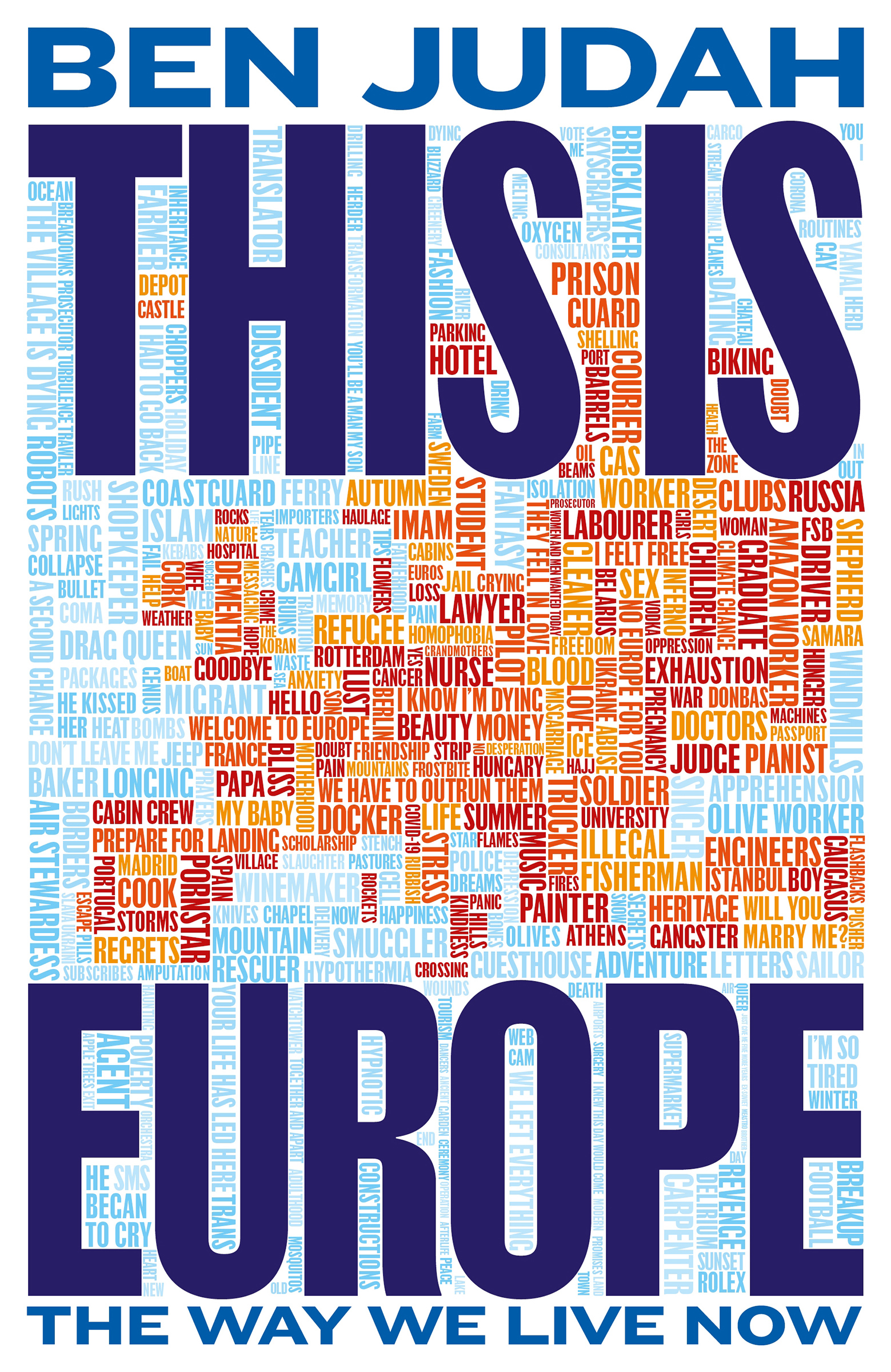

A Syrian refugee who reinvents himself as a porn star. A Spanish fisherman who joins an illegal fishing expedition to Antarctica. An Afghan Irani woman who gets trapped packing olives amid Greek wildfires. These are not the kinds of stories one might expect to hear reading about Europe or its roughly 750 million inhabitants. But in his new book This Is Europe: The Way We Live Now—which hits bookshelves on Thursday—British-French author Ben Judah makes the case that these stories are every bit as European as the quaint versions that live in the imagination of outsiders. They are the stories of Europe at its margins, on its frontlines, and within its ever-changing landscapes.

