Chinese leader Xi Jinping, who turned 70 on June 15, has entered the second decade of his rule with unrivaled authority over China and his 97-million strong Communist Party. Xi can retain power indefinitely, having sidelined key rivals and discarded retirement norms during his first two terms in power. And his relative youth, considering that two of his predecessors lived into their nineties, suggests that Xi could still enjoy many more years at the top.

Much of Xi’s clout emanates from the illustrious image that he has cultivated for himself. Efforts to foster what some observers describe as a personality cult around Xi can be traced to his early days in power. In the spring of 2013, just months after Xi became the party’s general secretary, a group of prominent princelings—as descendants of senior party officials are known—and public intellectuals assembled at a Beijing hotel to celebrate the Lunar New Year. Among the attendees was Hu Dehua, a son of former party chief Hu Yaobang. While referring to Xi Jinping and other fellow princelings who grew up during the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, the younger Hu noted that many youth of that period had limited access to books and did little learning. That generation was now leading China, and “I just feel very worried,” he said.

Within weeks, Xi started raving about his passion for books. “I have many hobbies, the biggest of which is reading,” Xi told reporters, after name-checking eight Russian writers—including Chekhov, Dostoevsky, and Tolstoy—whose works he claimed to have read. Two months later, Xi charmed Greece’s prime minister by saying he read many works by Greek philosophers during his teenage years. When Xi visited France the following year, he boasted about reading Montesquieu, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Sartre, and more than a dozen other writers. State media feted Xi as an erudite leader, publishing lists of his favorite books and cajoling citizens to emulate his love for learning.

The publicity blitz set tongues wagging among princelings. Many concluded that Xi’s outlandish claims of literary prowess betrayed deep-seated insecurity about his lack of a formal education—particularly in contrast with Mao Zedong, who wrote poetry, and even Jiang Zemin, who spoke several languages and sang and played music alongside foreign leaders. “Xi is not cultured. He was basically just an elementary schooler,” one princeling who has known Xi for decades told me. “He’s very sensitive about that.”

Mythmaking is a key component of Xi’s push for preeminence. Whereas Mao and Deng Xiaoping won adulation through revolutionary exploits and epoch-defining achievements, Xi took power as a relative unknown and had to build his appeal from scratch. He opted for winning favor through populist deeds and folksy branding, drawing on imagery that recalls Mao and on methods that are more Madison Avenue.

The party humanized Xi with marketing on social media. A visit to a Beijing steamed bun shop in 2013 became a viral hit after fellow diners shared images of Xi queuing and paying for lunch. State media nudged netizens into addressing their leader as “Xi Dada,” using a colloquial term of endearment meaning “daddy” or “uncle.” Party-run studios created online videos to play up Xi’s credentials, including a 2013 effort—titled How Leaders Are Made—likening Xi’s ascent to the “training of a kung-fu master,” who proved his mettle by governing more than 150 million people over four decades as a local and regional official. Musical odes proliferated online, portraying Xi as a steely man of action, a loving husband, and even an ideal partner for marriage.

