For nearly three months, the Indian state of Manipur had been raked with bloody violence between the majority Hindu Meitei and predominantly Christian Kuki-Zo tribes. But when a shocking 26-second video—which showed armed Meitei men stripping two Kuki women and parading them naked through the streets of Kangpokpi district—went viral in mid-July, the crisis sparked international condemnation and finally broke the Indian government’s silence.

The criticism grew after police records showed the incident occurred on May 4, raising questions over why the video only surfaced 78 days later.

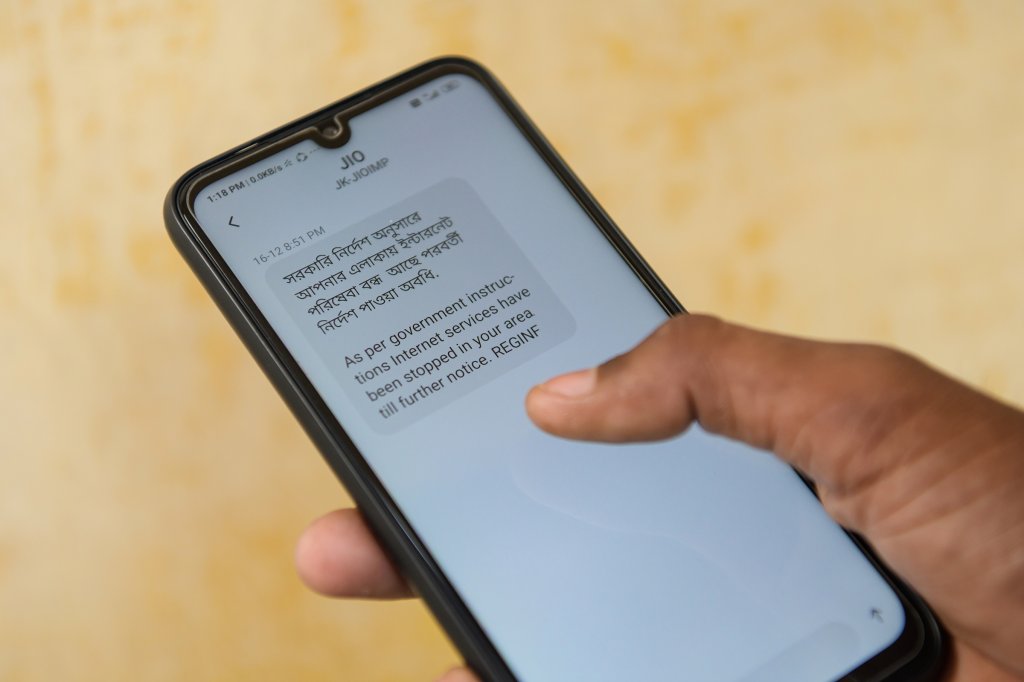

The answer, experts tell TIME, is that the authorities shut off the internet in Manipur on May 3. The state government, led by the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), says it did so to curb rumors and disinformation and quell the violence. But digital rights activists say there is no evidence that turning the internet off helped keep anyone safe—and that the move may have even fueled violence.

“The Manipur shutdown crippled the ability for information to reach the rest of the world,” says Mishi Choudhary, an Indian technology lawyer based in the U.S. who founded the Software Freedom Law Center, or SFLC.in, to fight for digital rights back home. “If we had seen the videos hidden from us for almost 80 days back in May, we could have reacted to it sooner.”

While the internet shutdown in Manipur may be one of India’s longest shutdowns yet, it is hardly unprecedented. “By and far, India is the most brutal censor of the internet in the democratic world,” says Choudhary.

India has ranked first in the world for shutting off the internet over the past five years, according to SFLC.in and other digital rights watchdogs. In the first six months of this year, it imposed almost as many shutdowns as it did in all of 2022, according to Surfshark, a Netherlands-based virtual private network (VPN) provider.

In addition to cutting off the internet, the government also routinely blocks specific websites or successfully pushes social media platforms to block content in India. Last year, that included nearly 7,000 posts and social media accounts, according to the nonprofit Access Now.

In Manipur, the government’s first course of action after the viral video triggered global outrage was to ask Twitter and other social media platforms to take it down because it could “further disrupt the law and order situation in the state,” a senior government official told The Indian Express on July 21. Four days later, Manipur’s high court intervened to direct the government to restore the internet, but in a “limited fashion.”

This means that social media websites, WiFi hotspots, VPNs, and mobile internet—used by the vast majority of Manipur’s 2.2 million people—remain blocked. The Internet Freedom Foundation in New Delhi has called this “illegal” and a deprivation “of basic human rights.”

As Manipur entered its 100th day of an internet shutdown on Friday, a far broader debate has emerged across India about the use of shutdowns, whether they work, and what social and economic costs they bring on.

