Republican Rep. Anna Paulina Luna was on her way off the House floor on June 15 when she saw Mike Turner of Ohio headed her way. She steeled herself for a tough exchange. Less than 24 hours earlier, Turner and 19 other Republicans had blocked Luna’s resolution censuring California Democrat Adam Schiff, the MAGA-world villain who led Trump’s first impeachment. Undaunted, Luna had mobilized a backlash by right-wing firebrands Steve Bannon, Charlie Kirk, and an activist known as DC_Draino who labeled Turner and the other GOP dissenters the “Coward 20,” publishing their Congressional office phone numbers and triggering a wave of irate calls and social media harassment.

Turning to face the bulky ten-term veteran who chairs the House Intelligence Committee, a defiant Luna, 34, paused near the back doors of the House chamber. But as Turner started engaging her in discreet chitchat, it quickly became clear that he wasn’t picking a fight. He was looking to surrender. “We really want to censure Schiff,” Turner told the Florida freshman. “How can we work together?”

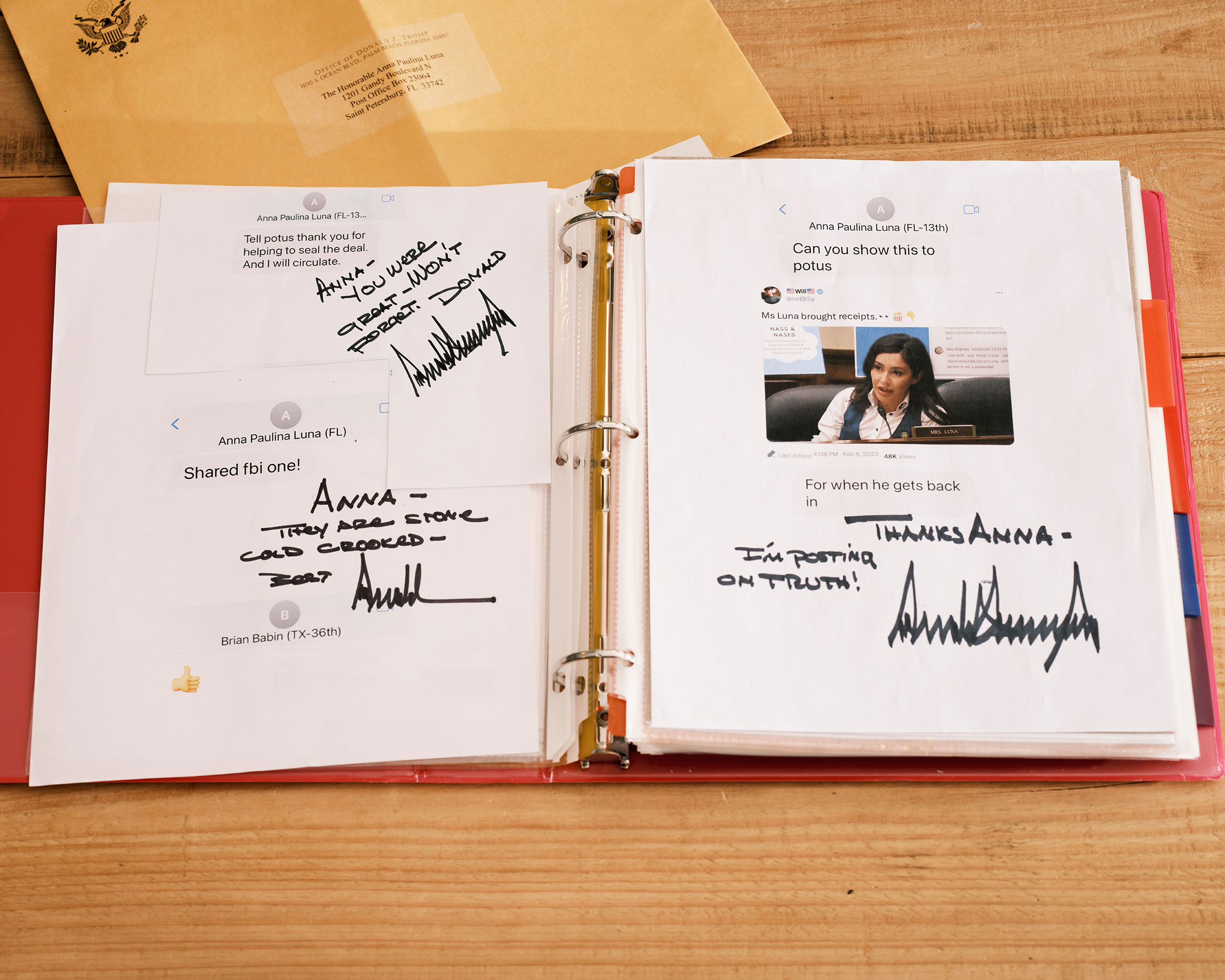

If Luna was surprised, she was also prepared, pulling from her purse a revised censure resolution that would force a House Ethics investigation into Schiff but that dropped an unprecedented $16 million fine. Sitting in her House office moments after the conversation with Turner, Luna exhibited a studied swagger. “I am telling you: I am persistent, and I am not kidding, censuring is going to happen.” Six days later, Luna forced another House vote to censure Schiff. This time, it passed 213-209. Not a single Republican voted against it.

The resolution was a milestone for Luna, marking her emergence from the mass of recently arrived GOP insurgents. To some, she’s a dangerously effective new version of the millennial MAGA politician ready to tear down the institutions of government in pursuit of an ultraconservative revolution. To others, she’s something more, the vanguard of a potentially significant turn in American politics. Luna is less a politician who parlayed her seat in Congress into a huge online following—like Marjorie Taylor Greene, Lauren Boebert, or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—than the other way around: the first social media influencer to parlay an online audience into a seat in Congress.

After a volatile upbringing, Luna got her start by cultivating a following as the director of Hispanic outreach for the conservative advocacy group Turning Point USA, where she worked under the tutelage of Kirk and his fellow instigator Candace Owens to learn the craft of provocative internet virality. Soon, she used her digital prowess to win a House seat in West Florida. Luna now has more followers on all social media platforms combined—more than 1.3 million—than any other GOP freshmen. And after only a few months in Washington, she has made it clear she’s on a mission to disrupt the governing class.

