Floridian Jeff VanderMeer is a New York Times-bestselling novelist whose articles have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Esquire, and The Nation.

Early in the 20th century, engineers blew up waterfalls and rapids in Miami rivers to clear the way for a canal. Wildcats scattered and fish floated to the surface, paralyzed. As legend has it, at least one alligator’s body went flying in the explosion, gawked at by local dignitaries.

Dynamite and dredging were the tools chosen to drain the Everglades and tame the waters. What once belonged to the Tequesta Native Americans, amid a wealth of wildlife, became parking lots and hotels owned by white people. Today, many of those parking lots are submerged during storms and, in some areas, the hotels overlook waters toxic with industrial and construction waste.

Florida is a bellwether for the rest of the nation; the surge water rise that besets Miami today will, soon enough, beset states ranging from California to New York. The state, of necessity, should be a leader in U.S. climate resiliency. But rather than acknowledge a crisis and build out a holistic approach to climate change, Florida, led by Governor Ron DeSantis, denies the urgency and applies a hodge-podge of contradictory initiatives designed for short-term applause. Some come with large amounts of money attached, while the state simultaneously ignores the peril of poorly regulated industrial-scale farming, ranching, and development that intensifies the crisis.

Ruinous policy in Florida affects 11 million acres of wetlands, thousands of lakes, more than 1,300 miles of coastline, and hundreds of freshwater springs. From rock pine to salt marsh, from sandhill scrub to lush semi-tropical ravines and dozens of other unique ecosystems—the point lost on DeSantis and the Republican legislature is that these are not tourist sights housed in an amusement park, but vital parts of the actual world that humans occupy and need to thrive, perhaps even to survive.

More from TIME

Yet, even as he pivots to a presidential run, DeSantis continues to downplay the risks of climate change.

Asked about hurricanes and climate change during a FOX News interview on May 24, DeSantis said he “rejects the politicization of the weather,” echoing his 2022 statement that “I can’t control the climate. I’m not doing mandates on any of that.”

That same day, the Sierra Club gave DeSantis an F for his environmental record, citing, in part, his attitude toward climate change and general “mismanagement.” Florida lags behind many states with decades-old energy efficiency guidelines while a recent DeSantis line-item budget veto disqualified Florida from receiving $346 million in federal funds from a program meant to improve energy efficiency across the country. DeSantis also signed legislation taking clean energy decisions away from local government; has yet to ban certain kinds of fracking; allowed exploratory oil drilling in the ecological sensitive Apalachicola River Basin; and, despite 2018 campaign promises, failed to lodge an objection to recent federal permits allowing drilling in the Gulf of Mexico.

Mismanagement, in this case, compromises the future of a state that has the fourth-largest economy in the U.S. and 14th largest economy in the world, just above Mexico. (In response to a detailed list of questions sent to the DeSantis team, a spokesperson did not respond directly to this or any other issue. Instead, they sent a list of monetary outlays for environmental issues made under the DeSantis administration.)

The stakes involved are not just the quality of life for Floridians, but actual lives—and the potential, as DeSantis exports his brand, that ecosystems nationwide will suffer from weakened regulation and be left for dead.

A coarsening of political ecosystems

If Florida’s wild places have evolved, with exceeding sophistication, to excel in a geographically fragile setting, then, in recent years, an opposite devolution has occurred politically in the human world.

When former governor Rick Scott took office in 2011, the state’s environmental regulation still supported some measure of sensible policy. But Scott had no vision for conservation, only an agenda beholden to aggressive business interests. This included dismantling good policy and banning use of the terms “global warming” and “climate change,” while stacking agencies, commissions, and departments with political appointees—many of whom lacked the qualifications necessary for the jobs, according to civil servants within state agencies who requested anonymity for fear of retribution—while forcing out scientists and other experts.

DeSantis, on paper, looks better than his predecessor, but he hasn’t rolled back Scott’s bad decisions. The Department of Economic Opportunity Scott created—to replace a Department of Community Affairs devoted to sensible citizen-responsive land management decisions—continues, now as the Department of Commerce, to divide up Florida into economic zones that often end up helping extractive industries or huge developers. DeSantis also has accelerated the practice of politicizing appointees, based on campaign donations, even as he gives lip service to environmental issues.

