During our own time of troubles, it is important to remember that in 1776 the men in powdered wigs who drew up the Declaration of Independence overcame political difficulties far more perilous than our own. Throughout the 1770s and 1780s, in fact, one wrong move in the Continental Congress might well have led to the secession of a regional bloc of states, whether New England, the Middle states, or the Southern states, with possibly cataclysmic consequences for all thirteen: continental civil war.

An apt metaphor capturing the spirit of the early republic is that of a shotgun wedding. If the New England, Middle, or Southern states had split apart into separate confederacies, civil wars would have broken out over finances, commerce, and, most of all, land. For this reason—the prevention of bloody mayhem—the founders reluctantly bound themselves into one Union. They united with the guns of civil war pointing at their backs, but, to their everlasting credit, they also practiced the art of cooperative political maneuvering in order to save the Union from self-destruction.

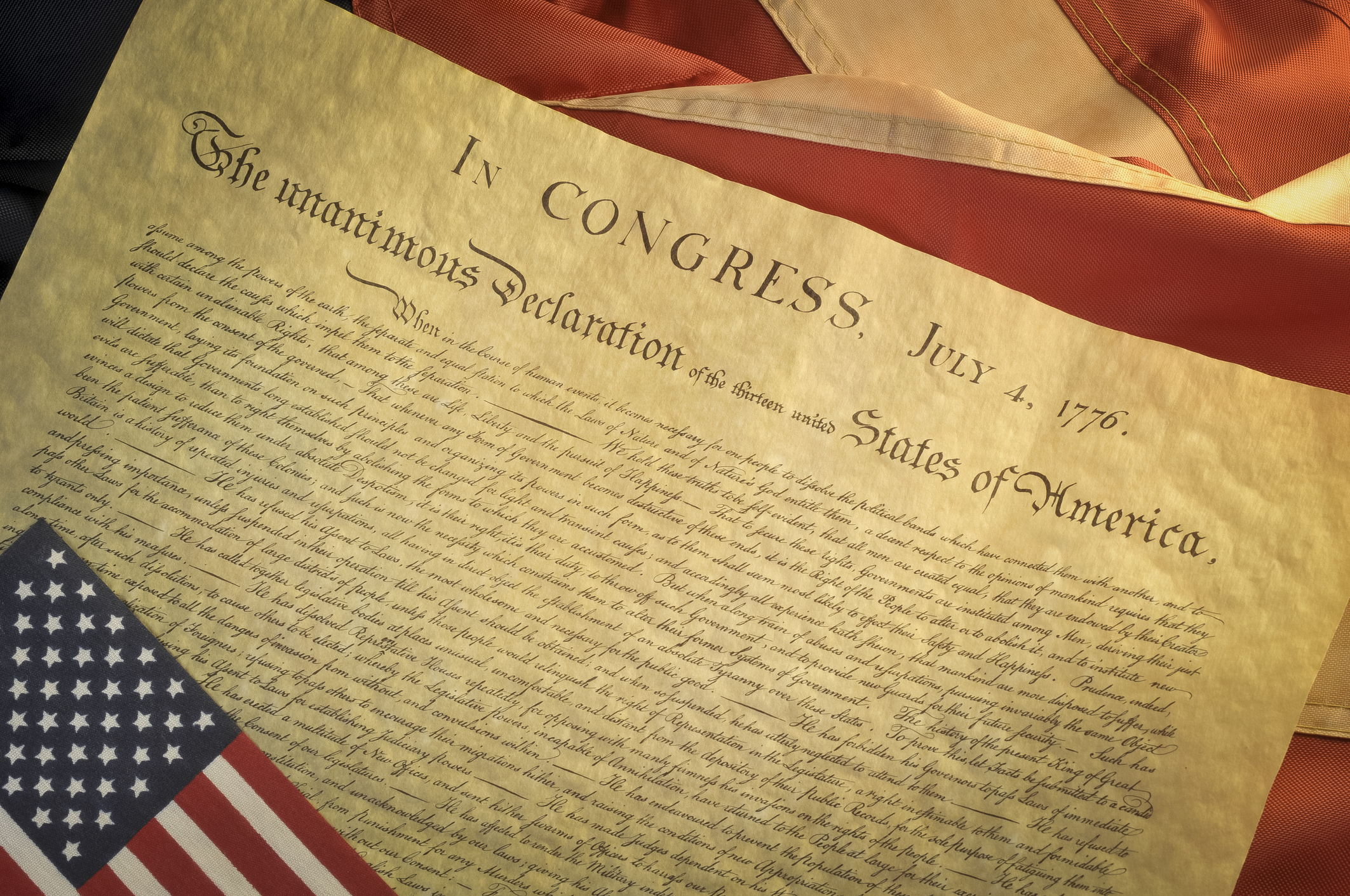

Consider early July 1776. American founding myth would have us believe that after years of British abuses and usurpations, the leaders of the thirteen colonies amiably adopted the “unanimous” Declaration of Independence.