Whether that can result in substantive policy wins, or tangible benefits for her constituents, remains to be seen. Republicans hold only a slim House majority and remain thwarted by President Joe Biden’s veto. So far, Luna’s been mostly focused on the GOP-led investigations into the Biden Administration and Trump-style acts of retribution. Her adversaries deride her as a bomb thrower who cares more about creating a spectacle than passing legislation. “There are a number of members here who are just kind of ugly performance artists,” Schiff told reporters. “It’s all about getting attention.”

But even her critics recognize her potential to harness a new generation of crusading right-wing populists. Inside her office last month, wearing a bomber jacket over a white button-down shirt with a black tie, Luna spoke of the liberating power of using alternative media—the instrument through which she can both channel and ignite the base’s grievances—to circumvent the mainstream press. “A million impressions on a tweet is bigger than some primetime shows on network television,” she tells me. “When you’re a representative, and you can use social media as a tool, you essentially become the media.”

Luna’s path to a bully pulpit in Congress has been unlike anything Washington has seen. A five-month review of court records, conversations with nearly two dozen family members, colleagues, and friends, and more than five hours of exclusive on-the-record interviews with Luna herself, reveals a MAGA-inspired digital native whose hardscrabble life story and unorthodox resume has fueled a fast-rising political career. Now, she’s pushing the limits of the hard-right rebellion already upending power throughout the country.

“I don’t think she’s a conservative. I think conservatives are the reason we got here because they’re p—ies,” Bannon, Trump’s former chief White House strategist, tells me. “Anna Paulina Luna is the rise of populist nationalism. She’s at the forefront of that movement.”

Luna’s maternal grandmother was a heroin addict who died of complications related to HIV, according to her family and a death certificate provided by her mother. Her father had his own drug problem and on multiple occasions found himself inside of a jail cell. Luna, for her part, is a Trump-inspired Republican who, family members say, grew up on welfare and joined the military to pay for her education. And while Luna echoes other Republicans in opposing childrens’ access to gender transition treatments, she may be the only GOP lawmaker in Congress with a non-binary half-sibling.

“I don’t care what someone does as an adult,” Luna tells me. “Just leave the kids out of it and don’t force people to call you things they don’t agree with.” That position hasn’t hurt the tight-knit relationship she and her half-sibling both say transcends their ideological differences. “I don’t think we could be much further apart politically,” her sibling, Ricci Amitrano, tells me. “My relationship to her goes beyond this s–t. She’s the person who took care of me. She’s the person who made sure we were all okay. And I feel a duty to be that person in her life no matter what she believes.”