Recently, DeSantis announced billions of dollars for Everglades restoration, but the move may come with hidden political strings and calculations. Environmental analysts believe that some of the planned water projects may benefit large-scale agriculture more than the area’s habitat and biodiversity. It will take time to track how the money flows and where, and how much becomes trapped in eddies and swirls of bureaucracy or lines the pockets of DeSantis donors.

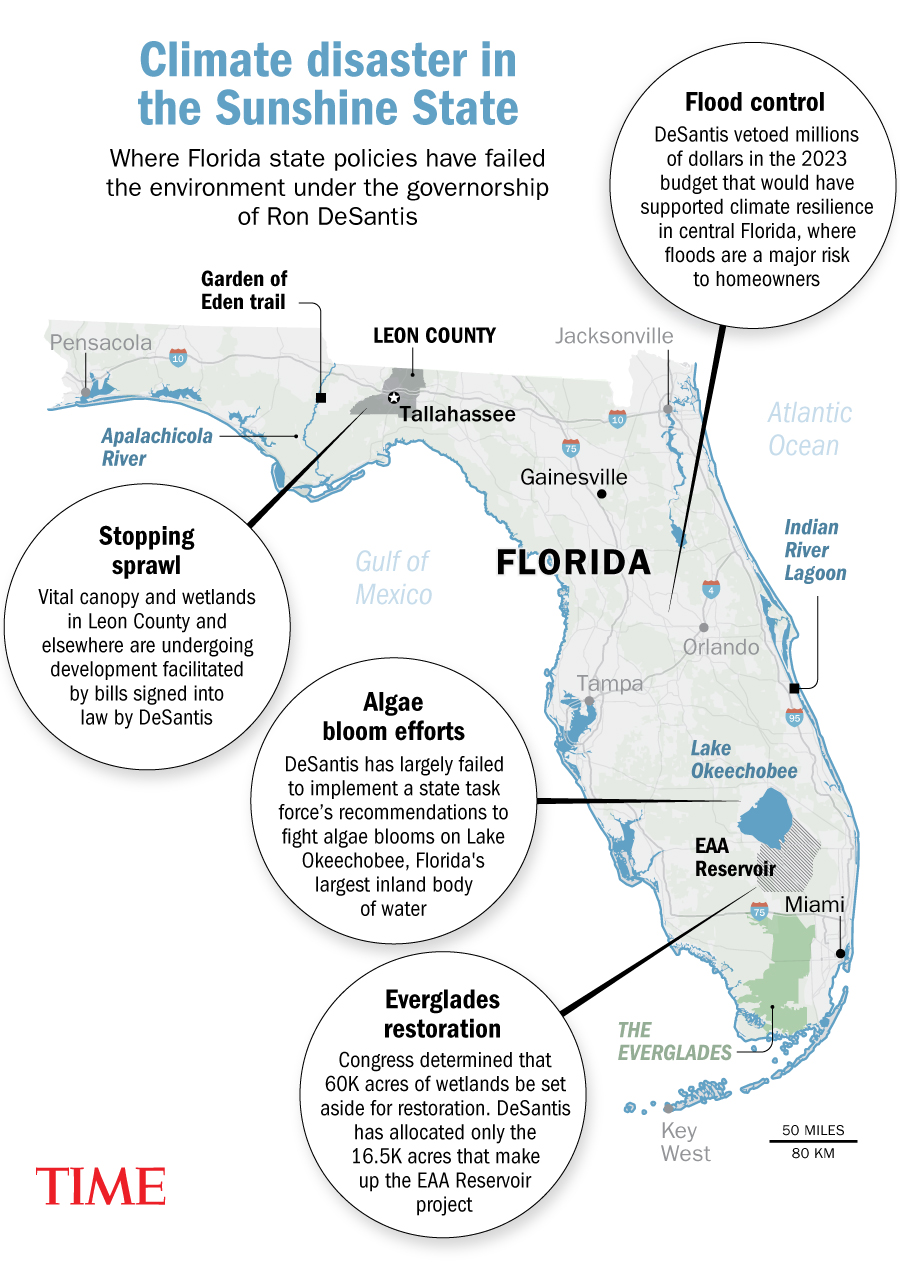

The projects DeSantis has greenlit often lack the scope to fulfill lofty promises. The governor’s “crown jewel” of Everglades restoration, the EAA Reservoir artificial wetlands project, allocates 16,500 acres for restoration—a pittance of the 60,000 acres stipulated in the Congressional Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan.

