This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

Since Joe Biden raised his right hand and took his oath of office in January of 2021, there have been more than 1,600 mass shootings in this country. That was a relatively short 877 days ago.

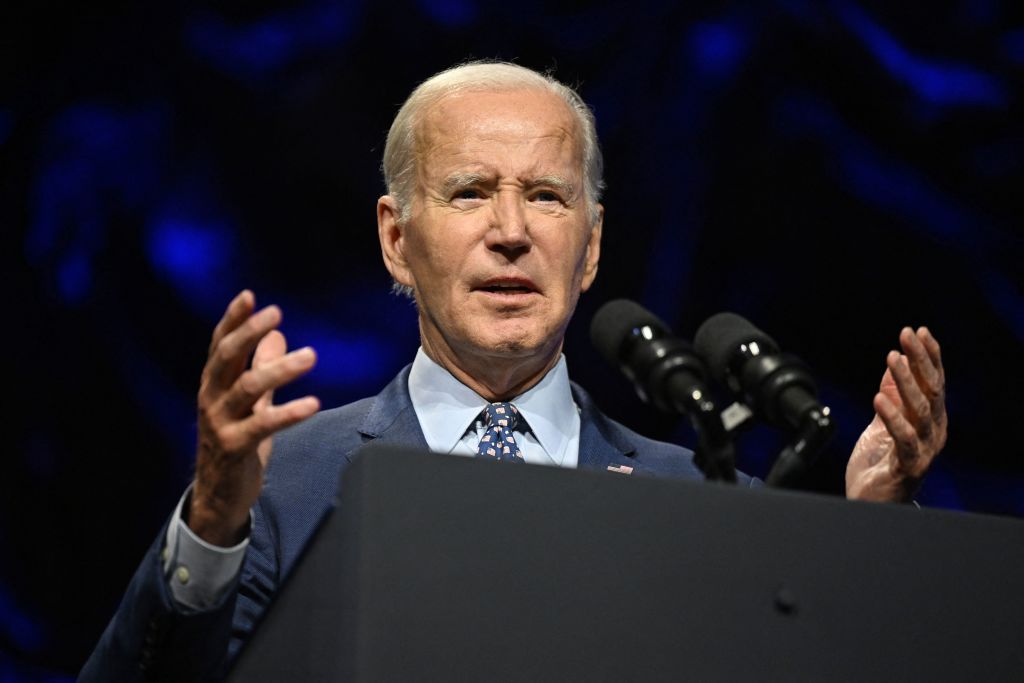

So, as the President joins fellow lawmakers, leaders, and wonks on Friday in Connecticut for an anti-gun-violence summit, a lot of Washington will be expecting Biden to offer more passionate rhetoric that will inevitably sprint headlong into an intractable wall of opposition from the gun lobby. Given the history here, optimism is in less supply than bullets.

Unless, of course, you’re Biden.

That there are so many mass shootings coming at such a rapid pace is a fact that has haunted Biden, and it goes back decades. In the Senate, Biden pushed tougher laws to boost safety, most notably a ban on assault weapons and a crime bill, both in 1994. The assault weapons ban lapsed in 2004 and lawmakers have lacked the votes for the last decade to bring back the measure that statistically saved hundreds of lives. As Vice President, Biden led the Obama Administration’s review of gun laws and restrictions, proposing technical fixes where he could to tighten up access to the deadly weapons. And as President, against stiff headwinds and long odds, he wrestled a once-in-a-generation package of gun limits into law and still wants to bring back the assault weapons ban despite almost impossible opposition.

Yet, when he talks about big wishes with his team, guns remain near the top of his to-do list. That unfinished idea is one that strikes at Biden’s always-raw emotion, and he has plausibly spent more time than any of his predecessors obsessing over what more the government can do to protect its citizens from gun violence. Almost certainly he has spent more time with gun violence victims than anyone who has reached the Oval Office. As a father who has buried two children, he has an instant and durable connection with the parents who have seen their children killed in school shootings.

Without a cooperative Congress, however, there’s really only so much Biden can do. He got Congress to budge on limited efforts, but his executive actions and orders have not been as sweeping as he had sought.

Anti-gun violence groups have long held Biden as an ally, but one who doesn’t warrant unlimited patience. Pressure has been building on the White House to take more concrete steps beyond their initial round of technical tweaks. Some of Biden’s most dogged advocates will be afoot, too, and listening closely to see what—if any—concrete steps the White House is teeing up.

On the other side, the gun lobby and its Republican allies in Congress have a tried-and-true playbook all but perfected: run out the clock after every one of these mass shootings and the intensity fades. With perhaps the lone exception of last year’s shooting in Uvalde, Texas, the violence’s urgency simply peters out, gun sales spike for fear of backlash, and lawmakers dust off talking points that have been useful for both sides since the Clinton years.

If it feels like a perpetual loop of calls to action alternating with calls for measured restraint, it’s because it is. Even as Biden’s aides on Thursday were finalizing his speech text, jurors in Pittsburgh were considering the case they had just heard about the 2018 mass shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue. Since then, there have been 2,949 mass shootings in the United States. Absent action in Washington, that number is almost certainly already outdated.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com