Before Irvine, Calif. had its own mosque, Muslims would gather at Ali Malik’s home for nightly prayers during Ramadan. But after an FBI informant pretended to be a convert and spied on Malik’s lay congregation—and more than half a dozen Southern California mosques, as well, in the mid-2000s—trust within the community eroded. Malik’s family pulled back. The communal prayers came to an end. “We became closed off and afraid of reaching out,” he says.

Shocked by the experience, Malik and two other plaintiffs sued the FBI, accusing the agency of religious discrimination and unlawful government surveillance. But more than a decade later, the U.S. justice system is still wrestling with whether government secrecy trumps such claims of religious discrimination in domestic national security cases.

Malik’s case, FBI v. Fazaga, came before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit on Thursday. The government argues that all the plaintiffs’ claims alleging religious discrimination need to be dismissed because it has secret evidence that would exonerate the FBI if made public. “Since the court cannot hear evidence as to who the FBI investigated or why, it cannot adjudicate whether the government targeted Plaintiffs based on their religion,” the FBI has said, in legal filings.

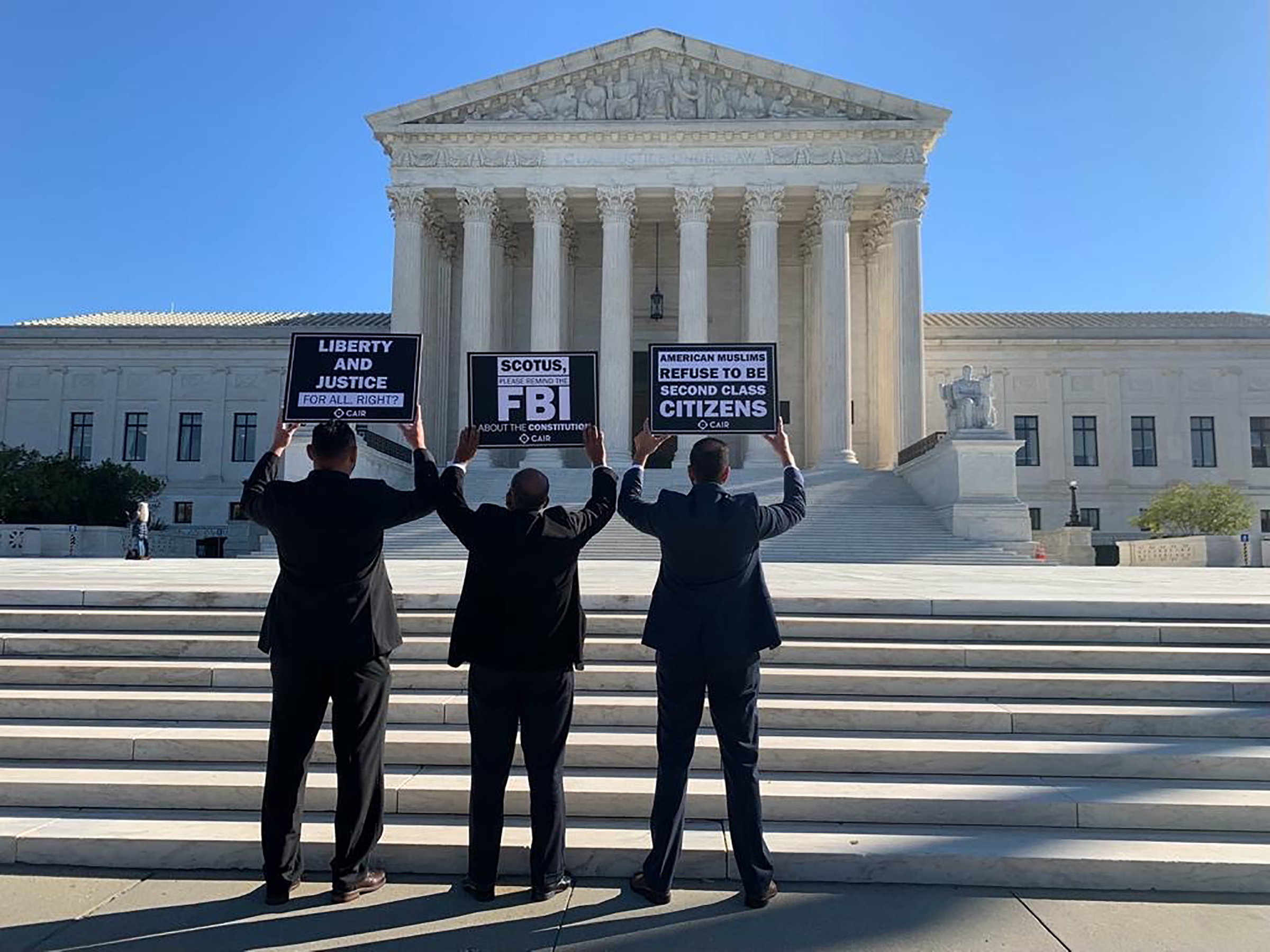

The plaintiffs argue that they don’t need secret evidence to win their argument and that the case should proceed without this information; the religious discrimination claims should not be entirely dismissed, they say. The government has so far not invoked the state secrets privilege for allegations of unlawful surveillance. The plaintiffs are represented by attorneys from the ACLU SoCal, the Center for Immigration Law and Policy at UCLA School of Law and the Council on American-Islamic Relations of Greater Los Angeles.