In the language of ecosystems, the reservoir has not evolved in a complex enough way to sustain itself over time. In the language of human policy, as Eve Samples, executive director of the Friends of the Everglades, notes, “Pumping record amounts of taxpayer money into earth-moving restoration projects will only be effective if these projects are properly scaled and designed to address Florida’s water-quality and water-quantity needs.”

Good policy requires an integrated plan, including adequate staffing. Natural ecosystems are self-sustaining because they come “fully staffed” with the organisms that keep them running. In the human world, staffing should occur as a core principle of project management, especially in projects with hundreds of millions of dollars behind them. But experts believe that the EAA Reservoir and other new projects may actually force existing state employees, already spread thin, to be pulled from maintenance of other essential projects.

For all of these reasons, there may not be an EAA Reservoir in a hundred years, even if rare ghost orchids still bloom in the area. This hasn’t stopped DeSantis from pointing to Everglades restoration as a reason to call him the “Teddy Roosevelt” of conservation—despite overruling a judge’s findings to support a Miami-Dade County highway extension that would encroach on important wetlands and endangered panther habitat. The loss of wetlands for projects like highways signifies the loss of sophistication and complexity in landscapes. A road means the poisoning of surrounding groundwater by toxins from tires, pollution of the air from fuel emissions, and untold numbers of organisms hit or run over by cars—for decades.

Wetlands are happy places because they provide space for so much biodiversity that the ground, air, and water cannot be anything but utterly alive. The loss of voices in wetlands is the loss of leopard frogs croaking and spring peepers chirping, the thready morse code of marsh wrens, the throaty roar of alligators during mating season, the whirring brittle sound of many species of dragonfly, with names like clubtails, darners, and red saddleback.

Yet these habitats also mitigate flooding, filter out human-made pollutants, provide buffers from storms, and are so essential to resiliency that when removed the state may, as in the Everglades, spend billions of dollars to restore the positive effects it once enjoyed for free.

In Florida, almost everything but uplands and rock pine habitat is some kind of wetlands, and subject to the rule and generosity of water.

The dismantling of wetlands is in a sense the dismantling of Florida itself.

In the human world, an inversion of success

If solid ground is an illusion in Florida, so too is the political landscape, especially for the average citizen. Neglect, greed, and business interests are regularly privileged, and sometimes even celebrated, over the rights of communities.

Under Scott and now in cascading ways under DeSantis, a host of preemption bills have stripped self-rule from local governments and made it easy to cut down trees, pollute, and subvert regulation. On May 24, DeSantis signed a bill, SB 540, overwhelmingly opposed by environmental groups, that makes it difficult for citizens to legally oppose changes to county comprehensive plans—often amended because of pressure from developers, now emboldened.

Samples calls it “a death knell” for smart growth in Florida that undermines resiliency and contradicts DeSantis’ own Executive Orders 19-12 and 23-06, 2019 Executive Order 23-06, which supported safeguards for responsible long-term planning. “Citizens were the last line of defense against unchecked sprawl,” says Samples, “and SB 540 has effectively stripped Floridians of our ability to challenge environmentally damaging, legally flawed projects that encroach on waterways, wetlands and green spaces.”

In June, DeSantis also signed into law SB 170, which allows businesses to sue local governments over so-called “arbitrary or unreasonable” laws, and SB 718, which prohibits voter referendums of ballot initiatives on land development regulation. Samples notes that these laws “defy logic,” in that “lawmakers in Tallahassee like to talk about the importance of ‘home rule’—then they undercut it year after year, to the detriment of our natural environment.”

It’s hard to ignore an investigative report published by the Daytona Beach News- Journal, that found 41% of state legislators have real estate ties—while these same lawmakers loudly proclaim that this fact has no effect on their votes.

Intensifying the potential damage, many special interests on the developer side are often companies that prefer to use prefabricated designs ill-suited for Florida’s unique topography. Decades ago, with better tree-protection ordinances, it was not out of the ordinary for a house in the capital city of Tallahassee to be carefully constructed around a massive live oak or even a mighty pine—with surrounding urban forest used as flooding and erosion mitigation. Yet now, new development tends to place expensive houses or apartment complexes cheek by jowl in ways that destroy biodiversity by cutting down most trees, removing the soil down to the clay, and filling in natural stormwater mitigation features in favor of holding ponds that do not effectively filter pollution.