Luna’s singular biography helps to explain why she stands out in the conformist environs of Washington. She was born in 1989 in Southern California, where she grew up but rarely stayed in one place for long. Luna’s parents never married or lived together. On at least five different occasions, her half-Mexican, half-German father, George Mayerhofer, was sentenced to Orange County jail, according to records reviewed by TIME, on charges ranging from carrying a loaded firearm in public, probation violation, and driving on a suspended license. He also faced convictions for assault and battery and possession of a controlled substance.

When Luna was nine years old, her mother married a man with whom she had other children but divorced four years later. According to Monica Luna, her mother, the marriage was a toxic situation that brought further traumas on the children. At times, a young Anna would escape by spending periods with her father who, according to Amitrano, was often high, out of work, and in trouble with the law. “There was not a lot of stability for us,” recalls Amitrano. The family lived on government support, says Monica Luna, who moved throughout Orange and Los Angeles counties as her life kept making new turns—switching jobs, getting divorced, earning a degree.

Luna barely graduated high school, according to both her and her mother, because she changed schools so frequently. She obtained a high school diploma through an adult education program. One night at a party, she says, she overheard two young guys talking about college. When she asked how they paid for it, they told her they were in the Marine Corps. So the next day, she printed out directions from MapQuest and drove to a recruiting office, where she joined the Air Force on the spot.

After enlisting, she was stationed at bases throughout the country, according to Air Force records. One day, while stationed at Missouri’s Whiteman Air Force Base, she came across the Facebook profile of Andrew Gamberzky, a fellow enlisted member who was based in Florida’s panhandle. “I thought he was hot,” she says, “and I added him.” She eventually traveled to Florida to meet him in person. A month later, they got married. Luna was 20. “When you know,” she says, “you know.” Luna then asked to be transferred to her husband’s base, a request generally honored by the military to keep married service members together, and started taking courses at a local college.

As her adult life was set to launch, she returned to California in November 2013 to visit family. While there, Luna says she discovered her father living in a storage unit in the desert north of Los Angeles. He was hooked on crystal meth, according to both Luna and Mayerhofer’s longtime friend Lenny Ross. “He had a really bad drug problem, and he was bouncing around from place to place and then he actually became homeless,” Luna says. She wanted him to move to Florida, where she could look after him and get him into recovery. But knowing he was a man of pride, Luna says, she flipped the script to persuade him.

She told him that she needed his help in Florida because her husband was going to be deployed soon to Afghanistan. “I didn’t trick him,” she says. “I just more or less gave him a purpose and task.” It worked. After moving in with his daughter and son-in-law, Mayerhofer entered rehab and got a job stocking shelves at a Lowe’s hardware store, Luna says. Pretty soon, he met a woman he lived with and joined a local synagogue affiliated with Messianic Judaism, a quasi-branch of Evangelical Christianity that practices Jewish customs. Mayerhofer had converted to the faith in 2003, according to Ross.

But Luna’s life was soon beset by other complications. In 2014, Gamberzky was shot and wounded by enemy combatants in Afghanistan. When he returned home, he showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder; he was increasingly irritable and had trouble sleeping, Luna says. “I withdrew from my classes that semester, because I couldn’t go to school and deal with what was happening.” To support herself, Luna says she worked as a cocktail waitress at a gentlemen’s club and as a swimsuit model for Maxim Magazine and Sports Illustrated; she also appeared on Liberty Belles, a website that spotlights women in camouflage bikinis holding guns. “In that area, there wasn’t really a lot of opportunity, and, like, I needed to be able to take care of him,” she says. Gamberzky declined to be interviewed for this story. In a statement provided through Luna’s office, he said his wife “dropped everything to help me. We have seen so much together, and it only makes us stronger.”

By the next year, Luna was honorably discharged, Air Force records show. She transferred to the University of West Florida to major in biology, with the goal of going to medical school. But while at home taking care of her husband, Luna says she had a political awakening. She became increasingly animated by human trafficking at the border after discovering the story of Karla Jacinto, a victim turned activist. She joined the far-right nonprofit Operation Underground Railroad that conducts sting operations to expose child smuggling. According to her sibling Amitrano, the seed of Luna’s right-ward turn was planted in the Air Force. “My understanding is that she got indoctrinated when she joined the military,” they say. “People who are economically disadvantaged, their only option to go to school is to join the military, and the military kind of rams conservative rhetoric down their throat.”

Like many her age, Luna liked to vent on social media—except she went further than most. When she wasn’t posting gauzy selfies, she was pummeling the political establishment, particularly over immigration. Yet her screeds would get more attention than most others in the conservative ecosystem. “It was on Instagram that I first kind of cultivated a following.”

