On the surface, at least, the beef between Frederick Cook and Robert Peary was not political. Both men were turn-of-the century Arctic explorers, not presidential candidates, competing not for high office but for another coveted title: discoverer of the North Pole.

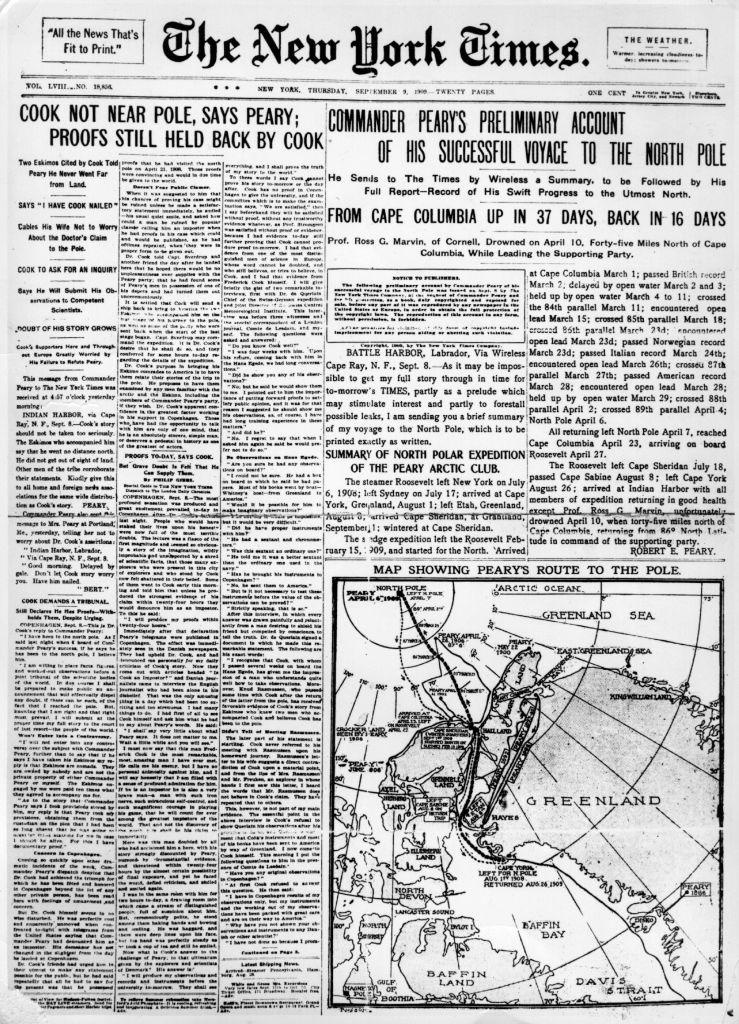

Their feud began in September 1909, when both men returned from Arctic journeys claiming to have reached the pole. Peary, the more famous of the two, publicly accused his rival of lying. The scandal that ensued was unprecedented in the history of exploring.

Though largely forgotten today, the Cook-Peary feud is worth revisiting for several reasons. It is an early example of America’s ongoing obsession with personality and publicity, and the extent to which these media-fueled distractions obstruct the search for truth. It also tells us more about Trump-era partisanship than you might expect; underlying the debate over sextant readings and sled dogs, scientific credibility and unsporting conduct, lay a hidden landscape of political and cultural divisions that is very much still with us.

The trouble began with the slippery nature of the goal itself. Unlike the South Pole, which occupies a fixed point on land—and was indisputably discovered two years later by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen—the North Pole is a notional destination situated atop drifting sea ice. Locating it using early 20th century technology was far more challenging than most people realized, and planting a flag to prove you’d been there was pointless, because anything left on the ice would simply float away.

Though explorers back then were generally taken at their word, scientific authorities also required them to provide a travel diary with daily mileage rates, astronomical observations, and other important records from their journey. Explorers were also expected to bring at least one eyewitness trained in the use of sextant and other scientific instruments, and to present this navigational equipment for examination afterward.

Cook and Peary shocked the exploring world by failing to provide corroborating evidence. For several months, what should have been a fairly straightforward discussion of ice conditions and compass bearings came to resemble a mudslinging modern political campaign, with each explorer striving to prove that he was a man of credibility and character.

Nearly everyone in America took sides. Looking back twelve years later, one New York City journalist likened the controversy to a great ideological schism. “In the promotion of domestic strife in every nation, in the setting of households against each other and bringing not peace, but a sword to every breakfast table, Cook and Peary did better than Lenin and Trotsky ever dreamed of doing,” he wrote.