In fact, the battle over the Declaration of Independence was an epic tale of secession threats, fears of intercolonial bloodshed, and furtive politics engineered to rescue the Middle states from tragically falling into civil war against New England and the Southern states.

More from TIME

Observers of the American scene had long since forecast that an independent America would self-destruct in civil wars. As James Otis, patriot and author of the influential “The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved,” averred in 1765, “Were these colonies left to themselves tomorrow, America would be a mere shambles of blood and confusion.” An English traveler visiting the colonies in 1759 and 1760 concurred, warning, “Were they left to themselves, there would soon be civil war from one end of the continent to the other.”

These were hardly isolated forebodings. After the British Parliament enacted the Coercive Acts in 1774 to punish Boston for its wreckage of more than 340 chests of tea in the harbor, newspapers were filled with anxious prognostications about the consequences of independence: American civil wars.

Read More: The Origins of the Declaration of Independence’s Most Famous Words

“Whenever the fatal period shall arrive,” Reverend Samuel Seabury of New York asserted that year, “in which the American colonies shall become independent on Great Britain, a horrid scene of war and bloodshed will immediately commence. The interests, the commerce of the different provinces will interfere: disputes about boundaries and limits will arise. There will be no supreme power to interpose; but the sword and bayonet must decide the dispute.”

Most of all, Seabury worried about the aggressive tendencies of the four tightly-bound New England colonies. In the event of independence, Seabury predicted, those colonies would “form one Republic,” and, as a result, “a state of continual war with New England, would be the inevitable fate of this province [New York], till submission on our part, or conquest on their part, put a period to the dispute.”

By this time, the founders had already witnessed firsthand the deadly centrifugal forces of disunion acting upon the Continental Congress. Most menacing, four of the five delegates from South Carolina had walked out of the First Congress in an act of nullification of the Continental Association, a proposed trade embargo against Britain that South Carolinians argued grossly disadvantaged their staple-crop economy far more than the diversified economies of the Northern colonies.

According to the South Carolina delegates, the nonexportation clause of the Continental Association, as written, overwhelmingly favored “the Northern Colonies” due to a combination of existing legal patterns of commerce, ship ownership, trade relationships, and those colonies’ expertise in smuggling. Therefore, they demanded a revision, exempting rice and indigo for the sake of the economic survival of their constituents.

When other delegates pushed back, the planters stiffened, declaring not only that they would not sign the embargo without this exemption but also that they would take their leave and return to South Carolina. To evidence their sincerity, they did actually stage a walkout. To prevent the break-up of the Union, the Congress compromised, yielding on rice but not on indigo.

As one South Carolinian delegate, John Rutledge, explained it, defense of their home colony’s economic interests motivated the walkout. The Continental Association, he argued, was biased in favor of the Northern colonies. And, he professed trenchantly, “he could never consent to our becoming dupes to the people of the North.”

By early 1776, the imperial situation had worsened considerably, forcing the question of independence upon the delegates with new urgency. Among other galvanizing events, Lord Dunmore in Virginia had issued an emancipation proclamation freeing all enslaved people who would join British forces, sending shock waves through the Southern states; King George III had declared all-out war on the colonies; and some New Englanders were contemplating the formation of a Northern confederacy because so many delegates from the Middle and Southern colonies continued to insist on reconciliation with Britain.

Primarily owing to the fact that New England soldiers were the ones dying on the front lines in the war with Britain, that region’s delegates in Congress were desperate to obtain a lifesaving military and naval alliance with France. And, as most everyone agreed, King Louis XVI was never going to ally with America until it first declared independence.

Therefore, numerous New England delegates began privately to consider forming a Northern confederation for the purpose of issuing a united declaration of independence. As Sam Adams of Massachusetts wrote to his cousin John Adams, referring to a conversation he had recently held with Benjamin Franklin, “We agreed that it must soon be brought on, & that if all the Colonies could not come into it, it had better be done by those of them that inclined to it. I told him that I would endeavor to unite the New England Colonies in confederating, if none of the rest would join in it. He approved of it, and said, if I succeeded, he would cast in his lot among us.”

