In Akalgarh, a village in the northern Indian state of Punjab, Jagdeep Kaur’s family cobbled together a hefty $8,500—almost four times the average annual salary in India—for a dowry to wed Sukhminder Singh. Kaur’s family also gifted gold, expensive clothes, and furniture during the wedding, which they used a loan to pay for. They hoped that by marrying Singh, a Non-Resident Indian (NRI) living in Hamburg, Germany, Kaur would have a better life abroad.

But the blissful union was never meant to be. A mere month into their marriage in 2009, Singh returned to Germany, where he had a job at a restaurant. He promised Kaur that he would soon get her paperwork done and bring her with him to Europe. That never happened, and Kaur, now 43, met Singh, also 43, only a few times during his subsequent trips back to India.

Kaur is still married to Singh and in 2017 she learned about her husband’s dark secret: not only did he have another wife in Germany, but two children. “I was shocked and didn’t know what to do,” Kaur tells TIME from her home in Ludhiana, swabbing tears from her face with her scarf. She has now filed cases at the Judicial Magistrate Court in Jagraon—a town around 25 miles from Ludhiana—against Singh and his family members in the area for cruelty, fraud, and cheating.

More from TIME

Kaur is one of thousands of wives who have been deceived by husbands living abroad, and hoping to get justice through India’s overburdened legal system. Though official statistics are hard to come by, a 2018 petition by eight such women in India’s Supreme Court said there are more than 40,000 wives who have been deceived into marrying NRI men. India’s government has dealt with more than 6,000 grievances against NRI men from 2015 to 2019.

Many Indian families hope an NRI son-in-law would provide better opportunities for their daughters. That has prompted some to spend exorbitant amounts on dowries to secure an NRI son-in-law, says Mamatha Raghuveer Achanta, founder of the Network Of International Legal Activists (NILA), a nonprofit that has assisted more than 250 women who have been deceived by NRI husbands. “They neglect to verify the credentials of the groom, resulting in many Indian women being abandoned by their husbands,” she says.

Reeta Kohli, a senior lawyer at the Punjab and Haryana High Court, says these women are virtually “bridal widows” and “do not live the life of a partner.” She adds that some even end up “working as maids at their in-laws’ homes while waiting for their husbands to return.” Kohli says these circumstances often lead to abuse or exploitation.

It’s a concern echoed by Vidya Ramachandran, a Ph.D. candidate at Oxford University researching women who have been abandoned by NRI husbands. She has interviewed over 30 women in the past six months and “a vast majority of these women allege experiencing abuse from their in-laws. In most of the cases, these women have been harassed for dowry,” she says.

Although dowries have been illegal in India since 1961, Achanta calls the legislation “toothless.” “There is no mechanism to monitor its implementation in the country to date,” she adds. Data suggests that dowries remain widespread—a 2021 World Bank study indicates that they continue to be paid in most marriages, with a bride’s family spending seven times more on average than a groom in the data that researchers studied—a fact that experts say is driving the issue of abandoned brides.

Satwinder Kaur Satti, 42, knows all too well the uphill battle for justice for abandoned brides. The Ludhiana native has for years been at the forefront in the fight against NRI husbands who have scammed their wives. A victim of a sham marriage herself, Satti not only fought against her NRI husband in court but led several protests in Punjab and New Delhi until she was granted a divorce by a local court in Ludhiana in August 2022, and then alimony.

Others are not quite as lucky. Beyond the stigma of being abandoned in a socially conservative country, these women struggle to find new partners, in part because they can’t remarry until a divorce is granted.

In 2016, during the course of Satti’s fight for justice, she founded the NGO Abandoned Brides by NRI Husbands International (ABBNHI) to help victims like her. She says that ABBNHI has helped hundreds of women across Punjab file cases against their husbands.

Women can file grievances under Section 498A of India’s penal code, which deals with cruelty toward a woman by her husband or his relatives, and can carry up to three years in jail and a fine. In cases of abuse, the women can also seek justice under the Protection of Women From Domestic Violence Act, to secure compensation and the right to live in their matrimonial home.

According to Kohli, local courts in India have in some cases ordered abandoned brides to be paid monthly assistance from husbands. But she and others say that actually receiving payment is rare. “When it comes to getting maintenance, or any sort of justice in such cases, it becomes a herculean task,” Kohil adds, citing lengthy court procedures and uncooperative police, not to mention the difficulty of jurisdictional issues that come with husbands who live abroad.

In most of the cases that Satti’s organization has handled, she says the passports of NRI husbands were revoked by Indian authorities. (If they don’t appear before a court despite being summoned, the court can declare them a “proclaimed offender” and revoke their passport. The court can also issue a “lookout circular” notice that can be used to bar them from entering or leaving India.) Satti says such an outcome often prompts NRI husbands to reach a settlement with their wives.

Experts have also called on the government to pass the Registration of Marriage of Non-Resident Indians Bill, which was introduced in parliament in February 2019 by India’s then-foreign minister, Sushma Swaraj. The bill would require all marriages involving NRIs to be registered with a local authority within 30 days and grant authorities the power to revoke passports if individuals fail to do so; it would also facilitate the seizure of property for any “proclaimed offenders” who fail to appear in court.

In March 2020, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on External Affairs approved the bill but called for amendments to make it “exhaustive” by registering more information from NRI men, including passport details and foreign addresses, among other measures. But in the three years since, the bill has yet to become law.