Parts of Florida fade into invisibility every day, without being much chronicled, given over to a secret history of loss. Large patches of sky-blue lupine, a once common and dramatic sight in dry uplands, are disappearing due to development. Lupine often die if transplanted. Teams of volunteers rescuing native plants from future sites of clearcutting in Central Florida must leave these deep-rooted plants to their fate, sometimes lamenting as well the presence of gopher tortoises who also cannot flee, and sometimes end up being killed in the name of development.

Such places have intrinsic value and integrity. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), biodiversity annually contributes $125 to $140 trillion worldwide to economies and communities that extend to wildlife the basic right to life and land.

Florida does try to preserve wild places, if sometimes with one hand tied behind its back. Environmental nonprofits do heroic work under incredible pressures and the Florida Forever state program saves habitat and has played a role in the successful fight for 17.7 million acres for conservation in a much-lauded and valuable Florida Wildlife Corridor.

But the Act that established the corridor does not say wildlife and ecosystems have an intrinsic right to exist or inherent value—nor does it implement much in the way of legal protections. Instead, the Act uses vague language like “encourage” and “consider”—a stance that has practical impacts, magnified by the way DeSantis tends to reward his donors and supporters.

The corridor gives monetary incentives to large rural landowners, many of whom employ their own publicists to lobby for Corridor status. That includes Lykes Brothers, which owns vast tracts of ranch and agricultural land in Florida that stand to benefit—even as Mallory Lykes Dimmitt, Lykes Brothers’ former vice president of strategic development serves as head of the Corridor project. As early as 2003, Lykes Brothers received conservation easement benefits for Glades County property while retaining the right to use the land, to “drill for oil and gas, subdivide the area into 22 farms, [and] spray pesticides,” according to the Associated Press.

Recently, Lykes Brothers received Corridor conservation money from the state for 6,800-acres of company-owned land—even though 2,500 of those acres (roughly 25%) are being used for intensive agriculture in the form of eucalyptus and pine plantation and will remain Lykes Brothers property. This interpretation of “conservation” is, it seems, made possible by the Act’s vague wording. No studies have been done to determine how much other Corridor acreage may consist of similar parcels. (Lykes Brothers did not respond to TIME’s questions about the Corridor status of land owned by the company.)

Worse, a recent change to the legislation that determines how Wildlife Corridor status is granted means that landowners in the 75,000-acre southwest Florida Big Cypress conservation area will have a decade after their land is bought by the government to continue grazing cows, harvesting timber, and farming. On top of that, they will have the option to apply for two more five-year extensions. In other words, former owners could profit from the sale of their land at full market value—and then spend 20 more years profiting off the land before actually turning it over to conservation efforts.

This legislative loophole weakening the Wildlife Corridor joins another introduced in 2021 through the state budget that means owners of Corridor conservation land can receive additional money by having their wetlands serve as mitigation habitat for nearby wetlands destroyed by developers. Similar to disingenuous models of carbon offset, this means no actual additional conservation land is being set aside for the countless species that need it, from panthers and black bears to scrub jays and gopher tortoises.

Can wildlife afford to live in Florida? If wildlife can’t, how can we?

Greenwashing and ineffective policy

Much of the national environmental reporting on DeSantis has been “flat-out wrong,” according to Julie Hauserman, a long-time Florida journalist and activist. She says the media has been taken in by “greenwashing,” which leverages environmental concern to create the appearance of positive action.

“So many reporters wanted to hang the ‘Republican environmental’ label [on] him that was a fiction,” Hauserman says. “This take…surprised us all. His PR folks were relentless and very effective creating the narrative. You’ll see DeSantis in a windbreaker waving from a boat promising to save the environment and he gets on the local TV news. Most people don’t pay attention to the details.”

The governor’s version of greenwashing often takes on a particular form: money allocated, words spoken…and then results that may have little to do with either.

Consider DeSantis’ vaunted resilience program to protect Florida’s coast against sea level rise. In 2019, DeSantis hired Julia Nesheiwat as “Chief Resilience Officer” to head up that effort, but she left only six months later. “Florida needs a statewide strategy,” Nesheiwat concluded at the end of her tenure. “Communities are overwhelmed and need one place to turn for guidance.” The implication was that, despite the resiliency program, the “one place” does not exist, except, perhaps, in the governor’s office.