A critical component of her political posturing stemmed from her identity as a Hispanic American. Luna had spent most of her life until that point as Anna Paulina Mayerhofer, carrying the last name of her father. Her paternal grandfather immigrated from Germany, where he was obliged to serve in the Nazi Army as a teenager, according to Luna’s mother and Ross. After Luna married Gamberzky, she took her husband’s last name, but on social media went simply by Anna Paulina. The decision has led some critics to argue that she changed her name to advance her online presence. She formally changed her last name to Luna in 2019, both to honor her Hispanic heritage and her mother’s family, she and her mother say.

Either way, Luna’s identity as a Latina conservative with an obsessive focus on the border gave her an iconoclast’s platform from which to rise. “The apostate pose works best when people are already doubting and questioning their previous allegiance,” says the liberal political scientist Ruy Teixeira. “That’s why this stuff falls on receptive ears. People say, ‘Finally, someone’s saying what the f— is really going on here.’”

Something else would also soon pull her toward a more nationalist bent: the rise of Donald Trump. One day, in January 2016, she and her father attended a Trump rally in Pensacola, Luna recalls. “I agreed with his stance on sealing the porous border,” she says, “because I saw what was happening. That’s kind of when I started getting political.” After graduating from college in 2017, Luna re-enlisted in the military, serving in the National Guard while she studied for the MCATs. She was accepted into medical school at St. George’s University in Grenada. All was going as planned, until she caught the eye of one of the most powerful people in the conservative movement.

Part of Charlie Kirk’s job is to live on the internet. The pro-Trump activist and podcast host created Turning Point USA with the goal of creating an army of influencers to combat what he saw as the left-wing tilt on college campuses and in popular culture. One day in 2018, Kirk was struck by an Instagram video of a ferocious Latina immigration hawk. “It was literally a rant on how the news was full of it and they weren’t being transparent about what actually happens at the border,” Luna says. But the clip caught on like wildfire. “I saw that she was a natural talent from Day One,” Kirk says. He thought Luna had the same kind of magnetism he saw in Candace Owens, his first big discovery. “I realized she really had a spark.”

Kirk called Luna to offer her a job heading Turning Point’s Hispanic outreach operation. Luna was intrigued, but there was one problem. She was about to leave for medical school in Grenada. Kirk, a prodigious fundraiser, told her not to worry. He would reimburse her for the costs.

“That’s where I changed paths,” Luna says.

Luna was soon traveling with Kirk and Owens to campuses nationwide, orchestrating speaking events and trying to engineer viral moments by arguing with students. “We film our interactions with kids,” Kirk remembers explaining to Luna. “It’s really fun and unscripted and candid and can be dangerous at times.” Luna never flinched. She soon became a common presence in conservative media, where she relished the pushing of boundaries. In 2018, a Fox News anchor cut her off mid-interview after she compared Hillary Clinton to herpes: “She won’t go away.” In 2019, Luna spotted Kamala Harris, then a presidential candidate, in an airport. Sensing an opportunity, she asked a stranger to hold her iPhone and film her as she harassed the Senator over opposing Trump’s family separations policy. “That was, like, not planned,” Luna tells me. She says she believes in separating children and adults who cross the border together until a DNA test confirms they’re related: “That’s literally the way children are trafficked.”

It wasn’t long after that Luna decided to run for office herself. In September 2019, she launched a bid against Democratic Rep. Charlie Crist on Florida’s West Coast. She lost, but along the way she won a surprise seven-point victory in the GOP primary, and gained the attention of party bigwigs, like Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz. “We saw the way she used viral videos and hot takes on issues to get people to show up to rallies and events,” Gaetz says. Luna also showed she could raise serious cash, raking in more than $2 million on an average donation of $13. After the primary win, then-president Trump called to congratulate her while she was in a Chick-Fil-A drive-through. “We almost drove off without our food,” she says.

Two years later, Luna ran again for the same seat. This time, Crist was running for governor and the district was redrawn by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis to favor Republicans. But that second campaign would be marked by hardships beyond the rough-and-tumble of electoral politics. One night, in January 2022, Luna’s father was killed in a car crash. It was almost nine years since Luna had brought him to Florida and got him cleaned up. “He and I had enjoyed many years together where I was finally able to enjoy my dad,” she said. A few weeks later, she received a handwritten condolence letter from Trump, who signed it “Donald.”