Predictably, the press made a meal of the contretemps. The media loved a controversy back then as much as it does now, but the stark contrasts between Cook and Peary also made it easy for their interpersonal feud to tap into long-simmering national tensions. To an uncanny degree, each explorer represented different sides of an ongoing partisan divide.

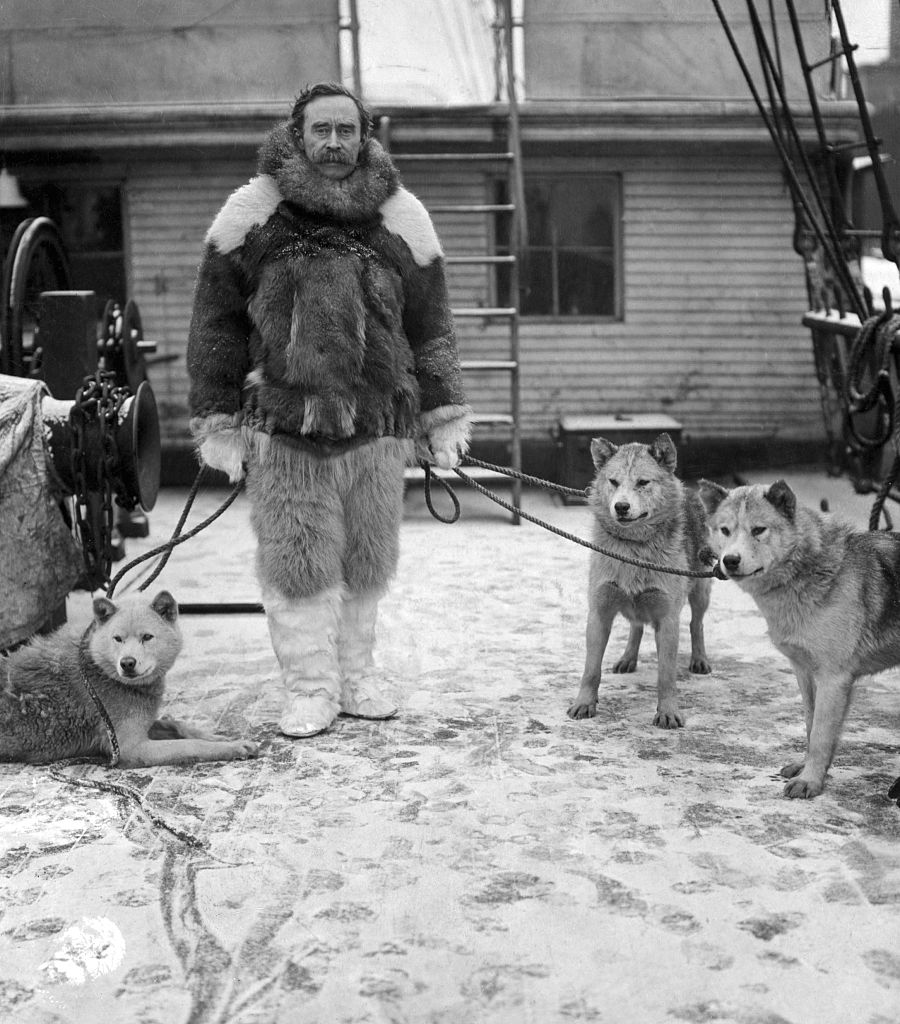

Peary, a U.S. Navy engineer based in Washington, was popular among the East Coast establishment. He was cozy with the National Geographic Society and the American Museum of Natural History, twin bastions of plutocrat-funded Gilded Age philanthropy, and bankrolled by The Peary Arctic Club, a coterie of mostly Republican New York City millionaires. Peary was as demanding and iron-willed as the rich businessmen who supported him. President Theodore Roosevelt (also a Republican) spoke glowingly of his “hardy virtue.”

For every American who admired Peary’s Yankee grit and self-discipline, however, there were many more who loathed him as a fur-clad embodiment of the corporate monopolist. The freewheeling Cook—who lacked Peary’s impressive résumé and social connections and was the son of German immigrants named Koch—was far more appealing to the average citizen.

Rather than rise through the naval hierarchy, Cook had carved his own eccentric career path.

