This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

No serious player really wanted it, so a special counsel gets the tap on the shoulder. Mostly unlimited in scope, budget, and remit, the office has about as long a leash as exists in the current environment. Years upon years of work later, the project releases its final report. One side finds the results indisputably damning. The other insists the damning part is how little was found.

Washington has played out this routine on a loop. First came the release of the Mueller Report. Then, this week, the Durham Report. Each focused on different aspects of the Trump orbit’s interactions with Russia and the FBI investigation that followed. Mueller’s report yielded convictions, plea deals, and jail time, but nothing that stuck to Trump. Durham’s report yielded two acquittals, one plea deal, and a ton of second guessing. More than anything, both gave partisans fodder for hours of trolling. Taken together, they reveal how our self-perpetuating partisan outrage machinery makes it harder for Washington to get anything constructive done with the fruits of investigations that cost tens of millions of dollars.

Maybe it’s entirely our fault. We are a suppositioning sort. Where there are blanks, we fill them in, often in ways to match our existing biases. In fact, those vagaries allow many of us to arrive at book club meetings with very different interpretations of the same work based on the assumptions we brought to the plot and characters. The holes actually make for more compelling conversations than the agreed-upon facts.

More from TIME

It’s no different in politics, which relies on storytelling as much as policy. The gray area can sometimes be the most colorful.

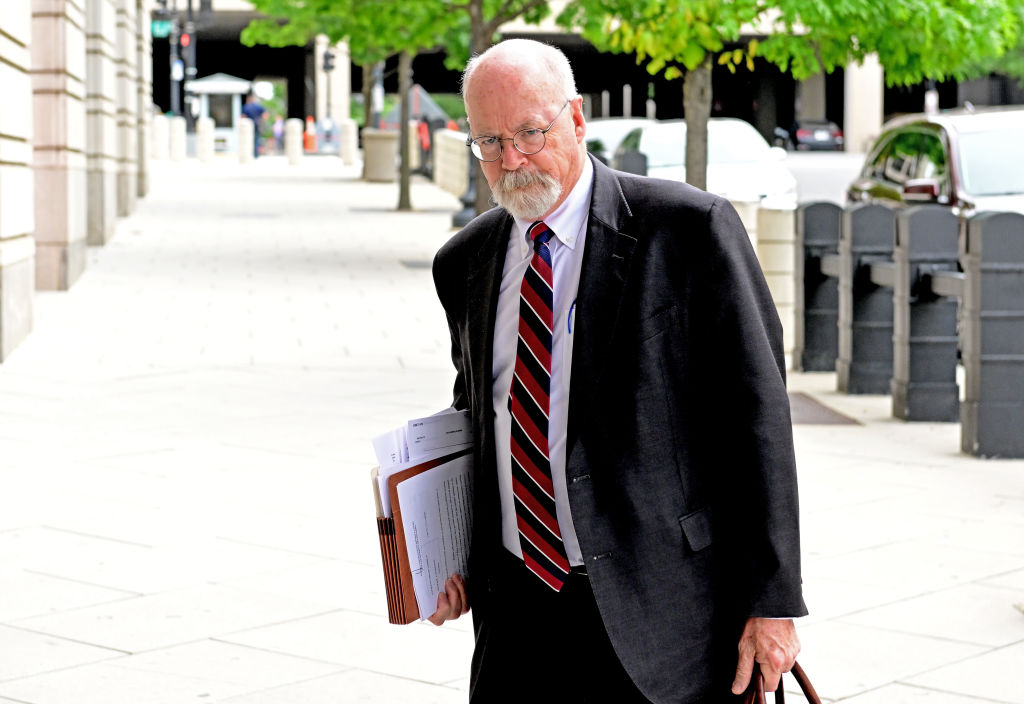

Special counsel John Durham, who then-Attorney General William Barr tapped to investigate those who had investigated his boss, released his much-awaited final report on Monday. Democrats largely shrugged off its 300 pages of findings as old news, recycled from reports from the Department of Justice inspectors general and three criminal cases that arose from the investigation. (Two of those cases ended in not guilty verdicts; a third defendant pleaded guilty to altering an email for a wiretap application.) Republicans, meanwhile, screamed bloody murder and political oppression so foul that one contender for the White House suggested it was time to dismantle the FBI.

The response has been an almost perfect reflection of the reaction to Robert Mueller’s two-volume report on the Trump campaign’s interactions with Russia. In that case, Democrats spotted sin after sin committed by Trump and his crew while Republicans brushed it off as fake news that was, at best, old. The facts were damning, the indictments seemingly self-writing, the consequences manifestly missing.

None of this is new, and little of it will be surprising for those who have watched special prosecutors wield almost unlimited power to produce lackluster results, time and time again. (Did we learn nothing from the Bill Clinton era?) But that doesn’t make the instinctive reaction to such findings any less a threat to society in which facts are ignored in service of a political agenda. While the timing was dodgy, the findings of the FBI’s probe of Hillary Clinton’s private email server were as clear as the Durham and Mueller probes—and carrying the same gaps that we tend to fill in with our own armchair indictments. Give us a gap, we will fill it with what we think we already know.

As Durham rightly notes early in his report, efforts to bring criminal charges against anyone based on his investigation would face an uphill trek: “The law does not always make a person’s bad judgment, even horribly bad judgment, standing alone, a crime,” he writes. (Emphasis added.) “Nor does the law criminalize all unseemly or unethical conduct that political campaigns might undertake for tactical advantage, absent a violation of a particular federal criminal statute. Finally, in almost all cases, the government is required to prove a person’s actual criminal intent—not mere negligence or recklessness—before that person’s fellow citizens can lawfully find him or her guilty of a crime.”

In other words, poor choices alone don’t automatically become legally criminal, no matter how much partisan outrage those choices may provoke. We can There Ought To Be a Law things to death, but absent a relevant law, sketchy decisions about doctored, damning, or deleted emails, often skirt by just fine. The wrongdoing can be spelled out as plainly as possible in these reports, but special counsels traditionally have been fairly unsatisfactory, especially when the missing pieces remain in desk drawers and off legislative calendars. It’s as if the expired law that made special counsels possible has rotted on the vine, and incompetence seems to breed plenty of reasons to think this is sadly normalizing.

So, as yet another special counsel has found, people—even smart people in powerful positions—make boneheaded decisions. Yet unless they’re explicitly against the law and the fool knows it, those actions don’t rise to the level of crime. Add in the question of conviction, and it’s terribly tough for these special counsels to yield anything approaching anything resembling consequences. Which is why, yet again, partisans will reach for the PDFs of these final reports and sketch their own indictments in the blank spaces. It is a Choose Your Own Adventure approach to political realities, one that may feel good to everyone involved but bad for the larger system, to boot.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com