With little time to grieve, Luna poured herself deeper into the campaign. More endorsements soon followed. She was one of the only candidates in 2022 to have the backing of both DeSantis and Trump, two men who are now bitter rivals. Luna would go on to defeat Democrat Eric Lynn, a former Obama administration official who outspent her twelve-to-one. She won by eight points.

In early January, just days after Kevin McCarthy won the Speaker’s gavel, he held a meeting with Rep. James Comer, the Kentucky Republican who was set to take over the high-profile House Oversight Committee. Comer was fielding requests for a spot on his panel—a coveted assignment among freshman Republicans looking for visibility. There was one in particular he wanted to run by McCarthy: Luna.

McCarthy had supported her primary opponent back in 2020, and Luna had more recently fought to block McCarthy’s ascent to the speakership. But he didn’t blink: Let her on. Luna was uniquely positioned, Comer says McCarthy realized, to help the GOP in the upcoming term, making inroads with younger voters, thanks in part to her online skills. “A lot of what we depend on members of the committee to do is messaging,” Comer tells me.

In a sense, that’s the whole ballgame for the GOP right now. With a Democratic president and Senate, House Republicans can’t do much beyond messaging. When her bid to censure Schiff initially failed, Luna showed her abilities in full. “Before I even got off the floor,” Luna says, “people were going ape s–t on social media because I’ve been talking about this.” But the episode also highlighted her ability to disrupt the party itself, exposing fault lines between the grassroots base and traditional Republicans they see as feckless and craven. Luna, with less than six months in Congress under her belt, proved an unlikely but effective catalyst. “I’m not trying to ratio these people,” Luna says of the Republicans like Ohio’s Mike Turner, who voted against her original measure. “My goal is just to hold this guy accountable, which needs to happen.”

Next up for Luna: Hunter Biden, Big Tech, and immigration. The Oversight Committee is now leading investigations into President Joe Biden’s troubled son, allegations that Twitter and other Big Tech firms have suppressed conservative speech, and the Administration’s handling of the southern border. She also introduced a bipartisan bill in March to combat sexual assault in the military. Luna, a House Freedom Caucus member, says her number one goal in Congress is to pass a law blocking the world’s most powerful communications platforms from having outsized control over content moderation. “If I get that done,” she tells me, “I could resign from Congress and be happy.”

That’s not going to happen anytime soon, given the balance of power in D.C. But over the long term, she and her supporters are hoping her brief tenure thus far is a prelude to more boundary-pushing conservative policy making. “We’re seeing this kind of new social-media phenomenon,” Kirk says. “Members of Congress are now more about moving the Overton window”—the spectrum of political and cultural ideas that a society will accept–“than advancing legislation. And I think she wants to do both.”

The first test of Luna’s staying power will come next year when she’s up for reelection. Her eight-point win in November, may have come in part thanks to the coattails of Ron DeSantis’ gubernatorial bid, says Rep. Jared Moskowitz, a freshman Democrat from South Florida who worked in the DeSantis administration and has a collegial relationship with Luna. Next time, Moskowitz says, she may face a different political landscape. “If she’s able to retain the district, then she’ll become a bigger star than she already is in the Republican Party,” he says. “No question.”

Luna is the fourth youngest member of Congress, the first Mexican-American representative from Florida, and the youngest House Republican. She is also currently the only one among her colleagues known to be pregnant, on track to give birth later this summer. In more ways than one, she represents a generational shift for a Republican Party that has traditionally been represented by old white men, and its turn toward rising populists whose views are formed more online than in the customary corridors of Washington power.

Luna says she will only spend as much time in D.C. as she absolutely must. She hotel-surfs whenever Congress is in session, and when I ask if she would consider ever getting her own place in D.C., she looks at me like I’m from Sweden. “You cannot pay me to live here full-time,” she says. “Absolutely not.”

But she doesn’t plan on leaving anytime soon, either. After the censure vote, dozens of Democrats huddled on the House floor shouting “Shame! Shame!” Shame!”—interrupting McCarthy as he read aloud the motion with Shiff standing feet away. The Speaker seemed to have lost control in a spectacle of Luna’s manufacturing, and she was making the most of it, live on social media, in a victory lap with her allies and fans. In real life, though, she had places to go: a Fox News hit from a studio van outside the Capitol and a fundraising dinner nearby. Before leaving the House floor, she stopped to deliver a message to her Democratic colleagues. “Don’t worry, guys,” she yelled across the aisle. “I’ll be here another two years.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com