Roman Emperor Domitian is remembered for only one joke. “It’s a terrible thing to be an emperor,” Domitian said, “because everything thinks your paranoia about being assassinated is groundless—until you’re actually murdered!” Soon after Domitian was assassinated. Extreme vigilance is the essential mood of tyranny, which must inhabit that condition not just first because it is indeed in danger of overthrow and surrounded by enemies but also because it requires its people to be fearful and isolated, therefore conditioned for extreme solutions. President Vladimir Putin is living proof of this conundrum.

The recent drone attack on the Kremlin may have been the work of Ukrainian or internal Russian factions, possibly within his own wider security organs, or a ‘false flag’ operation by the regime itself, but it was inevitable that the dictatorship would claim it was an assassination attempt on Putin. This is absurd since everyone knows that the president does not live in the Kremlin but outside Moscow in his gilded mansion, Novo-Ogaryovo. Yet Domitian would sympathize because Putin has every reason to fear assassination.

It is a cliché of the cliché-ridden Western press on Putin—and his predecessors Stalin, Peter the Great, Ivan the Terrible—that they are paranoid to the extent of madness. It is a cliché that ignores and misunderstands the nature of dictatorship particularly in Russia. All absolute systems in world history depend on coercion to crush opposition and maintain power, thereby creating internal enemies who can only use violence to overthrow the ruler. All such systems deploy war and xenophobia to inspire and control their own people which creates another legion of enemies. The Western press always emphasizes the omnipotence of the autocrat in a system without limits without seeing that a system without limits means the leader exists in a permanent state of carnivorous chaos without any real or lasting security. Systems without clear rules of succession grant enormous power to the ruler but also mean they have no means of retirement. In Russia—whether under Tsars Ivan IV and Peter I , Stalin or Putin—rulers could appoint their successors but could never do so without creating a potential present menace.

In October 2011, during the Arab Spring revolutions, Putin spent hours watching the gruesome smartphone footage of longterm Russian ally, Colonel Gadaffi, who was sodomized with a bayonet before being shot. Putin resolved to save his ally, Bashar al-Assad in Syria. And himself. He no doubt reflected on the nature of Russian tsardom. He was aware of it from the start: when Yeltsin offered him the presidency in 1999, Putin hesitated, asking “how will I protect my family?” The answer? To establish a dictatorship and keep it for life.

More from TIME

Read More: Putin’s Path to War in Ukraine

Every wise tsar knows that his constant poise must be ferocious vigilance. Peter the Great set the standard of the all-talented emperor and supreme commander to which Putin—along with every other Russian ruler—aspires but he faced constant plots against his life which he handled himself by personally torturing and executing thousands of mutinous musketeers; he even tortured his own rebellions son Alexei to death. Peter invented modern Russia—even its name Roosiya was coined by him—as a new empire; he took the title imperator. The state has never developed from that vision. But this imperial self-image also sets a perilous standard for Peter’s admiring successors: the tsar – whether president or general-secretary—is also a military commander.

If a Russian ruler cannot dominate the “Russian world,” he will disappoint history. Peter was overwhelmingly successful in his wars—but even he was nearly captured and defeated by the Ottomans. Yet the dream of every Russian ruler is conquest. In 1904, Nicholas II’s Interior Minister V.K. Plehve, supposedly advised, “What this country needs is a short victorious war.” Every ruler (even in our democracies) aspires to one of those. Nicholas II instead faced a disastrous defeat vs Japan; but Putin built his imperial presidency and garnished his swaggersome overconfidence with a run of three ‘short victorious wars’ in Chechnya, Georgia and Syria. But they were minor skirmishes; Ukraine is proving very different…

Out of the last twelve Romanov emperors, six died violently. Ivan the Terrible and Stalin died in their beds by wreaking such havoc around them that no one dared destroy them. Putin is a killer but not yet a mass killer on their scale.

