The gender wage gap in the U.S. has remained stagnant over the past three decades. This statistic is surprising on its own, but even more so because the wage gap was narrowing in the 1980s. The reason for the stagnation remains a major puzzle in economics.

As labor economists studying inequality, we were drawn to the question of stagnant gender wage convergence. The answer that we found surprised us—the passage of family-leave policies such as the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) contributed to the stagnation of gender wage convergence. Our findings, released in a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper, underscore how difficult it is to make government policy aimed at reducing gender inequality without creating unintended consequences.

When President Clinton signed the FMLA into law in February 1993, he hailed the moment as a milestone. “Now millions of our people will no longer have to choose between their jobs and their families,” Clinton said. “This bill will strengthen our families, and I believe it will strengthen our businesses and our economy as well.”

More from TIME

The FMLA is a federal policy that requires firms to provide unpaid job-protected leave of up to 12 weeks for qualified workers, regardless of gender. The FMLA is often used following the birth or adoption of a child, for someone’s own medical needs, or the medical needs of a loved one.

Showing that the FMLA caused stagnation of the gender wage gap is difficult, however, because other federal policies that affect wages were passed around the same time. To overcome the confounding effects of laws coincident with the FMLA, we use the fact that in the 20 years preceding the FMLA (1972-1992), 12 states and the District of Columbia passed comparable job-protected unpaid family-leave policies. Using these 13 regional laws, we estimate that family-leave policies caused a 76% slowdown in the rate at which the gender wage gap was closing.

The policy rationale for family leave is clear: people should not be penalized for taking time away from work to take care of their families or themselves. However, if the intention of the leave is to prevent family obligations from negatively impacting someone’s career, our research sheds light on an unexpected consequence for women.

Read More: Men and Women Use Parental Leave Differently. They’re Judged Differently for It, Too

To illustrate our findings, imagine that women and men are playing a baseball game where the women start 9 runs down, but are reducing the score differential by 1 run per inning. Women stand a chance of tying the game in the 9th inning. Then, the umpire changes the rules in the middle of the game and women begin to reduce the score difference by 1 run every 4 innings. This is quantitatively what we find in the data before and after the passage of family-leave policies. Women’s wages were catching-up to those paid to men, but family-leave policies decelerated the convergence to a rate which is four-times slower than before the policy. Prior to the implementation of the FMLA, women in the U.S. were on track to attain gender wage parity with men as soon as 2017.

But why would gender-neutral family-leave policies affect the relative progress of women in the labor market?

In our study, we show that men and women differ in the length of job leave spells when the leave is due to the birth or adoption of a child. Women take approximately four times more days of leave, compared to men. Firms, engaging in a practice that economists refer to as statistical discrimination, may take the expected difference into consideration during the hiring or promotion process. For example, prior research by economist Mallika Thomas, of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, has shown that the FMLA lowered promotion rates for women by 8%.

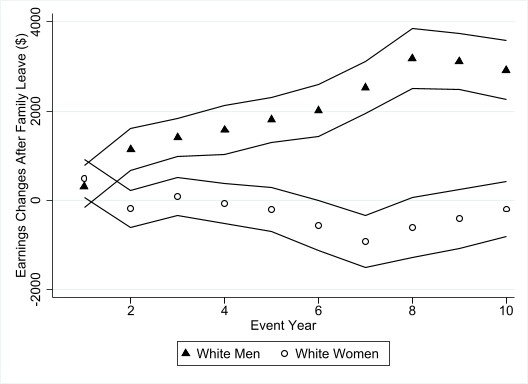

We find that the earnings gap between men and women widens after the implementation of the FMLA. For example, as shown in the accompanying figure, a white man who works 2,000 hours per year (40 hours per week with two weeks of vacation) has annual earnings which were almost $3,000 higher than expected 10 years after the policy. By contrast, white women’s annual earnings had declined by $197 following the policy, which is statistically insignificant.

Our study joins a growing body of empirical evidence by economists documenting instances in which gender-neutral family-leave policies have had unintended consequences. Research by economists Heather Antecol, Kelly Bedard, and Jenna Stearns measures that female assistant professors in top-50 economics departments were 17% less likely to earn tenure at their first academic job after the introduction of a gender-neutral family-leave policy. Conversely, tenure rates for their male counterparts went up by 19%. Moreover, work by fellow economic researchers Rita Ginja, Arizo Karimi, and Pengpeng Xiao showed that an extension of available paid family leave from 12 months to 15 months in Sweden increased the gender wage gap among workers in firms impacted by the mandate.

As more states move to augment the FMLA by mandating paid family leave (for example, the Illinois Senate Bill 208), it is even more important to perform research to fully understand the costs and benefits of family-leave policies passed to date. The work of UCLA economist Martha Bailey and coauthors offers an accounting of the benefits and costs due to California’s enactment of paid family leave in 2004. Their research found that new mothers were more likely to take leave, but 10 years later the women had 7% lower employment and 8% lower annual earnings.

We are not advocating for the repeal of family-leave policies. It is obvious that workers desire and value family leave. However, good policy must consider the benefits and the costs, particularly the unintended costs like the one we uncover in our research. Our work showing the impact of family-leave policies on stagnating gender wage convergence provides a resolution to an outstanding question in economics and highlights the difficult trade-offs that policy makers face in designing social policy to reduce gender wage inequality. Absent a change in gender norms around leave taking, policy makers should be more careful in the design and implementation of family-leave policies so that they do not have a disparate impact on women.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com