Guatemala has long been a bellwether for Latin America. There was 1944, the year Guatemalans ousted a military dictator, beginning a democratization wave across Latin America; 1954, the year the CIA helped depose Guatemala’s democratically elected government, paving the way for the first of many Cold War era military coups; and 2015, when mass anti-corruption protests dubbed “the Guatemalan Spring” pushed a corrupt President and Vice President to resign, prefacing a wave of similar anti-graft demonstrations across Latin America.

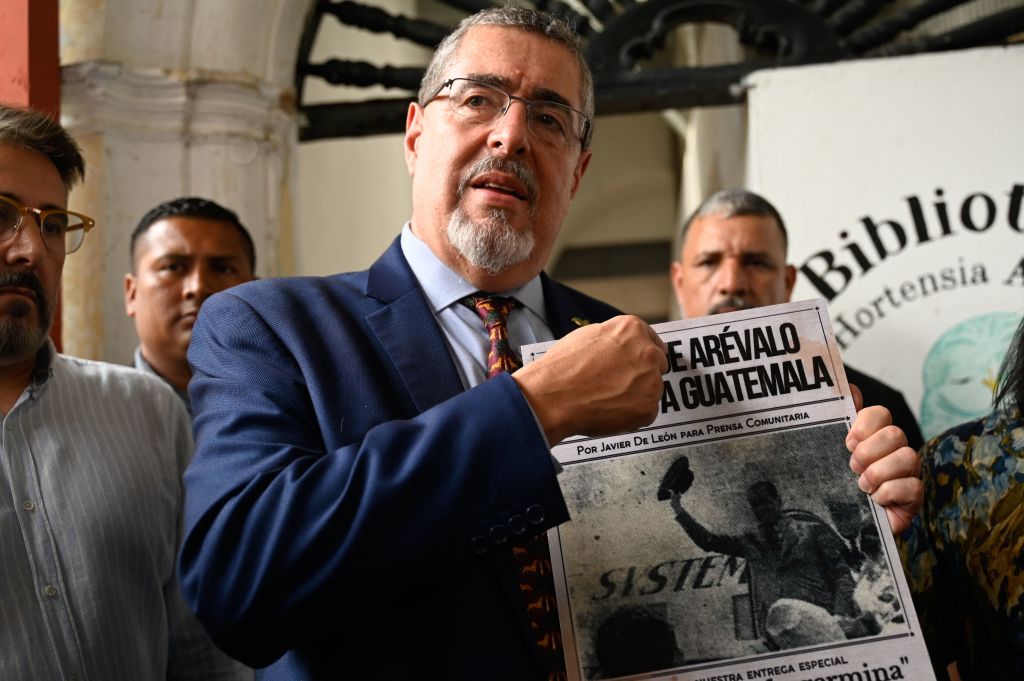

Now, Guatemala might once again play that bellwether role, as voters head to the polls for a crucial runoff election on Aug. 20 that pits the anti-corruption campaigner Bernardo Arévalo against the establishment-backed Sandra Torres. Arévalo, the son of Guatemala’s first democratically elected President, has strong reformist credentials and leads Torres in the polls by nearly 30 percentage points.

The centrist Arévalo and his Semilla (Seed Movement) party’s main pitch is to tackle Guatemala’s notorious corruption and beleaguered state institutions—the root causes, in their view, of the violence and poverty that have propelled many of the 3 million Guatemalans living in the U.S. to abandon their home country.

Read More: Guatemala Rethinks the Economics of Migration

“Guatemala can be a viable country, but it needs public institutions that resolve problems rather than creating them,” Jonathan Menkos, a congressman-elect from Semilla, told me. Guatemalan politicians have historically used kickbacks to grease the wheel. But Semilla’s members of Congress, most of whom are in their twenties and thirties, cut their teeth in politics by participating in the Guatemalan Spring. They promise no more vote-buying in Congress, skimming off the top of public contracts, or giving cabinet positions to power brokers in return for political support. They also pledge to pass an antitrust law—Guatemala is the only Central American country without one—to bust up the country’s monopolies and give small- and medium-sized businesses a chance. Boosting the quality of education and lowering healthcare costs are other big priorities.

Yet it’s Arévalo’s style of campaigning, as much as his policy agenda, that has earned him his surge in support among the urban middle class, millennials, and Gen Z, the latter two of which make up 6 in 10 Guatemalans. Arévalo and his team travel in their own cars and run their campaign out of a small rented garage-space in an industrial zone of Guatemala City. That separates Arévalo from traditional politicians who roll out big-budget campaigns.

Guatemala’s powerful political class has come out swinging against Arévalo. Attorney General Consuelo Porras—sanctioned by the U.S. State Department for “repeatedly obstruct(ing) and undermin(ing) anticorruption investigations in Guatemala to protect her political allies”—has brought legal cases that could block Semilla from leadership positions in Congress and lead to the arrest and imprisonment of several party leaders, half a dozen legal experts told me in Guatemala City. Prosecutors allege that party leaders falsified signatures used to register Semilla as a political party in 2019. But the move has prompted blowback from heavyweights in the Guatemalan private sector, as well as some key decision-makers in the courts, who granted an injunction in favor of Semilla. In a rare display of unity, the U.S., E.U., and the Organization of American States also loudly denounced the criminal cases against Semilla as election “interference.” The criminal cases against Semilla remain open; the Prosecutor’s Office has promised to push on after election day—as well as to open new investigations against Guatemalans who volunteer to help run polling stations.

For her part, Torres, who has allied herself with much of the political class, has sought to portray Arévalo as a radical leftist in disguise, intent on expropriating private property and foisting gender ideology and gay marriage on a reluctant, conservative society. A leaked video saw members of Torres’ National Unity of Hope party discuss overturning results at polling centers, and Torres herself has already cried fraud. Some speculate that the Prosecutor’s Office will imminently round up and arrest Semilla leaders.

If Arévalo does manage to come out on top on Aug. 20, and the election results are respected, that will be the beginning of the battle for Arévalo and Semilla, not the end. With just 23 of a total 160 members of Congress and next-to-no viable coalition partners, governing will be immensely difficult.

But at Arévalo’s closing campaign rally on Aug. 16—which drew the largest crowd the country has seen since the Guatemalan Spring—the mood was undeniably, unequivocally, hopeful. Grandparents held aloft pictures of democratic political heroes—among them, Arévalo’s father—from years past. As Arévalo took the stage, and the crowd roared, it felt like for all the recent reversals, Guatemala might once again be moving forward.

Much is at stake, but if Arévalo and his party win and manage to govern, against immense odds, they might just be able to turn Guatemala from a cautionary tale into a Latin American example of forward-looking change.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com