Back in Akalgarh, Kaur is still waiting for justice against her husband. In February 2020, Singh was declared by the magisterial court in Jagraon a “proclaimed offender” for his failure to appear in court for almost two years. Indian authorities also issued a lookout circular against him, meaning he can be arrested if he comes to India. His Indian passport has likewise been revoked, according to Kaur, who shared a copy of a letter from a local passport office over its decision to impound the document.

But Kaur has yet to receive the $8,500 her family paid in dowry, or any other compensation for her decade-plus ordeal. The Jagraon court in March 2020 ordered Singh to pay Kaur $123 in monthly financial support, but both she and her father say that hasn’t happened.

Kaur’s lawyer is now pushing for Singh’s family home in Mohie village, located in the west of Ludhiana, to be seized so it can bring him to the negotiating table. Kaur had lived in the house with her in-laws until 2017; she says she moved out that year after discovering photographs and documents in Singh’s suitcase—during one of his trips back to India—of his other family in Germany.

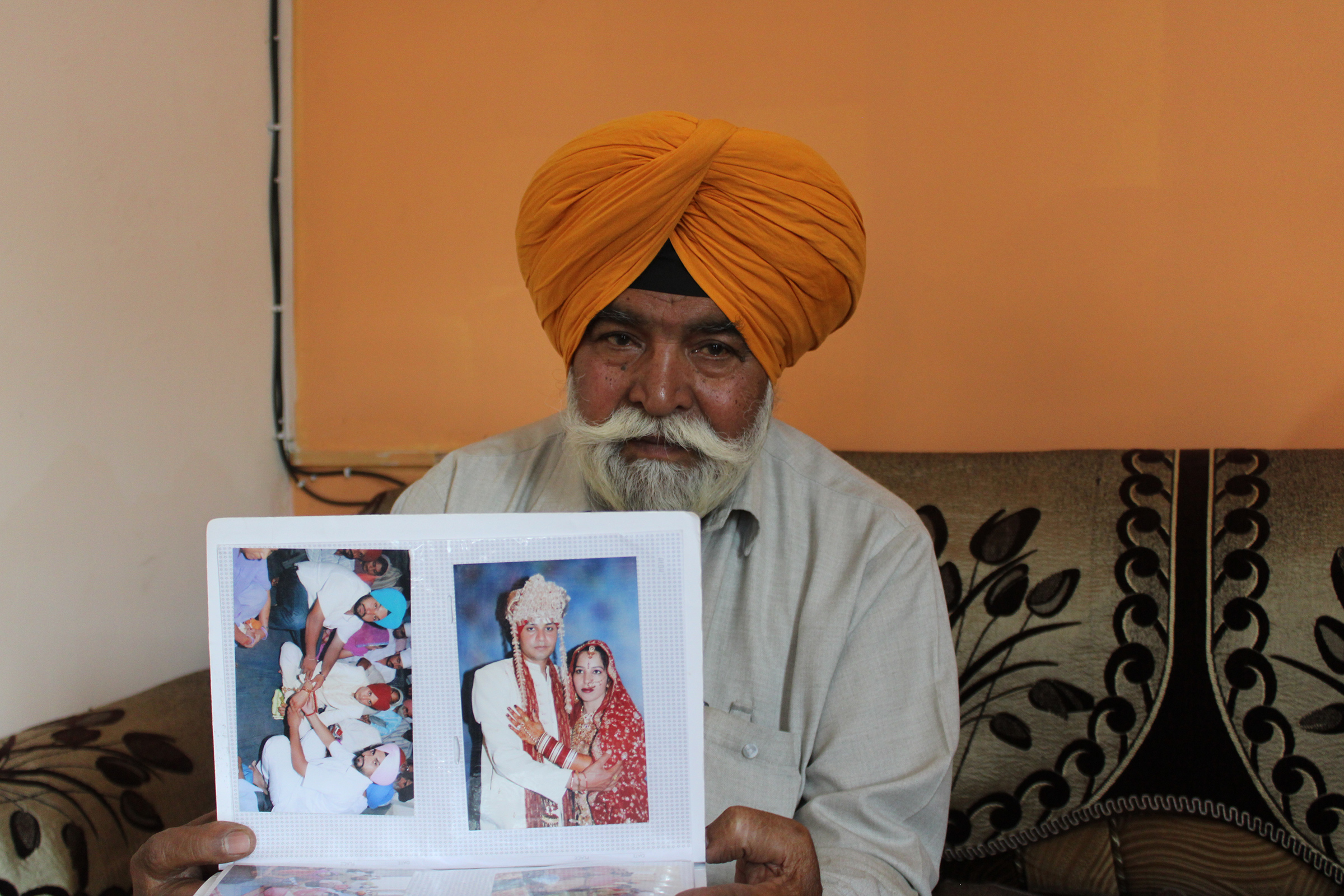

Since then, Kaur has been living with her parents. She now works as a tutor for children and earns a meagre $40 a month, or $480 a year—about one-fifth of India’s average salary of $2,250. Her father, Jit Singh, 71, a former officer in the Indian Air Force, provides her with considerable financial support, including the expenses of the court cases against Singh.

But old age and multiple ailments leaves Jit Singh worried about his daughter’s future. “What will happen to my daughter after my death? This thought is killing me inside,” he says.

It’s a fear that Kaur no doubt shares. “I’ve lost faith in everything now,” she says. “What I want is justice. I want him to pay me what I had given him and his family in dowry and compensation—so that I can live the rest of my life without being dependent on anyone.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com