This isn’t necessarily the kind of book one might expect from a policy analyst such as Judah, who is the director of the Atlantic Council think tank’s Transform Europe Initiative. This Is Europe, which spans 2018 to 2023, is made up of vivid and empathetic portraits of those who Judah describes as “old and new Europeans.” In Col de l’Échelle, in the French Alps, we meet African asylum seekers traversing dangerous mountain routes in the hopes of finding a better life in Europe. In Homyel, in southeastern Belarus, we meet a local family that risks everything to protest against Europe’s last dictator. In Avdiivka, in Ukraine’s eastern Donetsk region, we meet a young woman who leaves her child to go cook for Ukrainian soldiers on the frontlines of war. Judah lets each of the 23 individuals featured in the book tell their own stories—a third-person, as-told-to style of writing.

“I wanted to gather all these people into this book and have each of them tell us a story about what Europe is today,” says Judah, “and to have each of them answer that question of what Europe is through their own lives.”

More from TIME

Speaking to TIME in London, Judah discusses how he found the people at the center of This Is Europe, the ways in which the continent has changed amid war, COVID-19, and climate change, and what it means to be European today.

TIME: How did the idea for This Is Europe come together? Did you envisage it as kind of a sequel to your previous book, This Is London?

Ben Judah: I initially wanted to write a book about France. I spent several months in France reporting and investigating, and I realized all the things that interested me—all of the themes about everyday life, about how the European cultural landscape was being transformed by migration, technology, climate change, supply chains, the knock-on effects from wars in Europe’s wider region—I couldn’t tell those stories in France. They were all continental stories.

Unlike This Is London, in which you served as a kind of narrator, This Is Europe is told from the vantage point of 23 people you interviewed. What influenced you to write the book in this way?

The moment when it really clicked for me that this was the book that I wanted to write about Europe, I was in Rotterdam. It was almost dawn and I was at a bus station. I looked around at all the people there and I thought about who they were, where they’ve come from, and where they were going in Rotterdam, which is really one of Europe’s great immigrant cities. And I thought, “Wow, these are really different lives. These are people living differently than the Rotterdam living 30, 50, let alone 100 years ago.” But how we think of ourselves as Europeans, let alone how Americans or Asians think of Europe, is still so clouded by these old sepia photographs and these old clichés and these clips from old movies.

I thought about the half-written book on France that I was lugging around and I opened it over the next few weeks and I thought, I hate this. I hate this narrator-centric way of traveling around Europe. It’s a piece of travel writing in which I meet people. Why is this interesting? I thought this was just totally the wrong way for people of my generation to be writing about Europe. There’s nothing interesting in my observations of Paris or my observations of Rome. They’re probably exactly the same as yours. All of us have seen all these places before, either literally or virtually through mass tourism or through Instagram.

I thought, I’ve got to break out of this paradigm.

I became a journalist because I love the experience of traveling around cities and continents and listening to people with very, very different points of view one after the other. So I wanted to write a book that had the closest possible feel to that—where you could read the book and you would meet, like me, one person after another from all over Europe telling their own stories in their own way and in their own voices. I don’t think there’s anything particularly special or interesting about the sort of “great white male wandering around” anymore. I think that’s a really outdated way of writing about things.

How did you decide which people to include in the book?