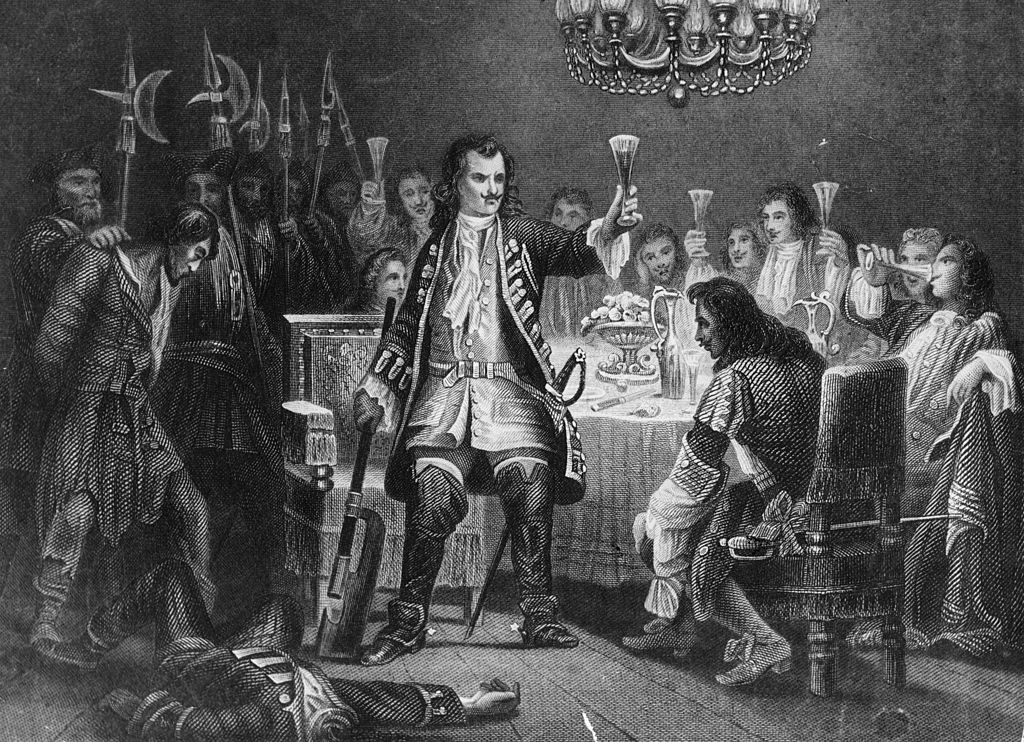

In June 1762, the new young Emperor Peter III—puny grandson of Great Peter—threw away costly Russian gains against Prussia. His own Guards and his wife Catherine the Great overthrew him; the Guards strangled him. The press release announced he had died of haemorrhoids. When Catherine later invited the French philosopher d’Alembert to Russia, he joked “I must decline because I suffer from haemorrhoids which are a fatal disease in Russia.” After midnight, on 11th March 1801, Russian Emperor, Paul, son of Catherine and Peter III, was awakened by footsteps on the stairs of his Mikhailovsky Castle; he hid behind a tapestry as the conspirators—slightly drunk after a pre-homicidal champagne—burst into his bedroom.

The conspirators were let in by trusted servant; they were led by his chief minister & top generals; and backed by his own son, who waited downstairs. What happened next was history’s most savage liquidation of a Russian autocrat.

Paul, inconsistent and menacing, was destroyed by war , capricious foreign policy—including sending an army to attack British India. The conspirators saw his feet peeping out of the wallhanging and dragged him out; conspirators hit him with a golden snuffbox, knocking out an eye, then threw themselves onto him, shattering his head on the floor, strangling him with his sash, then drunkenly stomping his head to pulp.

Just over a century later Nicholas II was not killed by his generals but he was overthrown by them. Yes the crisis was accelerated by hungry crowds in the capital Petrograd but contrary to popular history, he was forced to abdicate by his generals when he was isolated in his railway carriage on his way to put down the revolution.

Putin knows all this history. “How will history remember me?” he kept asking historians in recent years. His isolation during Covid made him one of history’s most dangerous creatures: the omnipotent history-buff. Stalin read history obsessively and collected a huge library—half of which is in Putin’s Kremlin office. Before the war, Putin liked to ask visitors to chose a book then together they would examine Stalin’s pungent marginalia. He is not an intellectual like Stalin but he reads historical biographies—including a famous Russian biography of Paul and my own biography of Catherine the Great and Potemkin. History matters to him; he has always been obsessed by eighteenth century Russian leaders, Peter, Catherine and Prince Potemkin. They were the trio who dominated Ukraine; all subsequent Russian-Soviet leaders including Lenin and Stalin regarded the possession of Ukraine as essential to their vision of Russian statehood.

It was Peter who founded St Petersburg and won the Baltic. It was Catherine in partnership with her brilliant lover, co-ruler and secret husband, Prince Potemkin, who conquered Crimea in 1783 and south Ukraine 1787-91, founding the cities Sebastopol, Odessa, Kherson that form today’s battlefield. When I wrote that first book in 2ooo, Putin, waiting for it to be translated, asked for a one-pager on Potemkin’s conquests and cities. In his speeches and essays before invading Ukraine, he cited Catherine and Potemkin. When his troops took Kherson, they captured Potemkin’s tomb and when they retreated late last year, they stole the Prince’s body. I predict that Putin will create a splendid tomb for Potemkin in Moscow to prove the Russian claim to Ukraine.

But the history also shows what happens when tsars fail. In 1964, Khrushchev was fortunate that he was only overthrown and retired after he risked nuclear war and delivered an unprecedented national humiliation in the Cuba Missile Crisis—though his successor Brezhnev did propose his assassination.

Victory makes a Russian ruler invulnerable, almost sacred. Defeat places a Russian ruler in danger from his closest courtiers, ministers and generals. While one thinks of tsars overthrown by crowds, most are actually destroyed by their closest colleagues deep within their own palaces. The modern prototype would be another secret-policeman-aspiring- to-rule, Lavrenti Beria, overthrown in June 1953 by his trusted, somewhat inferior comrades, Khrushchev and Malenkov (whose house at Novo-Ogorovo is now Putin’s home—what a small world) at a surprise meeting. He was shot.

When Russian leaders fall, nemesis usually comes from those closest. “When you walk down the corridors,” mused Stalin, “you never go when it’s going to come.” Putin is not paranoid; he has ever reason to be vigilant.

Domitian would sympathize.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com