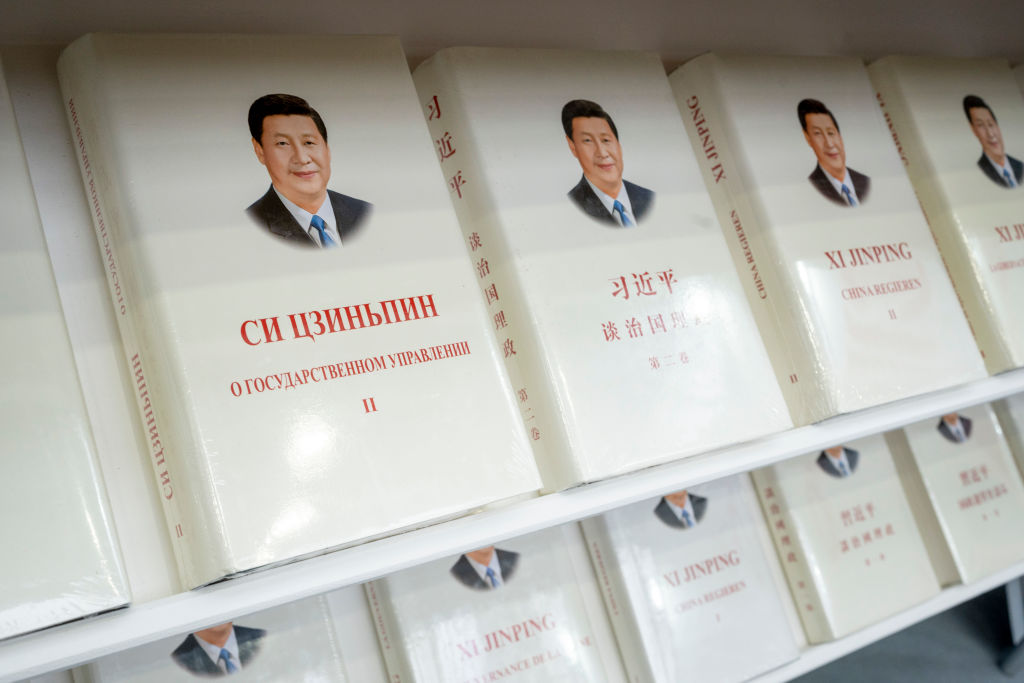

Xi also used traditional techniques more familiar to Leninists than millennials. State media plastered Xi’s name and image across front pages, websites, and television news bulletins. Party presses published hagiographic accounts of his life. Primary school textbooks describe “Grandpa Xi Jinping” as an avuncular leader who hoped to see China’s children become upstanding citizens. Xi accumulated titles of authority, becoming the party’s “core,” the military’s commander in chief, and the “people’s leader”—a designation that echoed Mao’s title of “Great Leader.” The party rewrote its charter to add an ideological slogan often shortened to “Xi Jinping Thought,” giving his words and ideas the power of holy writ. Media controls intensified as Xi insisted that all Chinese news organizations owed their loyalties to the party. Authorities ramped up internet controls, scrubbing anything that cast aspersions on the party and its leader.

The image-building stretched credulity at times. After a 2017 state television documentary aired old interview footage of Xi saying that he, as a rural laborer during the Cultural Revolution, would carry two hundred jin of wheat for ten li—roughly two hundred and twenty pounds over three miles—without switching shoulders, some netizens ridiculed what they saw as an implausible feat. Xi’s claims to be a sophisticated reader also drew scorn, given his repeated verbal slips in speeches—mispronouncing words and mixing up phrases—that critics attribute to his disrupted education.

Xi’s ubiquitous presence has unnerved many Chinese who see shades of a Mao-style dictatorship. But unlike Mao, Xi wants not mass participation but popular support—a source of political capital that he can use to overcome vested interests and bureaucratic inertia. And while Xi enjoys greater popularity than his predecessor, the enthusiasm for his leadership remains a pale shade of the mass veneration that Mao once commanded.

The party banned personality cults in 1982, and until Xi, its leaders seldom invoked the Great Helmsman beyond perfunctory references to “Mao Zedong Thought.” While officials insist that Xi isn’t resurrecting a Mao-style cult, the party has gone to great lengths to elevate Xi’s stature at the expense of Deng, the man credited for trying to inoculate China against one-man rule. Deng remained a towering figure well after his death in 1997, revered for enriching the nation and transitioning it toward a more stable leadership. This legacy supplies historical tradition and ideological authority that liberal-minded officials can cite to challenge Xi’s policies—a potent restraint that the current leader has sought to cast aside.

When the party celebrated the fortieth anniversary of Deng’s economic reforms in 2018, the fanfare focused primarily on Xi, even though Deng has long been exalted as the “chief architect” of “reform and opening up.” While Xi hasn’t tried to erase or repudiate Deng, the late leader’s supporters have been sensitive to any revisionist attempts to dilute his legacy.

Such contestation played out vividly in Shenzhen, where Deng is exalted for his role in transforming a sleepy seaside town into a high-tech metropolis. In December 2017, state-owned conglomerate China Merchants Group opened a museum in the city’s Shekou district—an early test bed for pro-business policies—to pay tribute to the politicians and entrepreneurs who had spearheaded “reform and opening up.” Deng was the most prominent figure featured. Visitors would encounter in the lobby a panoramic frieze depicting Deng’s 1984 visit to Shekou, a tribute that curators described as the museum’s centerpiece. Deng paraphernalia lined the route—photographs, quotations, calligraphy, as well as a chair that he once sat on. Nearly eighty thousand people visited the facility over the first six months, before it suddenly closed for “upgrading” in June 2018.

When it reopened two months later, the Shekou Museum of China’s Reform and Opening-Up was virtually unrecognizable. The Deng frieze was gone, replaced by two video screens showcasing local development and a beige wall adorned with a Xi quotation. While most Deng-related exhibits remained, the museum added a large volume of photographs, texts, and videos to extol Xi and his father’s roles in delivering prosperity to China.

A museum executive assured me that the redesign, which factored in public and professional feedback, “can stand the test of history.” But some visitors weren’t impressed. “They should respect history,” said a Shenzhen retiree who saw the museum before and after its revamp. “I feel that we’re reviving the cult of personality from Chairman Mao’s time. This is too dangerous.”

After I described the changes in a Wall Street Journal report in August 2018, overseas Chinese media lit up with discussions about what the pro-Xi revisionism suggested about political intrigue in Beijing. Weeks later, Deng’s eldest son gave a speech laced with oblique criticisms of Xi, particularly his assertive foreign policy. China “should keep a sober mind and know our own place,” Deng Pufang said, echoing his father’s famous calls for humble diplomacy. “We should neither be overbearing nor belittle ourselves.”

The shadowboxing between the Deng and Xi camps continued at the Shekou museum. Curators tweaked the lobby in September, adding a Deng quotation above Xi’s remarks on the wall and displaying Deng images on the video screens. Further renovations in October installed a new Deng frieze similar to the original sculpture torn down months earlier. Then in late December, the museum said it would be permanently closed to the public from Christmas Day—two days short of its first anniversary. “Now the exhibition’s mission has been fully accomplished,” a museum spokeswoman told me. “Therefore it is no longer open.”

Excerpt adapted from Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China’s Superpower Future, by Chun Han Wong

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com