He was the underdog going up against Peary’s “Arctic Trust”—a living, smiling symbol of the idea that anyone could make it. He won over the crowds with his warmth and humility, especially in the rural Southern and Midwestern regions that had cast electoral votes for the populist Democrat William Jennings Bryan.

Peary’s stronghold, by contrast, were the educated towns and cities of New England. The elite minority backing him included the respectable and pro-Wall Street New York Times, which filled many column-inches reminding its nearly 200,000 readers that Cook’s claim to the pole was based on his “bare word, no more, no less.”

But this caveat was lost on most Americans, who believed (according to newspaper polls conducted that fall) not only that Cook had reached the pole but that Peary hadn’t. Did the opinion of the average newspaper reader matter? The Times was at pains to remind its readers that it did not, and that the dispute would ultimately be resolved by scientific authorities.

Peary’s travel records and instruments were finally examined by the National Geographic Society in early November, nearly two months into the controversy. Its experts declared Peary’s claim valid, and pressure on Cook to present his own proofs intensified. Cook had embarked on a lucrative lecture tour by this point, fueling suspicions that America’s most popular explorer was a con man.

By the end of the year, those suspicions had hardened, and Cook was widely dismissed as a hoaxer. Though he maintained to his dying day (in 1940) that he’d discovered the North Pole, he went into hiding late that fall and lost all credibility within international scientific circles. The New York Times confidently dismissed him as “the greatest impostor of all time.” Peary was honored around the world, and generations of schoolchildren were taught that he was the pole’s discoverer.

Victory and validation for the establishment, then? Not exactly. The supposedly impartial Times—which had loaned $4,000 to Peary’s expedition in exchange for exclusive newspaper rights to his story—subjected Cook’s dubious claim to far more scrutiny than Peary’s, a display of favoritism that caused it to get half the story wrong. And a Congressional subcommittee concluded a year later that the National Geographic Society’s examination of Peary’s proofs had been “perfunctory and hasty” and its judges “prejudiced in his favor.”

But the official inquiry ended there, and before Peary’s death in 1920 and for many years afterward, institutional gatekeepers shielded his records from examination by unbiased experts. It would be nearly eight decades before the open-minded British polar explorer Wally Herbert was granted access to the family archives and discovered just how shaky Peary’s claim was. His findings made it clear that Peary had knowingly missed the pole and lied about it.

The Times in turn issued a remarkable correction in 1988, in which it admitted that neither Cook nor Peary’s claim was “untainted.” The discovery of the North Pole must then be credited to Roald Amundsen, who led a properly documented airship expedition there in 1926—an effort from which the National Geographic Society withheld its support, it should be noted, after Amundsen dared to question’s Peary polar claim.

What lessons does this sordid episode hold for today? One is that it can take a very long time for the truth to emerge. As Mark Twain famously said, “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes.” (Ironically enough, this quote itself is probably misattributed.) Another is that even in matters too complex for it to understand, the American public wants a say. That era’s American Minister in Copenhagen, who’d noncommittally squired Cook around the Danish capital after the explorer’s return from Greenland, found the North Pole Controversy eye-opening for this very reason. “I never before realized,” the diplomat later wrote, “how firmly my own people believed that the most important question may be settled by the vote of a majority.”

Ultimately, that was not the case, but nor did the masses dutifully come around in favor of Peary after Cook was exposed—and nor should they have, their mistrust of Peary’s powerful allies turns out to have been justified. He was not as egregious a liar as Cook, but he was still a liar.

The idealist will see the behavior of both explorers as equally shameful. But it’s also possible to view Peary’s lie—which he may have only embraced in response to Cook’s bigger lie—as slightly more excusable. It turns out that only the last 100 miles or so of his polar journey are in doubt, whereas Cook failed to prove that he took more than the equivalent of a few baby steps onto the frozen Arctic Ocean.

Cook had a showman’s talent for getting people to believe something because it made them feel good. Peary, for all his flaws, required a basic respect for plausibility and fact. He braced for combat that fall on false pretenses and for entirely selfish purposes, but he may well have spared America further embarrassment by helping to debunk Cook’s claim.

With a known con man who specializes in emotional satisfaction for his supporters likely to be a top contender for the White House in 2024, Cook’s polar hoax now seems less trivial than it might otherwise. He channeled popular sentiment into a wave, during a time of great economic and geographic inequality. And that sentiment was ripe for manipulation in large part because of the entrenched interests that Peary so neatly embodied.

Adapted from THE BATTLE OF INK AND ICE by Darrell Hartman, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Darrell Hartman.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com