DeSantis wasted nearly two years before appointing a new, very experienced resiliency officer, Wesley Brooks, in December of 2021, but Floridians have heard almost nothing from him since. The rudderless policy on this issue continues, including a number of possibly counterproductive sea wall solutions for coastlines while efforts to enshrine effective natural solutions, like mangrove buffers, have died in legislative committee.

Kim Ross, executive director of ReThink Energy Florida, a nonprofit organization devoted to promoting clean energy, doubts funding put toward sea level rise is even enough. “And the longer this goes on, the more properties are impacted,” she says. “This impacts property values, which impacts the property taxes the counties and state have [to fund.]” It’s what she describes as “a cycle spiraling downward.”

Worse, the state fails to recognize the truth enshrined in its own Visit Florida tourism brochures: No matter where you go, “you’re never more than 60 miles from the nearest body of salt water.”

As Ross notes, sea walls will be inadequate because the king tides in southeast Florida “come in from the intercoastal waterways and the drains. So, the beaches are fine, but farther inland is flooded. Parts of our interior are going to impacted by sea level rise.”

One third of Florida properties live under threat of flooding of some kind, according to a CBS News report, with many residents lacking adequate insurance.

By June 9 of this year, Miami had spent 892.6 hours above mean high tide averages—over 100 hours more than during any other year on record.

On June 15 DeSantis vetoed millions in the 2023 budget for flood control in South and Central Florida.

Resiliency aside, DeSantis also hasn’t addressed Scott’s prior assault on Florida’s water quality. Today, the state has some of the most polluted lakes in the country. A 2022 investigation by the TC Palm revealed that DeSantis-era water policies are not working—and that many of the changes proposed by DeSantis in 2019 never actually happened. Even if, as Ross puts it, “Rick Scott set the bar really, really low,” the lack of results is hard to spin as sound environmental stewardship.

Every year, migrating white pelicans touch down in thousands of ponds in Florida, some meant to hold stormwater surge and (inadequately) protect against pollution. Every year, local newspapers report proudly on the grand spectacle of these large birds, but do not report on how rife with fertilizer and herbicide these waters may be, or that, in many cases, the same natural lake the pelicans once foraged in may now, as in the capital of Tallahassee, be treated as a dumping grounds for pollutants. This is the everyday reality in Florida.

DeSantis also has presided over a disastrous handover of control of federal wetlands in Florida from the federal government to the state. “Florida went from a highly regulated application process…to one managed by a short-staffed, underfunded, and untrained unit processing a record number of applications it cannot keep up with,” the Orlando Sentinel reported, underscoring the issue of staffing in program success.

Compounding the problem, water sources in Florida are so interconnected that the recent Supreme Court decision that weakened protections of certain kinds of wetlands under the Clean Water Act doesn’t just give a green light to further destroy these vital places. It may also provide cover or give an excuse for other types of environmental degradation, like those resulting from toxic fertilizer byproducts—an area where DeSantis’s record is particularly disastrous.

Run-off from phosphate-based fertilizer is a source of pollution that destroys ecosystems, including wetlands, and the food both people and wildlife depend on from those sources. Much of that destruction occurs because fertilizer feeds elevated levels of blue-green algae (freshwater) and the algae that causes red tide (saltwater). Both blue-green algae and red tide cause a host of health problems. This year, a red tide bloom encroached on South Florida that created breathing problems, rashes, and red eyes for humans—while marine life, including sea turtles, died off by the thousands.

Yet DeSantis is so committed to protecting the “lifecycle” of phosphate-to-fertilizer over water quality that this year he signed into a law a line item in the budget that makes it impossible for local governments to enact new bans or limits on fertilizer use, until completion of a study on fertilizer’s effects urged by fertilizer companies. He also signed a bill to research radioactive phosphate byproducts for use in building roads (currently banned by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). New research indicates that the DeSantis-approved release of 215 million gallons of contaminated wastewater from an abandoned phosphate mine into Tampa Bay in 2021—the “Piney Point Wastewater Disaster”—polluted the coast for miles and likely contributed to the intensity of red tide algae blooms in the region soon after the event.