In spite of the known risks of disunion, by June 8—the first day of formal debates on a resolution for independence for all thirteen states—representatives from the Middle colonies and South Carolina refused to go along. According to Thomas Jefferson, many of the delegates from those colonies drew a bright red line on the floor of the Continental Congress. “That if such a declaration should now be agreed to,” Jefferson recorded, “these delegates must (now) retire & possibly their colonies might secede from the Union: That such a secession would weaken us more than could be compensated by any foreign alliance.”

So tense and precarious were the battles over independence that the delegates shut down debates altogether, postponing further consideration until July 1, when they agreed they would cast definitive votes.

A letter written by South Carolinian Edward Rutledge in late June to fellow delegate John Jay of New York casts light on at least one American leader’s desperate fears of confederation and independence. Chiefly, Rutledge warned about the present and future dangers of New England dominating the American confederated government. Rutledge made explicit reference, too, the two means by which that region would exercise its oppression: military and naval might and power politics exploiting a weak constitution.

Bragging that he did not fear losing military engagements against New England, the South Carolinian did insist to Jay that entering into a single confederated government with that region of America was a dangerous proposition. “The force of their arms I hold exceeding cheap,” Rutledge declaimed, “but I confess I dread their overruling influence in council, I dread their low cunning, and those levelling principles which men without character and without fortune in general possess, which are so captivating to the lower class of mankind, and which will occasion such a fluctuation of property as to introduce the greatest disorder.”

Nevertheless, as scheduled, the delegates voted on independence on July 1, but before this they heard speeches. The most emotional and impassioned of them was delivered by Pennsylvanian John Dickinson, who begged the other delegates to reject independence. One reason he gave for this course of action was that if the thirteen colonies ever embarked upon a common path of independence the New England colonies would not long remain faithful to the American Union.

Looking into what he called the “Doomsday Book of America,” Dickinson conjectured that New England would break off from the rest within twenty or thirty years of a declaration of independence, making war on New York to gain control of the Hudson River, with unknown cascading consequences for all the colonies. This scenario of American civil war sparked at the Hudson River, he said, was too “dreadful” to contemplate.

Still, they voted on July 1, and the results were disastrous. Only nine states cast ballots for independence. Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted no. Delaware divided, rendering its vote null, and New York abstained, because it lacked permission either way.

This was a moment of extraordinary peril for the American Union because by now diehard New England and Virginia, for sure, had no intention of backing down on independence, and, as the vote evidenced, a supermajority of Congress (nine colonies) was ready to move immediately to a declaration. So, the delegates agreed to work overnight to break the impasse, revoting the matter of independence the following day.

We do not know what was said—or threatened—during the debates of July 1 or later that day and night. What is certain, however, is that the Middle colonies and South Carolina were left with a life-and-death decision to make. Were they going to engage as allies in a war with New England and the other pro-independence states—or against them.

Especially the Middle colonies, squeezed as they were geographically between the New England and Southern colonies, were caught in an impossible military situation. Doubtlessly, if they did not aid New England and the Southern colonies in their war effort, allowing free passage on roads and rivers, as well supplying their armies, chances were that Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New York would become the worst fields of blood on the continent in the expanding imperial civil war, now pitting American against American.

Therefore, for the sake of self-preservation, the Middle colonies and South Carolina chose the lesser of two evils. On July 2, under an injunction of “Join or Die,” they threw in their lot with the pro-independence colonies. On that day, twelve states voted for independence, with New York promising to assent to the resolution as soon as it received formal approval by its state legislature. It was indeed a shotgun wedding, one that created a nation.

The Continental Congress formally adopted the resolution for independence on July 2, catapulting the U.S. into an unpredictable future. Two days later, the delegates ratified the “unanimous” Declaration of Independence, dissolving all political bands with Britain and proclaiming to the world that “when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.”

As Delaware delegate Thomas McKean later recalled about the high-pressure, perilous days of early July, “Unanimity in the thirteen states, an all-important point on so great an occasion, was thus obtained. The dissension of a single state might have produced very dangerous consequences.”

The founders did it. They adopted the improbable Declaration of Independence. They formed a republic and won the war. And, in the Treaty of Paris, they successfully secured the entire trans-Appalachian West stretching to the Mississippi River, doubling the size of the nation.

George Washington, John Adams, James Madison, and the rest accomplished these stunning feats not only in spite of the tactical advantages of the British army and navy, but also in spite of the overwhelming centrifugal forces of disunion and civil wars that were acting on them every day.

That is one reason Adams predicted that the sacred day the thirteen states launched into independence “will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com