society to their rightful status of equal dignity and divinity—and lives freely and fully as all men and women—can the Black race (and all human race) flourish to its fullest potential. For as long as Black women are devalued and delegitimized, so too will humanity.

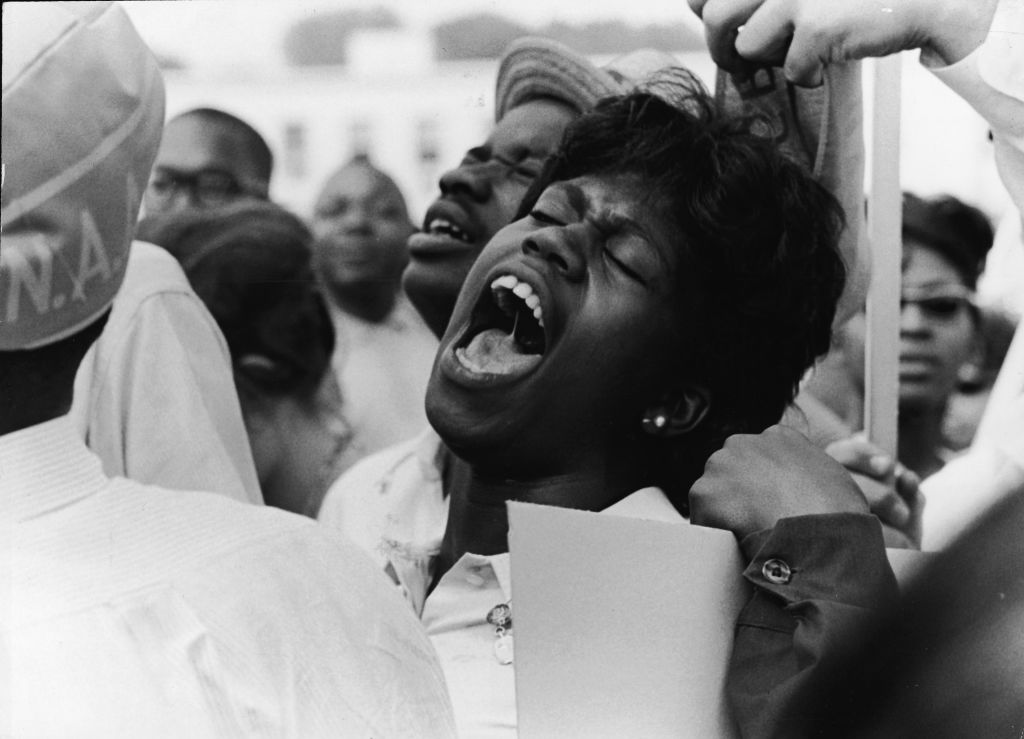

Cooper’s words still ring true today. 131 years ago, President Abraham Lincoln promised all Black Americans the right to live peacefully and be justly paid for their labor. In 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and other civil rights leaders marched hundreds of thousands of Americans to the nation’s Capitol, demanding America make good on that promise. Yet 60 years later, Black women remain disproportionately undervalued and mistreated by persisting racism and sexism—their families bearing the heaviest burdens.

In the 1960s, the historic practice of discounting women’s contributions to the workplace was perpetuated by a predominantly male labor force that especially undercounted work performed by non-white women. Work opportunities for women of color were scarce. The only jobs available to them were domestic labor-related, the lowest paid occupation type in 1963.

Read More: Experience The March on Washington in Virtual Reality

Today, while no longer restricted solely to domestic labor, Black and Brown women remain significantly segregated in the labor force: severely underrepresented in professions that typically pay more and overly represented in occupations with lower average salaries. The latter of these jobs—roles such as childcare workers, social workers, and substance abuse counselors—are critical to a healthy and functioning society, yet their wages don’t even begin to cover basic living expenses. According to the July 2023 Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies (FPWA) report, Black women’s work garners an average wage of just $30,789; for Latinas, a measly $23,196. In New York City, one of the most expensive cities in the world, over 44,000 women of color are contracted full-time human services workers. Roughly two-thirds of these workers earned below the city’s near-poverty threshold in 2019 and made 20-35% less in median annual wages and benefits than workers in comparable positions in the public and private sector.

More From TIME

These disparities extend to education. Even with comparable or identical college degrees, a Black person makes an average 20% less in wages each year than a white person. For Black women, the pay gap is even more stark. As noted in a report by compensation data and software company PayScale, Black women are the highest educated group, yet only with a master’s degree does she begin to earn more than a white man with an associate degree. It’s a tragic fact that Black woman must earn three times as many degrees as a white man to earn the same pay, let alone aim for slightly more.

While earning her degrees, a Black woman also often incurs more debt. Systemic racism has restricted Black families’ ability to grow assets and pass on generational wealth, leaving the average Black student to graduate with $25,000 more student loan debt than the typical white student. Pay inequities upon entering the workforce exacerbate this inequality. Recent 2023 data from the FPWA shows that four years after graduation, 48% of Black students owe an average of 12.5% more than they borrowed. On the other hand, 83% of White students owe 12% less than they borrowed.

Occupation segregation, wage deprivation, and debt accumulation hit the Black community hard. Coupled with enduring discriminatory laws, policies, and practices that all but ensure the over-policing and mass incarceration of Black men, the absence of these men and their potential earnings from the household is keenly felt by their families and communities.

Today, over half of all Black children live in households, where Black women are the sole breadwinners, compared to less than 17% of white children. These Black children often depend on only one income, which is frequently insufficient to cover all household expenses. As if on autopilot, the cycle of poverty repeats itself: lower wages and student loan debt plus the higher likelihood of living on a single income result in persisting income and wealth inequity, reinforcing poverty from childhood until the end of life. We see this devastating loop play out among today’s youth: One in three Black children live in poverty, in contrast to less than one in ten white children.

Despite centuries of having their worth diminished, Black women have boldly and unapologetically led and contributed to the development and progress of America. From reformers like Mary Ann Shadd Cary and Mary Church Terrell leading the early universal suffrage movement, advocating for the 15th and 19th Amendments, all the while being excluded from both Black men’s and white women’s suffrage movements, to Black women today such as Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, whose work as a immunologist led to the development of the vaccine to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and end the global pandemic. Denying Black women’s worth robs not just their families but the nation.

Decades-long practices of devaluing Black women, their work, and their worth reveal both the intent and the impact of structural and institutional racism exacted upon them. This pattern signifies the ever-growing threat to the Black community. Further, it signals the urgency to continue marching and taking actions to demand fairness and justice. If Black women were awarded the value they deserve, the entire nation would take an instrumental step forward in realizing its fullest potential.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com