Protecting business interests over human health also has had catastrophic impacts on attempts to reduce blue-green algae flowing south from Lake Okeechobee into the Everglades. In June of this year, the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science reported that more than 60% of Lake Okeechobee (some 448 square miles) was covered in algae blooms. Lake Okeechobee’s plight has also had a major detrimental impact on the formerly rich Indian River Lagoon ecosystems.

DeSantis created task force committees to address both types of algae, but to little effect. The governor has implemented only 13% of the recommendations from his blue-green algae task force. His red tide task force has reached the conclusion that red tide is bad and getting worse, but remained vague as to causes that would point toward the practices of industrial agriculture.

“So far, DeSantis’ tenure has looked different than Scott’s,” Samples says. “It’s about a lack of follow-through.”

Meanwhile, Florida’s canaries in the coal mine—manatees, the gentle herbivores of the river systems—are starving to death by the thousands, largely in the imperiled Indian River Lagoon area, due to the death of the staple of their diet, sea grasses, a symptom of the state’s environmental health. Few things in this world are more wholesome than a manatee and her calf floating effortlessly while grazing, yet this iconic symbol of Florida’s wildlife has been replaced by the image of the shrunken husks of the dead washed up on lifeless shores.

Various non-governmental organizations focus their attention on restoring sea grasses while the state ignores addressing root causes of the die-off, which include the same widespread water contamination that fuels red tide and blue-green algae blooms. Much of the sea grass being restored will die off again. Despite hundreds of properties around Lake Okeechobee violating state water pollution phosphorus limits, the state has imposed no penalties, the TCPalm found.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation continues to feed lettuce to manatees as a short-term solution. The FFWC website, perversely, continues to update the ever-lower population numbers while noting that the population “has grown.”

This is a dysfunctional human ecosystem.

Where we go from here

A regular visitor to the North Florida ravine on the Garden of Eden trail near the Apalachicola River might bear witness over time not just to the ebb and flow of decay and renewal over the seasons, but how the natural creek at the bottom protects against flooding during thunderstorms. How, during times of drought, that same creek still flows and the wooded slopes remain cool, shaded. The intricacy of how tiny iridescent sweat bees have evolved to extract pollen from swamp asters and other flowers is not arbitrary.

Nor is the feeling of rightness at the dry lurch and uplift of emerging on a path out of a ravine to the over-wheeling ache of blue sky across which glides a swallowtail kite, fresh off migration, looking down on gnarled pines, gopher tortoises, sudden sand dunes, and the entire landscape of Florida with razor-sharp vision.

Nor are any of these details trivial to human survival in an age of climate crisis. Bastions of complex life—in Florida or elsewhere—support all life; devaluing them or destroying them is, ultimately, like jettisoning the greenhouse gardens from a starship headed to Mars.

But a better future for Florida isn’t rocket science. It just requires wise governance that leads with actual science and best practices, while halting desecration of the state’s wild places. Resurrecting tools and processes that have been watered down or done away with over the past two Republican gubernatorial administrations would, in part, suffice, along with the vision and compassion to understand that communities deserve support, not corporations.

The other key is using the kinds of circular economy strategies being adopted by cities like Boulder, Colo. and Charlotte, N.C., applied at a state level. Organic “technology” like that used to create Sweetwater Wetlands Park in Gainesville, Fla., also could be applied by local municipalities, if true home rule is restored—and state-wide in robust and innovative ways. Doing so would not just stabilize biodiversity, but improve human quality of life and increase natural climate resiliency.

Looming over the hope inherent in simply implementing ready-made solutions is the threat of a DeSantis presidency. His slogan of “Make America Florida” contains the promise of environmental decisions based on pay-to-play, punishing perceived enemies, climate denialism, a reliance on fossil fuels, and a fundamental misunderstanding of core issues and their effect on the future.

DeSantis, at this point, registers on the horizon as a catastrophic climate event embodied absurdly in one person, affecting millions—and disastrous for both the economy and national security.

Florida can still be saved, but for this to happen, the state must save itself, or be saved, from this affliction.

No amount of money thrown at solutions can otherwise suffice.

Correction, July 20

The original version of this story misstated Mallory Likes Dimmitt’s relationship to Lykes Brothers. She is the company’s former vice president of strategic development, not its current one.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com