The current era of total internet shutdowns began in India on Aug. 5, 2019, when the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir entered what would eventually be the world’s longest internet shutdown—lasting 552 days—which the Indian government imposed after controversially revoking the state’s constitutional autonomy. Authorities eventually reinstated 4G mobile services in 2020, after the Supreme Court determined the ban could not be indefinite.

Although internet access had been restricted around the country before, Kashmir was a “complete communications blockade,” says Choudhary.

Since then, the Indian government has imposed total shutdowns in many cases of communal unrest or public protests occurring across the country. To date, India has experienced a whopping 752 shutdowns since 2012, SFLC.in estimates.

The Indian government has not released a detailed accounting of the use of shutdowns. In July, Minister of Electronics and Information Technology Rajeev Chandrasekhar said the government does not maintain “centralized data” on the number of shutdowns imposed in India, and added that there was “no report available” to assess the economic loss. (Chandrasekhar was not available for comment.)

India had no laws to regulate Internet shutdowns until 2017, when the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 was amended to say that shutdowns could only be ordered by a state government’s home secretary when deemed “necessary” or “unavoidable” in public emergencies or in the interest of public safety. The amendments also dictate that a district magistrate, the administrative officer in charge in every state, must regulate shutdowns by clearly stating the rationale behind the decision in writing, which is then reviewed by a bureaucratic committee within three days.

But there is considerable latitude because terms like “public safety” and “public emergency” are not defined. In 2021, the internet was switched off when Indian farmers staged a months-long protest against new farm laws in the nation’s capital; in 2022, it was switched off in the city of Udaipur, in western India, when a Hindu tailor was murdered by a Muslim man in an incident that prompted fears over communal violence; and earlier this year, it was switched off once more when Punjab was placed under a three-day cellular blackout as police went on a manhunt to track down Amritpal Singh, a separatist Sikh leader on the run.

Sometimes the government implements shutdowns for seemingly mundane reasons—like preventing cheating in school exams or entry tests for competitive government jobs. A report by the Internet Freedom Foundation and Human Rights Watch found that almost a third of the disruptions counted from 2020 to 2022 were intended to prevent exam cheating.

The Supreme Court sought to toughen the rules against imposing shutdowns when it heard the case “Anuradha Bhasin versus the Union of India” regarding Kashmir. In a landmark verdict, the court prohibited the government from suspending the internet indefinitely and limited shutdowns to 15 days or less, providing a detailed set of guidelines to regulate such orders.

But the new guidelines did not prevent the shutdown in Manipur, which continues to be enforced through orders re-posted every few days. To SFLC.in’s Choudhary, the implications of this are clear. “Whether it's 78 days in Manipur or 552 days in Kashmir, internet shutdowns constitute a digital war in today’s India,” she says.

The impact of internet shutdowns is only growing as more and more people rely on an internet connection for their social and economic livelihoods.

In large part, that’s because India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, has for years pushed for a “Digital India” to transform the country’s economy and boost growth. India has built an extensive, public-facing digital infrastructure over time that includes a biometric identity system, a digital payment interface that allows payments through QR codes (and which now accounts for over 70% of all non-cash retail payments in India), and an online data management system containing IDs, tax documents, vaccine certificates, and more.

“On the one hand, the government pushes us all to live online, and on the other, it maintains a kill switch and uses it often,” Choudhary says. “And once you use that, you bring the entire economy and the entire social services to its knees.”

Top10VPN, a global digital privacy and research organization, estimates the overall cost of shutdowns in India was $184.3 million in 2022. The figure is likely an underestimate; it excludes the informal work sector and not every shutdown is reported. The cost estimate also masks the ways in which shutdowns affect specific communities, typically poor or marginalized ones. In Kashmir, for example, at least 500,000 people—mostly in the tourism sector—became unemployed as a result of the shutdown in 2019, according to a report by the Kashmir Chambers of Commerce and Industry.

And many experts say the shutdowns don’t work, even judging by the rationale the government uses for them. “What helps people keep safe in any crisis is the ability to access and exchange information,” says Namrata Maheshwari, who serves as Access Now’s Asia Pacific legal counsel, “and shutdowns can never be justified because they’re always inherently a disproportionate measure.”

They say that India’s situation is especially concerning given that in 2013 it joined many countries to proclaim, under Article 19 of the U.N.’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, that the right to freedom of expression and information “must also be protected online.” “There could not be a clearer basis for the illegitimacy of Internet shutdowns,” wrote Tanja Hollstein and Ben-Graham Jones, in an op-ed for the Westminster Foundation for Democracy.

Yet Indian authorities continue to double down on their approach. After the sexual assault video in Manipur garnered international headlines last month, the state’s chief minister, N. Biren Singh, said that “hundreds of similar cases have happened, that is why the internet is banned.”

For digital rights activists, not to mention the people in Manipur left in the darkness, such comments are dismaying. “When they say there are hundreds of crimes like the one we've already seen, then what is the point of all the shutdowns?” asks Choudhary.

—This story was supported by The Global Reporting Centre and The Citizens.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Astha Rajvanshi at astha.rajvanshi@time.com