All of the people in the book are on this arc of life, from teenagers to people facing death. I decided that the selection would reflect Europe’s gender split, as close as possible to 50-50; that there would be stories of Europe’s sexual diversity that I felt had often been left out of how we write about the continent; and it will be the stories of new and old Europeans to give a sense of the complexity of European society today—both people who just arrived and people who felt their whole lives were deeply rooted in a particular place or even a particular profession.

There was one final thing, which is that everybody in the book is a storyteller. They all want to tell their stories and they all think that their stories say something profound and important about Europe today. And all of the stories add up to a question. All of the great political philosophies—liberalism, socialism, conservatism—they’re all about how we should live. What is a good life? And all of the people in the book are asking themselves, and they’re also asking you, is this the way we want to live now?

You spoke earlier about how those within and beyond the continent perceive Europe. How do you think This Is Europe will challenge, or enhance, those perceptions?

Europe is a lot of things. Europe is an idea. There’s a Europe of the mind made up of stained-glass windows and the smell of coffee and summer holidays, and I think that the Europe of the mind is growing increasingly distant from the Europe that we actually live in. I think the role of writers is to help people see and to help people feel. I wanted to help people see the real Europe. I think we live in a time and in a space and in a technological system that is pushing us all away from each other and into a situation where we know less and less and less about people who are outside of our own direct network.

As a European yourself, was there anything that surprised you in your reporting for this book?

People looking from the other side of the Atlantic think Europe is a staid, quaint, white Christian continent where very little happens apart from dusting in the museums. But actually, writing this book, I was really struck by the pace and intensity of the changes that are taking us far away from that.

One is the scale of immigration and how it’s experienced in all of Europe’s cities, in so many of its fields. I think that Europe is really blurring with Africa and Asia in all kinds of interesting and strange and unpredictable ways. One is how climate change is really changing Europe. The Europe that we have known and have been used to for millennia is disappearing in front of our eyes, and that really was driven home to me when I was in Burgundy. Like what could be more European than a glass of white Burgundy? I saw how the historic winemakers of Meursault are really struggling to keep up with the pace of change. And you can go to the churches there where the monks used to keep records of when the harvests—or the vendange as they’re called in French—would take place. And you can see that now they are weeks and even completely different months from when it traditionally took place.

And I felt that reporting in Greece, where I met refugees that had survived harrowing forest fires in the islands. I felt that interviewing somebody who was working in the north of Russia and he was telling me that the very pattern of the seasons and the ice are changing, and describing the mosquitoes and the dying reindeer herds in front of their eyes. It’s not the same Arctic, it’s not the same Burgundy, and that really shocked me as I went through this.

Every person in the book is trying to tell a story about how they feel Europe is dramatically changing. Life in Europe is changing more dramatically than it is in North America. The traditional ways of life in Europe are transforming faster, Europe’s cities are transforming faster. And the collision between these very old and rooted ways of life and the internet is producing really fascinating moments of friction, beauty, joy, and fear that I think Americans should pay attention to.

Do you think the subjects of your book identify as European?

The answer depends on whether or not they see their future in Europe. There are two really interesting cases there. We have Mahjoub, who was born in Tunisia but grows up in France outside Avignon, the old papal city, and he becomes an imam. He very much sees himself as a European. His future is in France and his children are in France. He is deeply involved in local politics and in local society and is trying to participate in these dialogues for community coexistence. Meanwhile, Abood, the [Syrian refugee and] Amazon delivery man in Berlin, I think if you asked him today he would say, “I don’t feel European. Me and my wife feel Middle Eastern, Arab, and part of a kind of Muslim civilization,” because he doesn’t want to see his future there. He’s actually dreaming of making it to Dubai and of going back to the region where his family are from, that he didn’t want to leave, because he feels it will be better for his wife.

The contrast there is about the future. What makes people feel European or what makes people feel British or Londoners, I think that it often is that question of the future and one thing that I found reporting this book and the previous book is that lots of immigrants have told me that they only started to feel British or French or European through their kids. That’s when you feel really settled and rooted, even if you always intended to go back; even if you always saw your own future elsewhere.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Yasmeen Serhan at yasmeen.serhan@time.com