Mohammad Tajsar, senior staff attorney at ACLU SoCal, says that since 9/11, the government has repeatedly deployed the state secrets defense to kill cases. “It has basically prevented judicial oversight over a whole bunch of desperately abusive national security related policies—things like warrantless wiretapping and extrajudicial assassination,” he says.

Since 9/11, the government’s use of the state secrets privilege has increased dramatically. A 2008 congressional report found that the Bush administration raised the privilege in over 25% more cases per year than previous administrations had, and sought dismissal in over 90% more cases. “There are serious consequences for litigants and for the American public when the privilege is used to terminate litigation alleging serious Government misconduct,” the report stated. “For the aggrieved parties, it means that the courthouse doors are closed—forever—regardless of the severity of their injury.”

A more recent analysis in The Supreme Court Review by Laura Donohue, a professor of law and national security at the Georgetown University Law Center, says that over the past 15 years, the government has increasingly begun to assert the state secrets privilege in overly broad ways to cover entire categories of information. This happens even in cases when information poses no real risk to national security and is already in the public domain, she writes. This is a “radical departure from how the privilege has been understood for centuries,” she says.

The FBI declined to comment on the case and allegations that they were misusing the state-secrets privilege to avoid judicial oversight.

It’s a high bar to fight back against a state secrets defense, says Javed Ali, an associate professor of practice at Michigan University, who previously held senior roles at the FBI. Sometimes revealing classified information can cause unnecessary damage, he says: “There’s a tension in our legal system. That’s unfortunately why a lot of these cases are not successful.”

A lot of evidence about the FBI’s surveillance of Malik and his co-plaintiffs is already publicly available. Much of it details the activities of the pretend convert, a longtime informant for the bureau named Craig Monteilh and is drawn from Monteilh’s own sworn declarations, media reports and statements from FBI agents in other cases. Monteilh, who had served time for fraud, left his key fob and mobile phone in places to record conversations when he was not around. He recorded hundreds of hours of video inside mosques, homes and businesses. He told two other Muslims that “we should bomb something.” He says he was told by his FBI handlers to date Muslim women and have sex with them to get more information. The FBI dubbed the surveillance program “Operation Flex”—a nod to Monteilh’s strategy of using workout tips to befriend young Muslim men.

If the ACLU fails in its attempt to convince judges that the case should proceed without the secret information, they are arguing for at least judges to be able to review the evidence. “That way there’s some comfort that they are not just bullshitting us,” Tajsar says. If that doesn’t work, plaintiffs will fall back on a more procedural move—arguing that the government invoked the state secrets privilege too early.

Congress and the federal government have previously acknowledged concerns related to the overbroad use of the state secrets privilege. Lawmakers began drafting legislation in the mid-2000s to restrict its use but it failed to become law.

“There are a number of intermediate options between ‘the case can’t go forward’ and ‘everyone gets to see everything,’” says David Pozen, a law professor at Columbia University and expert on government secrecy. The federal bill would have made it so only the judge could see evidence in some cases; in others, the plaintiffs’ counsel could see the evidence with a security clearance and the requirement that they could not take it home.

The Obama Administration issued guidance in 2009 saying that it would “invoke the privilege in court only when genuine and significant harm to national defense or foreign relations is at stake and only to the extent necessary to safeguard those interests.” Last September, after a Supreme Court ruling in FBI v. Fazaga sent the case back to lower courts, Attorney General Merrick Garland, re-issued this same guidance.

In court Thursday, at least one of the sitting appellate judges expressed skepticism of the FBI’s defense after both sides made their arguments.

Peter Bibring, formerly senior counsel at the ACLU Foundation of Southern California, argued Thursday before judges that what FBI agents told the informant should not be considered a state secret—pointing out that the informant did not have security clearance and was hired based on his connections formed in prison. “The government cannot disclose information in that context to somebody like this in Orange County…and then turn around and say those are secrets that should justify throwing constitutional claims out of court.”

The FBI stood firm on their need for certain information to stay private. “There is no halfway solution. The state secrets privilege must prevail even if it means harsh medicine,” said Joseph Busa, a lawyer representing the FBI.

Judges probed the FBI for a “sensible solution.” “On the one hand the government should not be deprived of its defense; on the other hand, the plaintiffs should not be deprived of their case unless one really, really, really has to do that,” said Judge Marsha Berzon.

“The underlying problem here is that there is an inherent conflict of interest by the government: they’re both the defender and the protector of the interests and having no eyes on that is very troublesome,” Berzon said. “The notion that things are going to leak out that haven’t leaked out in the last 20 years is not very believable.”

Meanwhile, the plaintiffs’ and their Muslim communities in Southern California, remain shaken by the informant’s breach of trust.

Yassir Fazaga is an imam who used to work at a mosque in Mission Viejo, Calif., which Monteilh spied on, and another plaintiff in the case. Now, he abides by a strict rule: “If I cannot say it in public, I will not say it in private.” He’s no longer as welcoming with converts as he would like to have been. Sometimes he wishes that he were less visible. He does not even talk to his wife about the case because of the stress it has caused—even when it went up to the Supreme Court. “She did not hear it from me,” he says.

As for Malik, he has started talking about the case with his three young sons. “They want to be engaged and it’s forcing me to be engaged.” He recalls meeting Monteilh at the mosque and gym and wanting to be “as welcoming as possible.”

He doesn’t understand why they can’t litigate the religious discrimination claims in court. “What evidence did they have to come after me—and if it’s really that serious, how come nothing has happened? Why am I walking free?,” Malik says. “They were targeting me because of my religious activity, because I was a practicing Muslim in post 9/11 America.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com